- HOME

- /

- RD Classics

- /

Forever Dev

An RD interview from our September 2003 edition with the Bollywood legend we lost a decade ago this year

Bandeep Singh

Bandeep Singh

As the young woman lay dying, she called out to her husband and one of her sons. Holding the boy’s hand, she gazed into his eyes and told her husband, “One day, this son of mine will become a very important man.”

With such expectations to live up to, it was no wonder that 19-year-old Dharamdev Pishorimal Anand vetoed his father’s advice to find a secure job in the local bank. Convinced that fame and fortune awaited him in the movies, the young graduate left Gurdaspur, Punjab for Bombay, with just INR 30 in his pocket.

It was 1943, the height of World War II, and times were tough. But in less than three years he got his break as an actor, and went on to become Bollywood’s most durable leading man—Dev Anand. His trademark screen persona of the charming, urbane rake endeared him to millions. And his unique mannerisms—a loose-limbed gait, tilted head, index finger pointed up—was imitated throughout the country.

Today, having starred in or directed more than 100 movies in the span of nearly six decades, Dev Anand, often works 17-hour days, his head teeming with ideas for films. We met Dev Anand in his spacious suburban Mumbai office overflowing with scripts, files, books, magazines, cinema posters and snapshots of aspiring starlets.

RD: What still motivates you at age 80?

Dev Anand: The sheer excitement of my work. Age has nothing to do with it. I’m writing my autobiography. And I’m working on my next film Song of Life. It’s in English, and I play an Indian musician who discovers he has a gifted daughter from an old affair with an American woman.

RD: Is it about Ravi Shankar and singer Norah Jones?

Dev Anand: No, it’s fictional, but I got the idea in a flash while I watched Norah Jones on TV, winning five Grammys. I was in New York, packing to return home, but I was so inspired that I postponed my departure, stayed put at my hotel for a month, and wrote the entire script.

RD: Like a journalist, you react to events.

Dev Anand: I see cinema in incidents. My first directorial venture Prem Pujari was sparked by the 1965 Indo–Pak conflict. Then, in 1970, I was visiting a place called The Bakery, a hippie hang out in Kathmandu. And there was this, brown-skinned girl swaying in the lap of a dirty, bearded, bespectacled foreigner. What’s a nice Indian girl doing here? I wondered. That girl inspired Hare Rama Hare Krishna and Zeenat Aman played her in the film. I made Censor after an unpleasant experience with our Film Censor Board

RD: But many of your recent films haven’t succeeded.

Dev Anand: They’re good films, but not all good films are successful. Some outstanding ones flop, and some average ones become hits. What makes a film a box office hit? It touches a chord in people and they want to see the film again and again. Precisely what touches this chord? Nobody knows beforehand.

RD: So, you make films purely on instinct?

Dev Anand: Relying on anything else is more dangerous.

RD: But, aren’t flops costly?

Dev Anand: I manage because, for one thing, I’m not extravagant. Then I’ve got the infrastructure—our own recording studio for post-production work. And I don’t pay myself. You should be courageous enough to lose money. Flops don’t break me because I have the confidence that things will work out in the long run.

RD: Looking back, you think someone up there has created your own life story?

Dev Anand: I often wonder. I came to Bombay with no connections, no letter of recommendation. I lived in a chawl, went hungry, but I wanted to become a film star. Even as I stood in a queue for a cinema ticket, I dream of the day my face would be on those posters. To succeed, you have to single-mindedly pursue a dream.

RD: Which was the low point of your struggling days?

Dev Anand: The day I was forced to sell my beloved stamp collection. I spent my last coins on a bus ride into town, then walked along the main road very, very hungry. In my bag were the stamps. I found a stamp seller who bought it all for INR 30. The deal was a godsend, but I was also heartbroken—that collection had many rare stamps. Looking back, however, I don’t regret the day. It made a man out of me

RD: Then, things got better.

Dev Anand: Not right away. A couple of studios rejected me outright, but I kept knocking on doors, never losing hope. I got an accounts job, which I quit within days. I then worked for a while at the military censors office where I pored over soldiers’ letters. A routine desk job, but one where I got into the minds of lonely men pining for their wives, their sweethearts, and learnt about people’s deepest desires. It was very educative.

RD: And you continued looking for work as an actor?

Dev Anand: Yes, off and on. I went to the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), where the senior actors never took me seriously. But I was watching, learning. In 1945, when I heard that Prabhat Studios was looking for a young lead actor, I met the boss was sent to Poona, screentested and hired. My salary was INR 400 a month, a lot of money in those days. But it wasn’t just the money—I was living my dream.

RD: Prabhat was where you met your friend Guru Dutt.

