All You Can Eat

Nobel laureate Abhijit Banerjee’s book of recipes will change your kitchen, and, possibly, your life

PHOTOGRAPH BY BANDEEP SINGH

PHOTOGRAPH BY BANDEEP SINGH

On the day Abhijit Banerjee spoke to us via Zoom last month, he was thinking of making himself an endive salad with walnuts, some apple and a little blue cheese. “The range of flavours is stunning,” he claimed. “The apples are there for sharpness, the walnuts for nuttiness and then I add a little mustard for some bitter-sweetness. It's just wonderful!”

There is something very tangible about the Nobel laureate’s delight. It makes it hard to not salivate. Cheyenne Olivier only makes the envy worse when she reminds Banerjee that this French salad used to be a “staple” when she worked with him in Boston.

Olivier, an illustrator, has joined our call from France. For three years, she pitched in as an au pair, helping Banerjee and his wife Esther Duflo look after their two children. She remembers this time with much affection. “Abhijit could never be a boss,” she smiles. “I started gradually in the kitchen. I’d chop some onions, maybe some cilantro, but I then started doing full dishes under Abhijit’s supervision. I was soon proposing my own things. For three years, we cooked at least two meals, almost every day.”

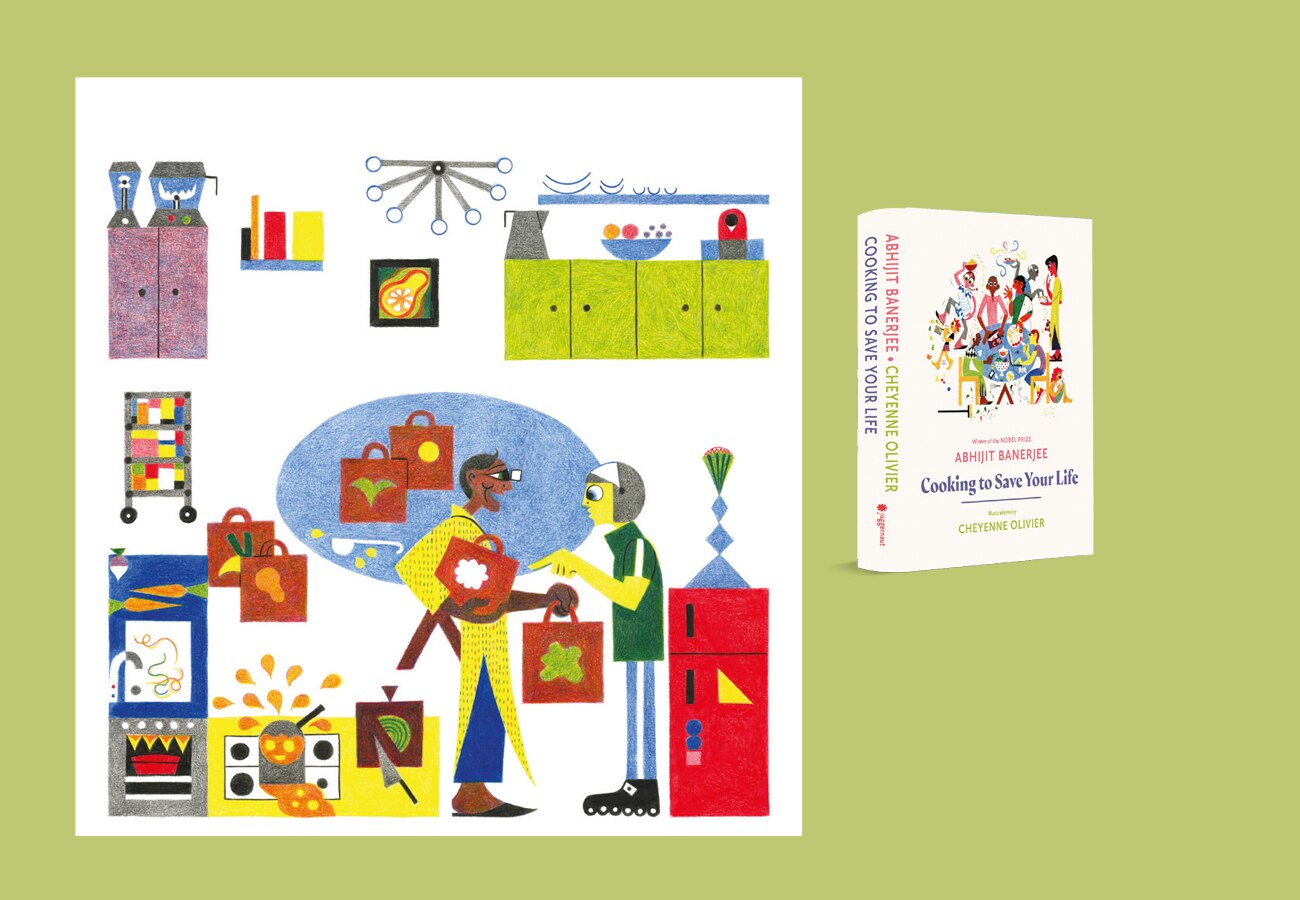

Written by Banerjee and illustrated by Olivier, Cooking to Save Your Life is quite obviously a kind of collaboration that often only results from a deep, lasting familiarity. An altogether unusual cookbook, Cooking to Save Your Life won't actually save your life—it seems a lot more interested in taste and relish than calorie intake—but it could, sadly, make impossible for its readers the excuse, ‘I cannot cook to save my life’.While Banerjee’s prose and recipes are both equally lucid, Olivier’s geometric drawings make you hungry without ever being intrusive. There’s comfort here, but, also, sustenance.

Illustrator Cheyenne Olivier believes food recipes should be adapted to our daily lives

Illustrator Cheyenne Olivier believes food recipes should be adapted to our daily lives

Not only is Banerjee averse to the hyperreal aesthetics’ of most cook-books—recipes, he writes, are only ideas, starting points—he sometimes even gets frustrated with the cook-books he does like: “They keep wanting to refine things. There’s this idea that one more step will make it better. The attitude in our cookbook is very much the opposite—let’s not try to go for perfect. We have an hour-and-a-half to get food on the table with six guests about to arrive. Our recipes, as a result, are not as elaborate.”

When Banerjee’s guests do finally arrive, some are readily deployed,while others add to the smells of his kitchen the sound of their chatter. Eating together can foster community, but the social scientist’s book suggests that cooking can, too. For Olivier, the myth of the solitary cook, “alone in his ideal kitchen, facing his ingredients all by himself”, is one she and Banerjee tried to break. “Most cookbooks assume you’re going to be in this white cube and everything will go perfectly. That does not happen.”

