Gandhi and the World

Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, delivered this speech as the chief guest of the Jamnalal Bajaj Awards 2005, Mumbai. In this edited version, Sen discusses how Gandhian values continue to resonate in a world vexed by difference.

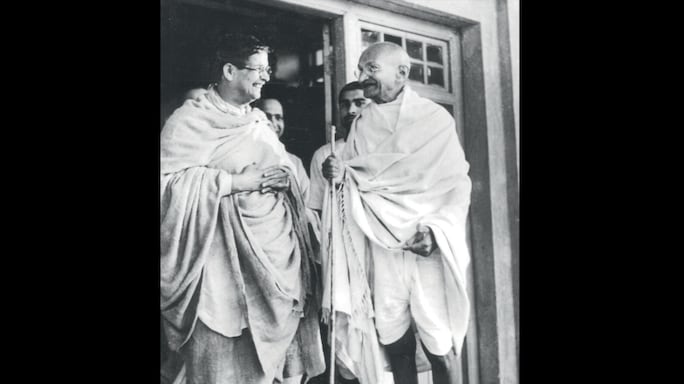

Gandhi with Kshitimohan Sen, scholar and grandfather of Amartya Sen, at Santiniketan,1940

Gandhi with Kshitimohan Sen, scholar and grandfather of Amartya Sen, at Santiniketan,1940

The aspect of Gandhian values that tend to receive most attention, not surprisingly, is the practice of non-violence. The violence that is endemic in the contemporary world makes the commitment to nonviolence particularly challenging and difficult, but it also makes that priority especially important and urgent. It is extremely important to appreciate that non-violence is promoted not only by rejecting and spurning violent courses of action, but also by trying to build societies in which violence would not be cultivated and nurtured. We would undervalue the wide reach of his political thinking, if we try to see non-violence simply as a code of behaviour. Consider the general problem of terrorism in the world today. In fighting terrorism, the Gandhian response cannot be seen as taking primarily the form of pleading with the would-be terrorists to desist from doing dastardly things, nor even just the form of dialogue and public interaction in peaceful ways with potential adversaries. Gandhiji’s ideas about preventing violence went far beyond that, and involved social institutions and public priorities, as well as individual beliefs and commitments.

For example, every atrocity committed in the cause of seeking useful information to defeat terrorism, whether in the Guantanamo detention centre or in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, helps to generate more terrorism. The issue is not only that torture is always wrong, nor only that torture can hardly produce reliable information since the victims of torture say whatever would get them out of the ongoing misery. But going beyond these obvious though important points, Gandhiji also told us that the loss of one’s own moral stature gives tremendous strength to one’s violent opponents.

The global embarrassment that the Anglo-American initiative has suffered from these systematic transgressions, and the way that bad behaviour of those claiming to fight for democracy and human rights has been used by terrorists to get more recruits and some general public sympathy, might have surprised the military strategists sitting in Washington or London, but they are entirely in line with what Mahatma Gandhi was trying to teach the world.

Gandhiji would have been appalled also by the fact that even though the United States itself, at least in principle, stands firmly against torture done on American soil or by American personnel, there are many holders of high American positions who approve of, and actively support, the procedure of what is called “extraordinary rendition”. In that terrible procedure suspected terrorists are dispatched to countries that systematically perform torture, in order that questioning can be conducted there without the constraints that apply in America. The point that emerges from Gandhiji’s arguments is not only that this is a thoroughly unethical practice, but also that this is no way of winning a war against terrorism and nastiness. Gandhiji not only presented to us a vision of morality, but also a political understanding of how one’s own behaviour can be, depending on its nature, a source of great strength, or of tremendous weakness. The value of that lesson has never been greater than it is today. I come back now to the question of cultivating social values, and social identities, that generate peace rather than violence. It is easy to see how much divisiveness has been bred by the federational view of citizenry in attempts to establish new democracies in countries such as Iraq or Afghanistan.

Gandhiji was critical of the official view that India was a collection of religious communities. When he came to London for the Indian Round Table Conference in 1931, Gandhiji resented the fact that he was being depicted primarily as a spokesman of Hindus, in particular “caste Hindus,” with the remaining 46 per cent of the population being represented by chosen delegates (chosen by the British Prime minister) of each of the other communities. Gandhiji insisted that while he himself was a Hindu, Congress and the political movement that he led were staunchly secular and were not community-based. While he saw that a distinction can be made on religious lines between one Indian and another, he pointed to the fact that other ways of dividing the population of India were no less relevant. Gandhiji made a powerful plea for the British rulers to see the plurality of the diverse identities of Indians.

Gender was another basis for an important distinction, which, Gandhiji pointed out, the British categories ignored, thereby giving no special place to considering the problems of Indian women. He told the British Prime Minister, “You have had, on behalf of the women, a complete repudiation of special representation,” and pointed to the fact that “they happen to be one half of the population of India.” Sarojini Naidu, who came with Gandhiji to the Round Table Conference, was the only woman delegate in the conference. Sarojini Naidu could, on the Raj’s “representational” line of reasoning, speak for half the Indian people, namely Indian women; Abdul Qaiyum, another delegate, pointed also to the fact that Sarojini Naidu, was also the one distinguished poet in the assembled gathering, a different kind of identity from being seen as a Hindu politician.

In a meeting arranged at the Royal Institute of International Affairs during that visit, Gandhiji also insisted that he was trying to resist what he called “the vivisection of a whole nation.” Much has been written on the fact that India, with more Muslim people than almost every Muslim-majority country in the world, has produced extremely few home-grown terrorists acting in the name of Islam, and almost none linked with the Al Qaeda. There are many casual influences here. But some credit must also go to the nature of Indian democratic politics, and to the wide acceptance in India of the idea, championed by Mahatma Gandhi, that there are many identities other than religious ethnicity that are also relevant for a person’s self-understanding and for the relations between citizens of diverse background within the country.

The disastrous consequences of defining people by their religious ethnicity, and giving priority to the community-based perspective over all their identities, which Gandhiji thought was receiving support from India’s British rulers, may well have come, alas, to haunt the country of the rulers themselves. In the Round-table conference in 1931, Gandhiji did not get his way, and even his dissenting opinions were only briefly recorded without mentioning where the dissent came from. In a gentle complaint addressed to the British Prime Minister, Gandhiji said at the meeting, “in most of these reports you will find that there is a dissenting opinion, and in most of the cases that dissent unfortunately happens to belong to me.” Those statements certainly did belong only to him, but the wisdom behind Gandhiji’s farsighted refusal to see a nation as a federation of religious and communities belongs, I must assert, to the entire world.