Dev Anand: I first bumped into Guru Dutt, then an assistant director at Prabhat, and just couldn’t keep my eyes off the shirt he wore. He introduced himself, and I said, “That’s a nice shirt you’re wearing.” “Same to you,” Guru retorted. We had a good laugh—we were wearing each other’s shirts, inadvertently swapped by the dhobi. That sealed our friendship. Guru was the best friend I ever had. We made an unwritten pact: If I ever produced a film, he’s direct it, and if he ever produced one I’d be the lead actor. I kept my promise with Baazi and so did Guru with his CID.

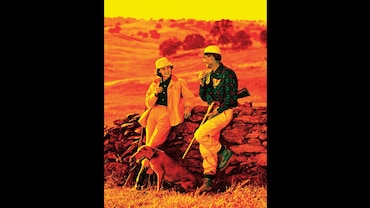

Dev Anand made two film versions of R. K. Narayan’s novel The Guide. He co-produced an English version with Nobel-winning author Pearl S. Buck. It flopped badly. Undeterred, he went ahead with the Hindi version, roping in his younger brother, Vijay ‘Goldie’ Anand as director. Unconventional even by today’s standards, Guide became a landmark in Indian cinema.

In the film, Dev Anand played Raju, a smooth-talking tourist guide living with another man’s wife, Rosie. Raju goes to jail for forgery. Freed, he wanders into a village where illiterate rustics make him, their guru, revering every word and act of his. Roger is pressured into undertaking a fast to get rain for the drought-stricken village. The film ends with Raju’s death, and the arrival of the monsoon.

Dev Anand and Waheeda Rahman in Guide

Dev Anand and Waheeda Rahman in Guide

RD: How did our audiences accept Guide’s adulterous heroine?

Dev Anand: Even information minister Satyanarayan Sinha had worries about a film portraying adultery. But I told him, “R. K. Narayan got a Sahitya Akademi award for the novel. So what’s wrong with the film based on it?” That settled it. Also Goldie and his collaborators had made Rosie a sympathetic character. But Guide was a tough film to make. It was enormously expensive, and people call me mad for persisting with the Hindi version, after the English one failed. Sure, I was mad—but creativity often requires that streak of madness.

The initial audience reaction to the Hindi Guide was one of confusion. We were all depressed. Then, slowly, the film grew on the viewers. Distributors, who’d complained about losing money, called again to tell us that the crowds were coming back. Guide snowballed into a big hit. In Bombay, the monsoon that year was much delayed, causing an acute water shortage. And, like in the film, the day Guide was released it poured over the city. Our posters read “Guide Brought the Rains!” Sometimes even the elements favour you.

RD: The novel got awards, but a movie with the same theme caused apprehensions. Does this ambivalence reflect a deeper problem?

Dev Anand: It’s got to do with the way we censor films. I once walked out of a Censor Board meeting because I thought they were stupid. They wanted to cut a scene from my film Main Solah Baras Ki, where I was shown drinking. They said “Why should you, with such a respected image, be shown drinking?” “I’m not playing an image,” I told them, “I’m playing a character, who wants to drink.” They said, sorry and cut the scene out. I retaliated with Censor.

RD: To prove what?

Dev Anand: To prove that censorship in this country is all wrong. I’m not advocating nudity or gratuitous sex and violence. My problem is with our obsolete and dogmatic code of moral censorship, that’s made worse by conservative bureaucrats who stick by it, even as the world is moving ahead. They want to censor films when cable TV and the internet are showing worse things. Urdu poets have written exquisite verses on liquor and the Kama Sutra is a part of ancient Indian culture. While the solution may not be to do away with censorship, we need to liberalize the code after a democratic debate.

RD: That brings to mind your 1977 protest against Indira Gandhi’s Emergency.

Dev Anand: They pushed us film people to the wall, and I got annoyed. They banned Kishore Kumar songs from All India Radio and Doordarshan because he didn’t toe their line. And they called us to New Delhi to sloganeer for Sanjay Gandhi. I met information minister V. C. Shukla and told him, “I’ll take part only if you admit we’re now a police state.” He backed off. Then opposition leaders approached me for support. I spoke at their rallies and even formed the National Party of India (NPI). But after the Emergency, we were disillusioned with the non-performance of the Janata coalition and wound up the NPI. In any case, I was in love with filmmaking. I’m not cut out for politics—you need to be cold-blooded for that.

RD: So what’s your prescription for better governance?

Dev Anand: We should get the country’s best people to represent us in Parliament. You can fight today’s system only with literacy. A literate and enlightened population will not allow goondas to rule them. But again, I see little hope, unless young liberal minds enter active politics.

RD: You were on the Delhi–Lahore bus with Prime Minister Vajpayee in February 1999. What was it like returning to the city where you attended college?