Olivier’s illustrations do, of course, define the book’s pleasing aesthetic, but they also serve a more crucial purpose. Since they are only approximations of Banerjee’s recipes, they help remove a nagging pressure that several home and amateur cooks feel—that of always getting it right. “People often get lost when they try to exactly follow a recipe. That leaves no room for playfulness or creativity,” says Olivier. “Also, sometimes you don’t have an ingredient or a gadget. That’s when you adapt the recipe to your own, very practical life.” Banerjee adds that maybe only five of the recipes in the book are strictly original: “Nothing is original. I think in most forms of art, you start by playing with a template.”

Whether it’s sesame-crusted potatoes or rosemary-soya lamb chops, Cooking to Save Your Life consistently endeavours to ease the cook’s stress, making her time in the kitchen fun and, also, fruitful. Abhijit Banerjee—the MIT economics professor—and Abhijit Banerjee—the gourmet cook—we see, both have an interest in alleviation. Banerjee’s introductions to each of his dishes and sections further make apparent an oft-forgotten truth—our identities, no matter how disparate,are almost always porous. Through the book, ‘the themes of poverty and inequality, want and need, conservation and climate change, power and gender, self-expression and conformity keep coming back’. Banerjee’s recipes are together a manual—we learn what to eat—but in their understanding of how we came to eat what we do, as in their soft prodding—why we must, perhaps,eat differently—they are also a guide.

A COLOURFUL PALATE

Even as a child, Banerjee says, “the kitchen is where things happened.” He remembers popping peas when he was six, taking apart cauliflowers, mixing cake batter, licking it up when no one was looking. “My mother was really very busy. She worked, ran a household, and added to that, my parents had a very active social life. This combination meant that if I had to catch her,it was in the kitchen. Our time there was our way of being together.”

Olivier, on the other hand, grew up without her mother. She says, “It was my father who did all the ground zero cooking. As a result, I grew up thinking cooking was a shared activity. It was only later that I realised this was not true for most households in France.” In Cooking to Save Your Life, Banerjee recounts a family picnic he went to as a young boy. While the women prepared the khichuri, chutneys, fritters and vegetables, a boisterous uncle took charge of the meat. Predictably,perhaps, it arrived dry and, also, late.“Cooking maybe less of a gendered activity today than when I was growing up, but we are still a long way away from gender equity. I feel the day-to-day boring cooking is still heavily feminized, unlike the flourish, which a lot of men take pride in. That’s a good starting point, yes, but who produces the ‘meal zero’ every day—that’s usually women.

