TURNING OVER A NEW LEAF

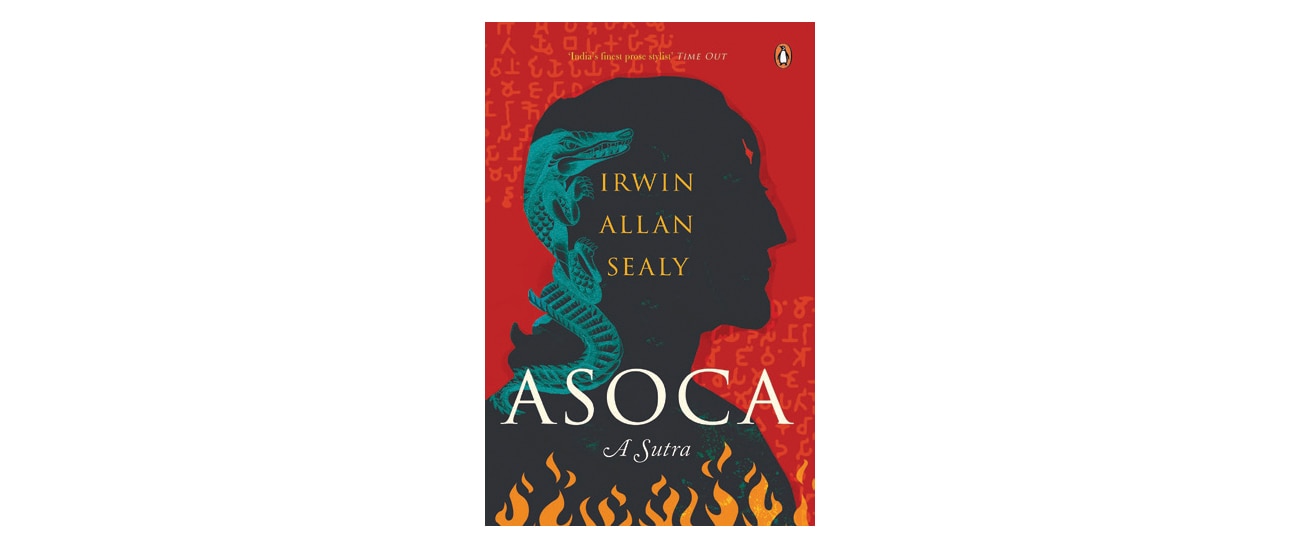

In Irwin Allan Sealy’s latest novel, we discover an Asoka who is more human than saint

Photo: Arun Pardesi

Photo: Arun Pardesi

Emperor Asoka ruled much of South Asia and played a crucial role in the spread of Buddhism in the 3rd century BC. But who was the man? What brought about his transformation from a warmonger to a practitioner and preacher of peace? Irwin Allan Sealy’s latest novel Asoca: A Sutra—an imagined memoir told in the voice of the ageing emperor, ‘Asoca’, after he has abdicated and retired to a cave—might provide some answers.

What drew you to write a book on Asoka?

A glimpse—quite late in life—of his famous Kalsi edict rock located in the very district where I’d spent a goodly portion of my life, Dehradun. The rock was pivotal in establishing an accurate chronology for our ancient history and in the deciphering of our archaic languages, so I was a little ashamed of having failed to visit this crucial landmark in my own backyard. I think the novel was part expiation.

In Zelaldinus (2017), the narrator was your alter-ego. Here, Asoka is looking back on his life as a 70-something man. Did your being close to him in age have any bearing on his reflections?

Certainly, it helped to be able to look back as Asoka himself might have to-wards the end of his life. I’d like to think that proximity—reflecting on life from a comparable vantage—gave the first-person narrative some authenticity. We don’t know for sure when Asoka was born or when he died, so his age is conjectural. Historians think he lived into his mid-seventies.

You said in an interview that the sorrow of Asoka resonated with your own experiences as a person. Can you elaborate?

I did have in mind a darkening of the screen—a sobering or sombering—that comes with advancing age. In fact, the Kalinga war came when Asoka was barely middle aged, but it appears to have profoundly changed—you could say aged— him. Sorrow is almost by definition an older person’s response; it goes much deeper than simple sadness, which is available to you at any age.

