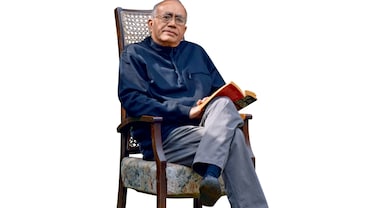

The Rebel's Manifesto

Actor Naseeruddin Shah says he has been resisting authority since he was a little boy. As he talks more about his craft, likes and dislikes, we see why going against the grain comes so naturally to him

PHOTOgraph by Danesh Jassawala

PHOTOgraph by Danesh Jassawala

Having been in the industry for 50 years, do you ever feel trepidation about how a new show or film will be received?

I should correct you. I have been in this industry for some 48 years. It'll only be 50 years in 2025. I did my first film, Shyam Benegal’s Nishant in 1975. I was still studying at FTII [Filmand Television Institute of India]when Girish Karnad, who was then director of the institute, recommended me for this film. I was lucky enough to get this part. Many actors were vying for it but they were all too good looking. (Laughs) What I thought would be my weakness helped me get my breakthrough.

I was really delighted because I suspected I wouldn’t be in demand for the heroic kind of parts that Hindi movies demand. And the thought of playing a sidey part would offend me because I saw so many great actors—Shriram Lagoo, Nilu Phule, Utpal Dutt—all reduced to playing caricaturish roles. I never wanted to play those kinds of parts. I was lucky to get a leading part right away with my first movie.

I felt trepidation while doing Nishant because I realized that if I messed this up, that would be the end of the story for me. I had a reputation of being sort of troublesome. Shyam had cast me against a lot of advice.But I had really resolved I wouldn’t let this go. I was very, very cautious, and was on my best behaviour. I would be reading my scenes well into the night.I realized then that nervousness was something that strikes actors who are not prepared. But to answer your question—I’ve felt trepidation when I have had to do song-and-dance numbers in films, but otherwise, no,not so much.

Where did this troublesome reputation come from? Would you not take to authority very well?

Ram Guha, who encouraged me greatly in the writing of my memoirs, feels I have an inborn resistance to authority. (Laughs) But yes, looking back, it does seem that I have like rebelling against authoritarianism. Whether it was my dad, or the teachers in school, who were pretty severe on us. These were the Irish Christian Brothers. Walloping a kid was fairly normal—slapping, kicking, punching, pulling the ear, all that happened.

And we took it. We felt teachers were allowed to do this. I often felt the urge to hit back, but I knew what it would result in. Maybe that urge is where it comes from. Maybe that’s why people still think of me as this rebellious character.

You were speaking about preparedness earlier. Given the regularity with which your face the camera, does Naseeruddin Shah disappear more easily into his character now?

I have learnt over the years that it is not an actor’s job to disappear behind a role. In much the same way as you can identify a painting or a dance performance or a piece of poetry, I don’t think there’s any harm if the performance by an actor is identifiable. It should just not be repetitive, and if it is, that repetition should not get in the way of the text. It’s, perhaps, too much to expect an actor to be so physically different from part to part that you don't ever think it’s this actor playing the role. I can only assume that one of the reasons why Daniel Day Lewis has now hung up his boots is because of this. How long can he keep drastically altering his personality, and emotionally investing so heavily in every part? I have often received this compliment—“We only saw the character and we didn’t see you”. I honestly think that has more to do with the writing. The writing in these instances is so impactful that it’s getting through despite the kind of acting you may have seen the actor do before.

Your next series, Kaun Banega Shikharwati, is a comedy. Would you agree with the claim that not enough people are writing good comedies anymore?

They never were. I don’t know why people can’t see the humour in their own lives, and why they always draw upon caricatures of the West. We just haven't found an indigenous sense of humour. It seems we are either only mocking one person’s disability or mocking the physical appearance of another. The Parsi, for example, is always an object of ridicule. The Sardar, till recently, was also precisely that.The Muslim was always the sacrificing good friend who would give up his life in the end. The Christians were always drunkards. This was all cast in stone.So, we fall back on the traditions of the past. Now, who do writers who want to make funny films today have to fall back on? They only have the likes of Johnny Walker and Keshto Mukherjee.Luckily, we actors had a Balraj Sahni and a Dilip Kumar. In Bengal, there was Pahari Sanyal. In Tamil and Malayalam industries, there were other actors, too, who were considered great. If they hadn’t been there, we—Farooq Shaikh, Shabana Azmi, Om Puri and I— would never have had the courage to attempt what we did.The next generation—Irrfan and his peers—has certainly gone beyond us.They are much savvier than we were.They are more cinema-literate. They understand the medium better, and they are much more skilful than we were at their age. So, each generation feeds from the last one. Comic writers,sadly, have nothing to feed on.

Shah, playing the Subedar in Mirch Masala (1987).

Shah, playing the Subedar in Mirch Masala (1987).

Kaun Banega Shikharwati releases on Zee5. Bandish Bandits streamed on Amazon Prime. Much is now made about how the advent of OTT has revolutionized entertainment.Your thoughts?

OTT is certainly now in the process of revolutionizing the way in which we watch movies and also of revolutionizing the way in which they are being made. Take my example. I’ve done five or six shorts—all quite wonderful movies. They were made by kids who were only about 25 or 26 and had absolutely fantastic ideas. They didn’t have to face the pressure of a producer sitting on their heads or the pressure of a Friday release, box-office collection, etc. So, a lot of them, I think, have been encouraged. They maybe now feel empowered to attempt something beyond the conventional. Plus, the OTT shows are encouraging young filmmakers to explore unconventional and thought-provoking content. Also, so many marvellous actors have appeared. So many technicians, so many editors are getting employment, all of whom are so deserving as they have always done such a good job.

