- HOME

- /

- RD Classics

- /

The Remarkable Life and Work of Salim Ali

The story of the great scientist, who inspired three generations of Indian naturalists. From RD's November 1988 issue

Illustrations by Siddhant Jumde

Illustrations by Siddhant Jumde

I watched the heaving monsoon seas, with a sinking heart. Being tossed about in a narrow dug-out canoe was not something I’d bargained for when I joined the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), a few months earlier. As one of my legs began to twitch uncontrollably, the tiny bearded man sitting next to me asked, “Can you swim Daniel?”

“Swim? Y-yes,” I stammered wondering wildly if Salim Ali, the legendary honorary secretary of the BNHS was about to give the order to abandon ship. Instead, Salim Ali looked at me for a moment and said quietly, “I can’t.”

His calm words immediately banished much of my fear, and from then on, I learnt not only to cope with harsh surroundings, but to savour every minute, as a true naturalist should.

That was the kind of effect Salim Moizuddin Abdul Ali had on you. To the world he was amazingly versatile—ornithologist, explorer, ecologist, teacher, writer. But to all of us at the BNHS with which he was associated for 80 of his 91 years, this bright-eyed, sparrow-like figure was an all-knowing father, the person we refer to as the Old Man. And, like a father, he dazzled us with his achievements.

Taking up ornithology at a time when the subject in India was little more than an Englishman’s pastime, Salim Ali made it a serious pursuit. He studied the birds of nearly every region of the subcontinent and wrote with such wit and elegance that he was included in an anthology entitled Indian Masters of English, along with Rabindranath Tagore and Sarojini Naidu. His many awards included the Padma Vibhushan, and three honorary doctorates. He was nominated to Parliament and made a national professor. Under him, the BNHS became a premier research centre, and its Journal, a staple for biologists the world over.

Born in 1896 into a prosperous close-knit Bombay family, Salim Ali, the youngest of 10 children, was orphaned early. His childhood hero was his flamboyant uncle Amiruddin Tyabji, a sportsman who joined royalty on grand shikars. When Salim was 10, Uncle Amiruddin presented him with a Daisy air gun. One day, young Salim shot a strange-looking sparrow. When his uncle couldn’t explain why it had a yellow streak below its neck, he suggested that Salim take the bird to the BNHS. There, the secretary, an Englishman, identified it as a yellow-throated sparrow, and showed the boy the society’s vast stuffed-bird collection. Awestruck, Salim Ali remained hooked on birds, and the BNHS, for life.

In between visits to the society, Salim Ali scraped through high school. College, though, proved too difficult and, “escaping from logarithms and higher algebra”, he sailed to Burma and spent the next 10 years there as a partner in his brother’s timber and wolfram business. But when Salim Ali was sent into remote jungles to select timber, he’d spent most of his time, observing birds and wildlife. Not surprisingly, the business collapsed, and, owing a lot of money, he had to return to Bombay with Tehmina, his wife of six years.

He got a job as a guide–lecturer at Bombay’s Prince of Wales Museum in 1927, but after two years decided to study ornithology at the Berlin University Zoological Museum under Professor Erwin Stresemann. When Salim Ali returned to Bombay a year later, he discovered that his guide–lecturer’s post had been abolished. There was no chance of working for the government, either—a couple of years earlier he’d been rejected for an ornithologist’s job because he didn’t have a college degree.

In those days, anybody with his energy and command of English could easily have found a comfortable niche in a Bombay firm, but Salim Ali didn’t even bother to apply. His family thought him mad—an unemployed, married man cheerfully content to watch birds all the time!

Tehmina, though, stood by him. A warm, lively woman, she came from an affluent family and was educated at a finishing school in England. But she was a country girl at heart and shared many of her husband’s interests. “Finishing school,” Salim Ali once wryly remarked, “did not finish her.” Tehmina’s family owned a small cottage in Kihim, a coastal village south of Bombay, and the young couple moved there. Kihim was green and full of birds to keep Salim Ali forever busy. “Don’t take a job,” Tehmina told him. “if you can’t enjoy it.” Salim Ali never did.

In 1930, Salim Ali went to the BNHS with a proposal. Indian birds have not been studied systematically, so would the society send him on ornithological surveys? He didn’t want a salary, only expenses. Thus, for the next 20 years Salim Ali roamed the subcontinent, studying birds from Kutch to Sikkim, from Afghanistan to Kerala.

His methods were so unique—he wove history, ecology and geography into his description of a bird, and its habitat—that in 1936 he got a letter from Ernst Mayr, a leading American biologist who was a bird curator at New York’s Museum of Natural History. “Congratulations,” write Mayr, who’d been following Salim Ali’s reports in the BNHS Journal. “I hope your work will set a standard for similar surveys.”

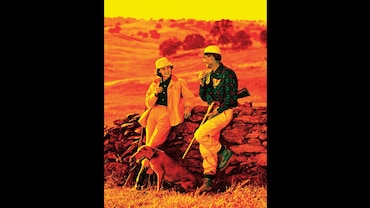

Salim Ali (second from the left) with Mary Livingston Ripley and S. Dillon Ripley on a 1976 research expedition for the Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan.

Salim Ali (second from the left) with Mary Livingston Ripley and S. Dillon Ripley on a 1976 research expedition for the Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan.

For Salim Ali, these two decades were a time of both achievement and sorrow. In 1939, Tehmina, who accompanied him on all his exit expeditions, died suddenly after a minor surgery. For months, he was rudderless, and stayed with his sister in Bombay. True consolation came only when he resumed work.

In 1941, Salim Ali published The Book of Indian Birds. It was an instant success, and its royalties enabled Salim Ali to repay his old business debts. Jawaharlal Nehru read it and liked it so much that he sent it as a birthday present to his daughter. “It opened my eyes to a new world,” Indira said years later. “For the first time. I paid attention to bird songs, and was able to identify the birds.”