You make a distinction between ‘Asoca’ and ‘Asoka’. Could you tell us a little about the ‘k’ sound and why the difference? It was just a way of distinguishing my fictional character from the historical man. The ‘c’ was my proprietary mark, which allowed me to shape my man in any way I pleased. He was ‘my Asoca’ in the way Zelaldinus was my Akbar. (The Jesuits at court wrote his name, Jalaluddin, as Zelaldinus in Latin, and I thought Good, I’ll call my man that!) In Asoca the eccentric spelling is also a linguistic marker: There’s light weather made of the way people speak and how it indicates their social class or regional origins.

Were you already thinking of this book when you wrote these lines in Zelaldinus: “… Ashoka the great? Don’t make me laugh ...”?

Strangely, no. At that point I was Akbar. And of course, the poem was a one-off, a comic set-piece. The reader under-stands Akbar here is the edgy, imperial egotist looking for the nearest competitor. Asoka is more than the straw man Akbar sets up here. That’s part of the joke, which then goes still further with the ‘other guy’—Christ.

Of all your books, this one seems to be among the more ‘straightforward’.

Yes. In the past I’ve often chosen complex modes of story-telling. The form—say a nama or a chronicle, as indicated in the subtitle—was a clue to the strategy of the text. This time the strategy itself was straightforward. I set out to tell a plain unvarnished tale, something the sutra—or thread—exemplifies: no loops, no knots, just a continuous yarn. Hence Asoca: A Sutra.

How did you strike the balance be-tween taking creative liberties in the novel and staying faithful to the spirit of the man?

The edicts are what we know this man by, and their unique feature is their advocacy of non-violence and a message of tolerance that broke with the vaunts of all other rulers of antiquity. I needed to keep this quality front and centre without making a saint of the man. The man who emerges from the edicts is in fact very human: a bit humourless, a bit sanctimonious, a bit of a prig, so I tried to work those qualities into the book. There is also a tradition that Asoka was a cruel king who turned over a new leaf when he became a Buddhist. Now, I could have used this alleged transformation in a lurid way that made for melodrama, but in fact I was trying to create an ordinary man, neither saint nor sinner. Extraordinary men have their ordinary moments, and many of the liberties I take surround such moments in his life.

Tell us a little about how your visits to Kalinga influenced the book.

To stand by the Kalsi rock, or the one at Kalinga, is to step outside time. As you muse, you’re gathered up into a past that has vanished so completely that you’re obliged to reinvent it. Possibly that strenuous evocation turned me into a storyteller: recreating the times led to recreating the king. We all grow up with a smattering of Asoka, and I think I’d reached a tipping point where I was after more. I began by reading the edicts. The edict rocks should be places of national pilgrimage.

In the novel, Asoca doesn’t shy away from recounting war and bloodshed in great detail when he speaks about the signal he gave to “begin the killing”. Usually, one tends to bury one’s darkest mistakes, but not Asoca. What does that say about him?

It says he was an uncommon man, un-usually reflective, ahead of his time (as a ruler if not as a thinker—remember always that the Buddha preceded him in a sense that made him possible) and spiritually resourceful. Only an unusually strong personality could snatch victory from a moral defeat the way he did. To take a cynical view of his trans-formation is to miss a human triumph that is also a piece of admirable king-ship, because he proceeds to turn his awakening to practical and political ends—his programme of dhamma.

Asoka’s story is inspiring in that a man who spread destruction transformed after great penitence. Do you think our present-day leaders are capable of such introspection? For a revolutionary transformation of the kind Asoka underwent, the human material must be exceptional. I see no evidence of the necessary strength of character among today’s leaders, but there’s no such thing as a kali yuga any more than there’s ever been a golden age. History can throw up an aberration any time, just as it did in Gandhi’s day.

“Forgive yourself,” Asoca is told in the end. Do you think that is a good starting point on the path to redemption?

It is a prerequisite to wiping the slate clean, and that is a necessary first step on the path.

What are you working on now?

On a gazetteer of the Doon valley. Something along the lines of the Imperial Gazetteer of India, which was an extraordinary work of literature. Of course, that encyclopaedic work would simply be a point of departure: old forms are a springboard to new kinds of writing. My Gazetteer will be considerably more playful and will happily accommodate fact and fiction, something that would horrify any civil servant worth his salt, especially those staid Raj sahibs.