- HOME

- /

- Conversations

- /

- In My Opinion

- /

Fighting Disinformation

From Covid conspiracies to lies about the Ukraine war, traditional fact-checking is no match for the power of the crowd

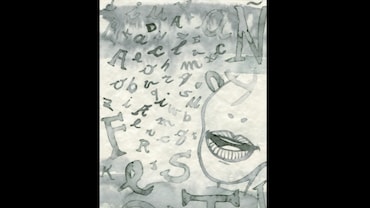

illustration: Elia Barbieri

illustration: Elia Barbieri

In recent years, the internet has become the venue for a general collapse in trust. Trolling, fake news and ‘doing your own research’ have become such a part of public discourse, it’s sometimes easy to imagine that the online revolution has only brought us new ways to be confused about the world.

Social media has played a major role in the spread of disinformation. Malicious state enterprises such as the notorious Russian ‘troll farms’ are part of this, but there’s a more powerful mechanism: The way social media brings together people, whether flat earthers or anti-vaxxers, who might not meet like-minded folks in the real world.

Today, if you’re convinced our planet isn’t round, you don’t have to stand on street corners with a sign, shouting at passers-by. Instead, you have access to an online community of tens of thousands of individuals producing content that not only tells you you’re right, but builds a web of pseudo-knowledge you can draw from if you feel your beliefs are being challenged.

The same kinds of ‘counterfactual communities’ arise around any topic that attracts enough general interest. I’ve witnessed this myself over the past decade while looking into war crimes in Syria, Covid-19 disinformation and now the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Why do counterfactual communities form? A key factor is distrust in mainstream authority. For some, this is partly a reaction to the UK and US governments’ fabrications in the build-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Sometimes, it stems from a sense of injustice around the Israel–Palestine conflict. These are of course legitimate positions, and are not by themselves indicative of a tendency to believe in conspiracies. But a pervasive sense of distrust can make you more vulnerable to slipping down the rabbit hole.

One way of looking at this is that government deception or hypocrisy has caused a form of moral injury. As with the proverb “once bitten, twice shy,” that injury can result in a knee-jerk rejection of anyone perceived as being on the side of the establishment.

This creates a problem for traditional approaches to combatting disinformation, such as the top-down fact-check, which might be provided by a mainstream media outlet or other organization. More often than not, this will be dismissed with: “They would say that, wouldn’t they?” Fact-checking outfits may do good work, but they are missing the power of the crowd. Because, as well as counterfactual communities, we’ve also seen what could be called truth-seeking communities emerge around specific issues.

These are the internet users who want to inform themselves while guarding against manipulation by others or being misled by their own preconceptions. Once established, they will not only share fact-checks in a way that lends them credibility, but often conduct the fact-checking themselves.

What’s important about these communities is that they react quickly to information being put out by various actors, including states. In 2017 the Russian ministry of defence published images on social media that it claimed showed evidence of US forces assisting Islamic State in the Middle East. Huge, if true—except it was instantly debunked when social media users realized within seconds that the Russian ministry of defence had used screenshots from a computer game.

I would go as far as to say that internet users who are heavily engaged with particular topics are our strongest defence against disinformation. At Bellingcat, a collective of researchers, investigators and citizen journalists I founded in 2014, we’ve seen this play out in real time during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Our investigation of the downing in July 2014 of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine helped create a community focussed on the conflict there that uses open-source techniques to examine, verify and debunk information.

In the weeks before the invasion, we gathered videos and photos of Russian troop movements that forewarned of the planned attack, and we debunked disinformation spread by separatists—including images of a supposed IED attack posed with bodies that, as we discovered, had been autopsied before they even arrived at the scene.

After the invasion started, many of the same people collected and geo-located images, including those of potential war crimes, that Bellingcat and its partners have been verifying and archiving for possible use in future accountability processes.

But how do you grow and nurture what are essentially decentralized, self-organized, ad hoc groups like this? Bellingcat’s approach has been to engage with them, creating links from their useful social media posts to our publications (all thoroughly factchecked by our team), and crediting them for their efforts. We also create guides and case studies so that anyone inspired to give it a go has the opportunity to learn how to do it.

But there’s more to do than simply waiting for crowds of investigators to emerge and hoping they’re interested in the same things we are. The answer lies in creating a society that’s not only resilient against disinformation, but has the tools to contribute to efforts toward transparency and accountability.

For example, the digital media literacy charity The Student View in the UK has been going into schools and showing 16- to 18-year-olds how to use investigation techniques to look into issues affecting them. In one case, students in the city of Bradford used freedom-of-information requests to uncover the unusually large number of high-speed police chases in their areas.

Teaching young people how to engage positively with issues they face and then expanding this work into online investigation is not only empowering, it gives them skills they can use throughout their lives. This is not about turning every 16- to 18-year-old into a journalist, police officer or human rights investigator, but rather giving them tools they can use to contribute, in however small a way, to the fight against disinformation. In their home towns, in conflicts such as Ukraine, and in the wider world, they really can make a difference.

Eliot Higgins is founder of the Netherlands-based Bellingcat investigative journalism network and author of We Are Bellingcat: An Intelligence Agency for the People. He lives in the UK. Copyright Guardian News & Media Ltd. 2022