Dev Anand: It was a great feeling revisiting Government College Lahore after nearly 60 years, the same arches, the same hostel, classrooms and playgrounds. Only, the buildings now had Muslim names.

In Lahore, I was at a posh restaurant where a flautist in his 50s was performing. And guess what? He was playing the tune of ‘Jaayen Toh Jaayen Kahan’, from my 1954 film Taxi Driver. He told me he’d seen all my films and could play any song from them. I thought he was pulling a fast one and named ‘Shokhiyon Mein Ghola Jaaye’ from Prem Pujari. He played it so well that I kept thinking: The same language, same music, same culture, same cuisine, same temperament—then why two hostile countries?

Adding his own impish touch to Bollywood’s seduction routine, Dev Anand wooed scores of heroines on the screen, even falling famously in love with one of them. He proposed to actress–singer Suraiya, but she turned him down. Then, in 1954, during a lunch break on a film set, Dev Anand quietly married another co-star, Mona Singh, whose screen name was Kalpana Kartik. They have a son Suneil, and a daughter Davina.

RD: Did you consciously develop your trademark mannerisms as part of your star image?

Dev Anand: It’s the way I am. Also, since most of my film scripts were written around ‘Dev Anand’, I just had to be myself. Love scenes especially came very naturally to me. Chivalry, kindness and good manners—values that are never outdated—were ingrained in me

RD: At home?

Dev Anand: Yes, by my mother, perhaps. She was so kind, loving and gentle. She died of TB. There was no cure for it then. My siblings were either away at college or too young, so I was the one closest to her and spent a lot of my time nursing her. Every morning, I brought her goat’s milk, which was prescribed by the doctor. I think I’ve inherited a lot from her.

RD: Who’s your all-time favourite film star?

Dev Anand: Ingrid Bergman. God, what grace, what charm! And all this in a sweet, non-sexual kind of way. Any man would feel so good to be with her.

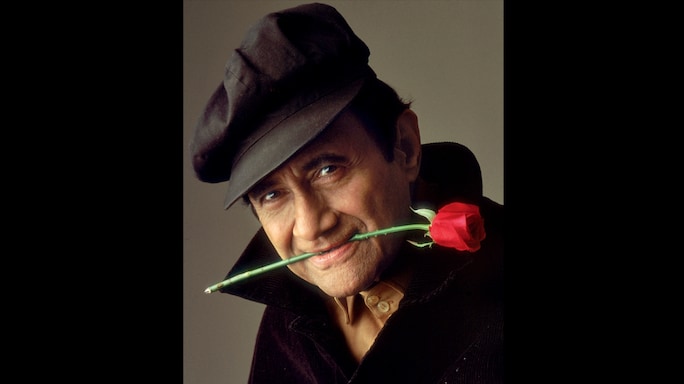

Dev Anand, in 2010

Dev Anand, in 2010

RD: Falling in love is a different feeling.

Dev Anand: One falls in and out of love. I once had a teenage crush on a girl in Lahore. Our history professor’s daughter. But nothing happened. It was only from a distance. When you’re seriously in love, you propose to a girl and say: “I can’t live without you.”

RD: That happened with Suraiya.

Dev Anand: Yes, she was my first, and only, real love. I wanted to marry her. I even bought a ring.

RD: She wanted the marriage?

Dev Anand: I think so. She was saying, “I love you, too.” But some members of her Muslim family dissuaded her. And remember, she was a big star then, and I was a nobody. I wept like a child on my older brother Chetan’s shoulder when she broke up with me.

RD: Film lore has it that you still send her a rose on her birthday.

Dev Anand: No, never. Once I was through with her, I got busy with my production company Navketan, and married Mona.

RD: On the rebound?

Dev Anand: You may call it rebound. You find yourself in a vacuum, you need emotional security, and you suddenly find this fantastic, educated girl. Mona was a Christian, but we had no problems getting married because her family was liberal.

RD: Then why such a quiet wedding?

Dev Anand: I’m not anti-social, but I don’t like this big tamasha of the groom riding in on a horse with a band-baja. To me, it’s ridiculous.

RD: Some of today’s film stars dance at these wedding tamashas for a fee.

Dev Anand: They’re selling their souls. I’d never do it.

RD: Finally, something a lot of people wonder about: What’s the secret of your youthful looks?

Dev Anand: I think it’s the mind. It dictates to the body. I’m mentally—and therefore physically—active. I can work 17 hours a day, and make do with just five or six hours of sleep. I don’t smoke, drink or eat meat. Also, my sorrows don’t stay with me because I’m very optimistic. For me, the next moment is always a great moment. I forgive easily. That makes you live long. If your hurt stays, it brings about your downfall. Who knows, I live another 100 years!