- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Classic Reads

- /

Wise Animals I Have Known: A Naturalist describes What the Wild can Teach us

A naturalist is bowled over by the instinctive acts of animals

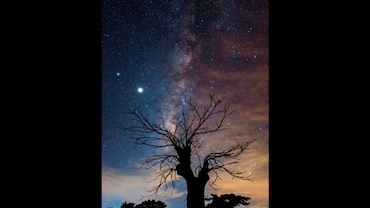

photo: getty images

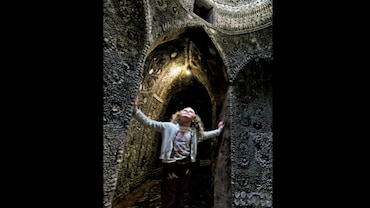

photo: getty images

Most of my life has been spent in getting to know animals. When I was five or six, the animal was an ol’ houn’-dawg–one of the wisest persons in the world I thought at the time. I may have been right. Later it was rabbits, guinea pigs, white mice. Then in my adult life as a naturalist it has been deer, raccoons, skunks, foxes and a long parade of other wild animals observed in close intimacy outdoors. If I live to be 80 and still greet the mornings with a praise like prayer, it will be because I knew animals.

They are very close, said Saint Francis, to the paternal heart of God. I think they must be. By instinct, an animal puts infinite trust in life. This morning at sunrise I watched Thomas, our cat, greet the new day. Thomas is now (in human terms) going on for 80.

Every morning I share daybreak with him. It is great medicine. First there is his rush up the cellar stairs, lithe and springy as a tiger, from the place where he sleeps by the furnace. While I fix his food I watch him. He always begins with the ritual of stretching. Nothing trivial or hasty, mind you, but a leisurely, carefully relished luxury that does him as much good as a holiday. Left front paw, right front paw, now both hind legs, now a long bend of the back ... aaah! A brisk shake; the big green eyes open wide; the ears perk up.

He dashes to the French window, rears up with forepaws on the glass, and peers out all quivering and tail twitching with excitement. Sunshine! Trees! Great heaven, there is a leaf blowing hop-skip across the lawn!

Thomas has looked out through this same pane hundreds of mornings, but every time it is fresh and challenging and wonderful. And so with breakfast, you’d think he had never seen this old chipped dish before. He pounces on his food like a man finding uranium. Then, when the last bit has been neatly licked from the plate, comes the ecstatic moment for going out to the new day.

Thomas never just goes through the doorway. (Animals don’t take these moments lightly.) First he glides halfway through, then stands drinking in the sounds, scents, sights out there. Another inch or two and he stands again. At last, very slowly, he slips over the threshold. If so much wonder were to hit Thomas all at once he could hardly stand it.

Now he rushes to the middle of the lawn and there this octogenarian performs a riotous caper. He takes a flying jump at nothing in particular, then zig-zags after non-existent mice. He leaps in the air and claps his paws on invisible butterflies. Then some quick flip-flops, rolling over and over, all four paws waving. In a minute it is finished and he steps gravely off to his day’s adventures.

What better lesson in living could one have? Here is joy in every moment, an awareness of the electric excitement of the Earth and all that’s in it. One further lesson from Thomas: when he sleeps, he sleeps. He curls up in a ball, puts one paw over the top of his head and turns himself over to God.

All animals give themselves wholeheartedly to the joy of being. At dusk, in my woods, flying squirrels play aerial roller-coaster. I have seen an old fox batting a stick in absorbed rapture for half an hour. Children react thus simply to the world about them, before reason steps in to complicate their lives.

One summer dusk I watched a buck deer browsing along a pasture hedgerow. His whole being was given over to the taste of the earth-cool grass, the caress of the slanting evening sun on his tawny flanks. He was as relaxed as putty. Nature was saying to him, “Taste, and enjoy yourself, old man,” and he was doing just that.

Suddenly a snake wriggled almost under his nose. In a flash the buck became a taut, fighting fury. “Get it!” said Nature, and he plunged to answer. Slash! Twack! The sharp, cutting hoofs flailed and in a moment it was over.

Then the voice said to him, “Back to your peace and your browsing, old man.” All knots of fight and fear were gone out of the buck’s body; again free and relaxed he sauntered up the pasture hill, and the soft dark of evening wrapped around him like an arm.

If animals can be said to have a philosophy, it is as simple as this: when Nature says, “I give you the glory of the senses and of awareness, and the splendour of Earth,” surrender yourself to these things, not worrying if it looks undignified to turn somersaults at 80. When the word is ‘fight’, pitch in and fight, not weighing hesitant thoughts about prudence.

“Rest,” says your monitor. “Play.” “Sleep.” “Feed and breed and doze in God’s green shade by the brookside,” each in its season. Heed the voice and act. It is a simple philosophy. It holds the strength of the world.

Animals do not know worry. What bird could raise a family if worried about the problems to be overcome, the impossible number of feeding trips in a day to keep those clamouring mouths stilled with food? That is not the way birds or animals respond to life. Nature says, “Feed them!” And the mother bird goes ahead and does it. Between dawn and sunset a tiny wren must make hundreds of such round trips to feed her brood.

An animal doesn’t know what brotherhood means, but when it hears the call “Help!” it answers instinctively. If a prairie dog is shot, the others in the prairie-dog village come tumbling out, not giving a hang for gunfire, and haul their fallen fellow underground. Big-game hunters have seen elephants, disregarding danger, lift a wounded comrade to his feet with their tusks and, supporting him by one member of the herd on each side, help him walk to the forest depths.

Even small birds work miracles of valiance. I once nearly had the daylights beaten out of me by a pair of phoebes, of all things. I had spied their nest on the underside of an old wooden bridge across a stream and was working my way from boulder to boulder in the rushing water to have a close look at the nestlings. Suddenly Mother Phoebe shot past me, only an inch from my nose.

I had hardly recovered from my dodge of surprise when she turned and flew straight at my eyes. I jumped sideways and one leg went into the water. At that moment Father Phoebe dive-bombed, and his wings knocked my glasses off. These parents were acting on the message “Get him!” They did. I came out from under that bridge as if bears were after me.

Not only do the wild things meet life in all its aspects wholeheartedly; they greet death the same way. “Sleep now, and rest,” says Nature at the end. When my old dog Dominie died he lay down in a favourite corner, gave a long sigh and was gone.

I remember an old woodchuck that died in my pasture. As I watched him he stretched out on a sun-warmed stone, breathed his last and surrendered himself to what Nature was saying to him. To do that could not have seemed strange to him—he had been doing it all his life. In animals shines the trust that casts out fear.

From the Reader's Digest July 1954