During this period, Salim Ali also made innumerable friends, like S. Dillon Ripley, a young zoologist with the US Army in Ceylon, who later became secretary of Washington’s Smithsonian Institution. Pooling their wide knowledge, the two men would later published the 10-volume Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan.

By the time I became BNHS curator in 1960, the man who once had been rejected for a government job for a want of a degree, was guiding PhD scholars. I watched him work amid stuffed birds and neatly arranged piles of books and paper. He was so precise that when I had an appointment with him, I made sure I arrived early. When any visitor’s business was over, Salim Ali would raise his grey eyebrows and pat the arms of his chair. If that failed, he’d politely say goodbye and resume his tasks.

Bad work maddened him—his face would redden, and his head would shake. One look at a shoddy report and he’d fling it aside, storming furiously. “Silly” was his strongest form of abuse, but he had such a way of delivering it, you’d never want to hear the word again. Once Venugopal, a BNHS clerk forgot to post a letter Salim Ali had given him two days earlier. “Silly fellow,” Salim Ali yelled when he found out, and grabbing a bottle of ink, emptied it over Venugopal’s head. But his anger always disappeared quickly. Venugopal for instance was an avid stamp collector and Salim Ali, who got letters from all over the world, used to give him the stamps. After the ink shower, Venugopal went home. But when he returned, Salim Ali apologized and gave him another set of stamps.

Nothing escaped Salim Ali’s notice and he took a personal interest in each of us. BNHS naturalists on field trips had to write to Salim Ali every week. “He’d reply promptly,” recalls V. C Ambedkar, Salim Ali’s first student. “And he wouldn’t just comment on my bird observations. He’d emphasize the importance of punctuality, hard work and correct English.” In 1962, when Ambedkar was on assignment in the tiger-infested forests of Kumaon terai, Salim Ali visited his student’s anxious mother. “I’ve informed her that you have not yet been eaten by a tiger,” he wrote to Ambedkar, adding with his characteristic dry wit, “She appeared pleased.”

Writing letters, in fact, was another of his great enthusiasms. He spent large sums on postage out of his own pocket, keeping in constant touch with friends or voicing his deep concern for the environment. The setting up of Bharatpur and Karnala bird sanctuaries, the decision to not destroy Kerala’s Silent Valley for the sake of a power project and many other similar measures were due in large part to the Old Man’s powerful letters to prime ministers and forest officials. But his mail wasn’t always addressed to the high and mighty. He even wrote to poor villagers he’d met during his expeditions, though he knew they were illiterate and couldn’t reply.

When in Bombay, Salim Ali had a strict routine. Up by five, he’d take a walk, then work for a couple of hours before leaving for the BNHS. Every morning at precisely 9:45 I’d hear his motorbike outside the office. Although he worked long hours, he was in bed by 10 p.m. “Like the birds,” he’d say, “I prefer to work by day.” He ate like a bird, too, enjoying good food, but consuming very little—a bit of curry and often just one chapatti. These austere food habits sometimes troubled me while on field trips with the Old Man. I’d be too embarrassed to eat more than three chapattis, so I survived by getting friendly with the cook and eating one dinner in the kitchen and another with Salim Ali.

Others, too, had problems. Knowing his pet aversions, nobody dared smoke or drink in his presence. Travelling with him, you often saw a small group desperately puffing away during breaks. And above all Salim Ali hated snorers. To share a camp room with him, you had to be a proven non-snorer. Once the Madras government provided him with a camp guard who snored. Salim Ali sent him packing.

Because Salim Ali’s needs were few, he had hardly any use for money. His writings and awards brought him large amounts, but he kept very little for himself, liberally handing out scholarships and grants to needy students. He donated his 1976 Paul Getty Wildlife Conservation Prize, worth $50,000 [roughly INR 8.4 crores today], to conservation—research fund at the BNHS. Even in the days when he worked on shoestring grants, there’d be money left after project. “Don’t spend without purpose,” he often told me. “You’re accountable not just to the BNHS but to yourself.” He avoided buying new things, preferring to maintain his knife, gun, binoculars, car or motorbike in mint condition.

He had a teenager’s fascination for motorbikes which he loved to tinker with and drive at breakneck speed. In 1950, he shipped his massive Sunbeam 500cc bike to Sweden, and, luggage strapped behind, rode into an ornithological conference, startling the other delegates, who’d assumed he’d ridden all the way from India. After the conference, he rode through Europe, making friends—human and avian. In France, he was injured in a collision with a speeding truck, but the next morning, Salim Ali got out of his hospital bed and repaired the bike himself. Head bandaged, he kept a lunch appointment later that day.

Nothing could dampen Salim Ali’s spirit, not even old age. Until his 87th year, he conducted major expeditions, and, in 1983, spent four weeks in the remote and difficult Namdapha National Park, near the Burmese border. Two years later, he was set to go to the Himalayas in search of the mountain quail, last seen in 1858. But he suddenly fell ill and we all persuaded him to stay. He used the time to finish one more book, The Fall of a Sparrow, his delightful autobiography.

One of Salim Ali’s last wishes was to set up an ornithological Institute in Bombay. In April 1987—after his illness had been diagnosed as cancer—he flew to Delhi to attend a seminar to convince Rajiv Gandhi about the need for the institute. Hospitalized as soon as he arrived, he kept insisting on going to the seminar, until the Prime Minister visited him and assured full support. Two months later Salim Ali died, probably the only thing he ever did without his heart in it. For despite all he’d done, he felt there was much more left. “I’m not ready to die,” he used to tell me. “I’ve only touched the surface.”