- HOME

- /

- RD Classics

- /

A Lesson in Diplomacy From Dag Hammarskjöld

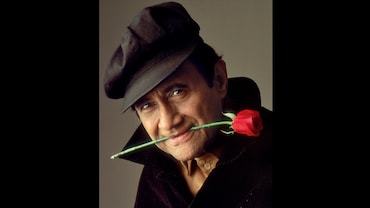

Words of wisdom from the Swedish economist, former secretary-general of the UN and Nobel Peace Prize recipient

Alamy

Alamy

It happened really, in three acts. Maybe that’s the way I should try to tell you about my experience, two years ago, with the late Dag Hammarskjöld, and my ancient jeep.

Act I

I was preparing an article about international negotiations and had an appointment with the Secretary-General of the United Nations late one afternoon in his office on the 38th floor of the UN Secretariat building. Seasoned diplomatic reporters warned me that my quarry was shy, reticent and rather formal—a difficult subject.

To my surprise, he greeted me in shirtsleeves, smoking a pipe instead of his usual small cigar. As he rose to shake my hand, I saw that he was taller, thinner and blonder than he appeared on television.

He motioned me to a table at one end of the room, and we went quickly to the subject at hand. In answer to my questions, he spoke with force and conviction about the importance of the United Nations, what it had already accomplished and what he hoped for its future.

“Let us not make the mistake,” he said, “of undervaluing the mediation and conciliation that go on here among nations every day. In some small way injured pride is comforted, anger is harmlessly vented, conflict ends in compromise.” As our discussion drew to a close, the telephone rang. From the conversation I gathered that a man with whom Hammarskjöld had planned to have dinner had been taken ill. He looked disappointed. Amazed at my temerity, I blurted, “I’d be honoured if you’d have dinner with me.”

I expected the Secretary-General to refuse. Instead, he said heartily, “Fine idea!”

As we walked down the hall, I told him that I lived in a Connecticut town 95 km from New York, that I had missed my train that morning and had driven to the city in our old red jeep. “A red jeep!” he said. “Imagine!”

Racking my brain for a restaurant to suggest for dinner, I started to describe a small place I had recently discovered in uptown Manhattan where excellent Creole food was served. “Ah, Creole!” he exclaimed. “Shrimp and rice. Let's go there. I have dismissed my chauffeur, but we can ride in your red jeep.” “It’s completely disreputable,” I spluttered. “The side curtains are off, and it bucks in low gear and ...”Hammarskjöld, with a twinkle in his pale blue eyes, put a hand on my shoulder. “Courage!” he said.

Act II

As we chugged uptown in rush hour traffic, a horn blasted sharply at me from behind. Then a taxi shot past me on the left and, suddenly, cut to the right across my bow. I leaned on my horn, jammed on the brakes, twisted my wheel to the right—and ran upon the sidewalk. Sideswiping a metal waste container, which clanged like Big Ben, the jeep carrying the Secretary General of the United Nations—and me—came to rest against a lamppost.

Incredibly, no damage was done. The taxi came to a halt, and its driver started striding towards me. Before he reached me, I snapped at him, “Why didn't you signal? Couldn’t you see you were cutting me off? What kind of a fool driver are you?”

The cabby bellowed, “What do you mean by all that blasted honking? What’s the matter, you blind or something? Where’s your brains?”

He demanded to see my licence. I showed it to him, and demanded to see his. He snorted, “These days they give licences to everybody. Even guys like you!” My embarrassment turned to rage. “You could have killed us all, you maniac!” I shouted. Now both of us had retreated to extreme positions. I could see the cabby's muscles tensing. I planted my feet firmly on the pavement. A crowd had begun to gather. The taxi driver turned his back on me and began to talk to Hammarskjöld. “If I was you, I wouldn’t ride with this guy,” he said contemptuously. “He’s just a country driver—him and that jeep shoulda stayed in the sticks where they belong.”

I was about to make an indignant reply when Hammarskjöld said quietly, “It must be tough driving a cab all day every day in this town. I’m glad I don’t have to do it—I couldn’t stand it. I'm surprised there aren’t more accidents!”

I could see that the cab driver was taken aback. Here was someone talking to him sympathetically. “Yeah,” he said, “it is tough. If it isn’t the other drivers, it’s the snow or the rain or the cops or the trucks. You can’t win. It’s always tough driving in this town!”

I had been ready to continue the argument, but now, perhaps, I could back off a little, too. “It sure is tough,” I said feelingly. “I’m glad I don’t have to drive here more than a couple of times a month.” Hammarskjöld murmured in my direction, “I’m sure your job has its hazards, too.”

“I guess I was rattled, having you in the jeep, sir,” I said. “Maybe I was a little careless.” Hammarskjöld turned to the taxi driver. “My friend feels he may have been a little careless.”

“Aw, maybe I did crowd him,” the cabby admitted. “I suppose I should have realized he was an out-of-state driver. He probably don’t understand New York signals.”

I was about to tell him I had been born and brought up in New York City and had held a driver’s licence therefor 15 years. But it suddenly dawned on me that Dag Hammarskjöld, in order to calm down two near belligerents in a minor traffic incident, was using the arbitration formula for international negotiations he had described to me earlier!

“The arbitrator must always keep three things in mind,” he had said in his precise way. “One: Do not be dismayed if a situation seems irreconcilable. After all, if both sides aren’t shouting dangerous threats at each other, the arbitrator is not needed. The important first step is to establish sympathetic relations with both parties and to remain in contact while the initial sword rattling goes on.”

“Two: Try to persuade the angry parties to vent a sizable portion of their anger on some impersonal, abstract target. Different shades of meaning in language, the inescapable pressures of economics or even the psychological effect of climatic conditions can be used to ‘air-condition’ a serious quarrel.”

“Three: Find some area of mutual concern that will draw both parties into a positive discussion. It may be utterly irrelevant to the problem at hand, but once you get them to say something like, ‘There’s a grain of truth in that’, there is an excellent chance that a harmonious solution may ultimately be reached.”

“It’s amazing,” he had concluded, “but history shows that two countries which have been persuaded to retreat from the verge of war can often become good friends, even help one another.”

Gradually, remembering these things, I stopped scowling. The cabby’s bluster ebbed, too. “I guess we both got to watch out a little sharper,” he said. I nodded. He retreated to his cab. Apologizing profusely to Hammarskjöld, I backed off the curb and we started uptown again.

Act III

About 10 blocks later the jeep’s engine sputtered. I glanced at my gas gauge. The needle pointed to EMPTY.

“Boy, this is it!” I said miserably, forgetting diplomatic language. “I've really messed things up!” I coasted to the curb, yanked on the hand-brake and suggested that we go to the restaurant by taxi. Just as I yelled, “Taxi!” a cab pulled up.

It was the same driver with whom we’d had the run-in a few minutes earlier.“ You guys in trouble again?” he asked. “Out of gas,” I said glumly.

“ Hop in ,” he said .“There’s a gas station up ahead.” Hammarskjöld elected to stay with the jeep. As we drove along, the cabby said, “That’s a nice guy you got riding with you. A quiet fellow, but real nice.”

At the gas station, he waited while I bought a canful of fuel, then drove me back to my stalled car. I reached for my wallet, but I saw that the metal lever on his meter was still up—the fare had not been registered.

“It’s on me,” he said. “Forget it!” Waving cheerfully, he drove away.

In the light of all that has happened since, I suppose that this ride with Dag Hammarskjöld may not have been world-shakingly significant. I find myself thinking about it surprisingly often, however. Maybe you will, too.