You recently said you have done everything you wanted to do as an actor. What motivates you to go to work now?

The fact that I still love movies deeply.They were my first flights into fantasy.I think I saw my first movie when I was four years old. It always transported me somehow. I can’t quite believe I've spent almost 50 years of my life in this business. There are times when I wonder if all this has been a dream because I’ve lived my life exactly the way I had wanted to. Sure, I’ve had my ups and downs, but I don’t think I would have been this happy if I were in any other profession. So, here what keeps me motivated—if it’s apart exactly like the one I have done before, or if it’s content like what I have done before, I don’t take it. Also,If the content doesn’t say anything beyond the obvious, I don’t do it. I still turn down quite a bit of work, and yet I’m overloaded. I thank my stars for that because I’ve been extremely busy, even after lockdown. OTT really has given actors of my age group tremendous exposure.

Naseeruddin Shah in a still from Shyam Benegal’s Mandi (1983).

Naseeruddin Shah in a still from Shyam Benegal’s Mandi (1983).

When you think back to films like Nishant, Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro and Mandi, do you ever feel nostalgic?Do you ever regret that no one seems to be making films like that anymore?

A lot of the time they make better films today. Those 70s films were good, they served their purpose, but they're often overrated. What they did is that they gave the next generation something to build on. Filmmakers today are equipped with better craft than makers of the 70s and 80s.For instance, they have more of an empathetic attitude toward actors.

Whereas, early in my career, I could sense this hostility between directors and actors. As a result of all this, I find much better performances are now coming forth. Actors like Vijay Raaz and Gulshan Devaiah are surprising you with every performance they give.And for that, the directors must surely also get some credit.

Is there a sense of community that unites the film industry? Has that camaraderie been eroded?

People are all fence-sitters in the industry. We are the greatest hypocrites in the world. We sing of Hindu–Muslim fraternity, but I don’t think we believe in it. The fact is that there is perhaps resentment at the realization of how much the Muslims have contributed to the film industry, since the time it began. The Parsis and the Marathis were the pioneers, but the Punjabis and Muslims came in very quickly. One can’t think of a single department of the film industry in which the Muslims were not heavily involved—production, direction, music, writing, carpentry, light boys, you name it. Everywhere you go, you hear Muslim names being yelled out. There was Mohd Rafi, Mehboob Khan, etc.,etc., and now, of course, there are the three Khans. But from what I can see,some kind of attempt to replace them is on. I will clarify that I don’t know much about this industry, that I don’t have any friends who belong to it, and I never mingle with these people.But, yes, it does look suspiciously like the powers-that-be want to work to control this industry and utilize it in some way.

Naseeruddin Shah and Ratna Pathak Shah in Motley’s production of Dear Liar

Naseeruddin Shah and Ratna Pathak Shah in Motley’s production of Dear Liar

In 2007, you acted in the Pakistani film Khuda Kay Liye. You are soon going to be seen in a Bangladeshi sci-fi film called Project Ommi.How exciting are these South Asian projects?

I haven’t shot in Bangladesh before,but I am looking forward to it. Lahore, I did shoot in, but that was about 20 years ago. I visited Lahore several times after that, and I always had great fun over there. We also performed our plays there several times at the Faiz Foundation. To say that they are the most hospitable people in the world is a cliché. Everybody knows that. Incidentally, I did another Pakistani film in Punjabi in 2013, which wasn’t that much seen. It was called Zinda Bhaag.The thing is that they have made so many bad films for so many years that they're really struggling. They are trying to forge a new idiom, but the thing is that they are at it. They’ll come up with something, I’m pretty sure.

You’d speak with Irrfan often during his last days, but what was acting with him like?

His technique was invisible. He didn't waste time sitting by himself or clutching his forehead. There was none of that getting-into-the-zone kind of nonsense. He would act normal when he was with us and then when the moment came to walk into the acting space, there was a transformation. It was quite something. I really envied the seeming lack of effort.I think it had something to do with his normal confidence. He had this right from the start. He always had this ease.He never acted like it was a matter of life and death, but that said, I do think that he took it all extremely seriously.

Om Puri and Naseeruddin Shah in Vishal Bhardwaj’s Maqbool (2004)

Om Puri and Naseeruddin Shah in Vishal Bhardwaj’s Maqbool (2004)

What was it like to contract pneumonia at a time the world was still gasping from COVID?

It was scary because I feared it might be COVID in disguise. But the doctors,I knew, would not have kept me in the hospital if it was. It was odd. I remember deciding to get my life in order.Let’s just say it was timely reminder.

How has the pandemic affected your theatre group, Motley?

You never do think anything is final till it actually goes on the floor, and I had a couple of things stewing which I wanted to get working on. But it’s been two years and none of them has happened. I hope to get them moving now. More than Motley, the pandemic hit theatre owners really hard. In Mumbai, theatres have only been allowed to open to 50 per cent capacity and Prithvi is the only one that has opened. It’s affecting everyone—theatre groups, theatre owners, the light-hire people, the set-hire people. It looks grim.

(Left to Right) Ravi Baswani and Naseeruddin Shah in Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro (1983)

(Left to Right) Ravi Baswani and Naseeruddin Shah in Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro (1983)

You remain engaged in public discourse despite the threat of controversy. What drives you to keep speaking up and speaking out?

The concern, I suppose. Even though that concern gets interpreted as fear. I definitely don’t want to sound like a persecuted Muslimsaying I am scared in this country. Also, I’ve never said that, but, yes, that line gets attributed to me time and again. I have never said I’m scared. I did say I feel concerned about my children, but that’s all. So, what drives me to keep speaking is that I think if you don’t speak up, you are a collaborator. If there is something you feel strongly about and you don’t speak up, then you’re approving of what's going on. It’s important to say what you believe.