”Introducing his vegetable recipes, Banerjee writes, ‘Taming vegetables tends to be classic women’s work—painstaking and life-sustaining, but somehow invisible.’ Vegetables clearly matter to Banerjee. From stir-fried cabbage to begun poshto (aubergine with poppy-seed paste), he covers the gamut in his cookbook.When Banerjee moved to the West,he first felt dismayed—“The quality of vegetable dishes was really not good.”He missed the “stunning” quality of vegetables in Kolkata: “We were not very rich. Often times there was just 60grams of fish to go around, so we had all these other vegetables—dal, ghonto,chhechki, dalna—to fill up with. You got to your tiny piece of fish only after you'd eaten all that great cooking.”

Having started with “a completely different vocabulary of eating”, Banerjee often came away from his travels with the same complaint: “My god, the food was bad!” Strangely, Cooking to Save Your Life never reflects this early distaste. Banerjee’s recipes for Spanish garlic soup, Moroccan zaalouk, and South Indian style stir-fried brussels sprouts all seem evidence of a cosmopolitanism that is expansive and inclusive. Travel and migration, one feels,inevitably widens horizons, and with it, our palate, too.

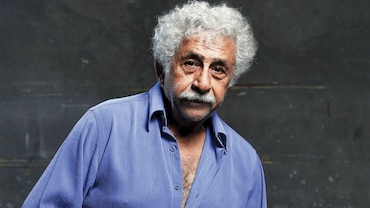

Abhijit Banerjee prefers cooking his own meals to ordering in or going out

Abhijit Banerjee prefers cooking his own meals to ordering in or going out

“But it can also contract it at the same time,” counters Olivier. “You open up, but you also hang on to food that is for you the best representation of home.” In the years that she was in the US, Olivier says she would invariably find herself making a French salad for lunch. “That’s my comfort food,and we’d cook Indian food three days a week because that’s Abhijit’s.” Days before Massachusetts went into lockdown last year, Olivier says she and Banerjee stockpiled Indian ingredients in an effort to “have everything covered”. Banerjee, for one, never takes the right ingredients for granted. He knows how challenging it can be to get them.“But I do also feel that [migration] can make you more conservative. You default to something that’s comforting,not necessarily creative. You’re eating a lot of nostalgia.”

NEITHER FISH NOR FOUL

‘I consider dal to be India’s greatest contribution yet to human civilization,’ Banerjee writes. ‘Ahead of chess and zero.’ If it came to it, Olivier, we think, would back her collaborator’s dramatic assertion. Author and illustrator both share an unmistakable, great love for reputedly humble dal. Growing up vegetarian, surrounded by friends who ate cold cuts with every meal, Olivier found recourse in lentils. While Banerjee daydreamed his way through prosody and physics lessons, thinking of jhaal muri (spicy puffed rice), Olivier spent her days in school yearning for split-pea soup with garlicky croutons.“This is why we get along so much,”says Banerjee. “You will find that same grammar of peas and garlic in a rich Bihar dal.

”In an age where vegetarianism has,perhaps, more to do with environmental and social consciousness than moral conscientiousness, the question almost asks itself: Did Olivier’s eating choices represent her taste or her politics? “For me, ideology came later. I remember seeing some of my friends, who had once converted to vegetarianism, become altogether obsessed with meats suddenly. I now think this happened because they were restricting themselves too much.It’s wonderful to want to be more environmentally sustainable, but being too ideological, I’ve seen, is not always the best way forward.”

Olivier’s geometric illustrations in Cooking to Save Your Life (left) are playful and evocative but never intrusive.

Olivier’s geometric illustrations in Cooking to Save Your Life (left) are playful and evocative but never intrusive.

Though Banerjee often ends up saying a vehement ‘no’ when someone asks him if he is vegetarian, his cook-book, oddly, has far more vegetarian recipes than meaty ones. “I guess part of the attempt in the book is to depoliticize the vegetarian-vegan conversation we have in the US, which is really,in a sense, more confrontational than it needs to be,” he says. Banerjee does, of course, concede that “everything is political”, but he is reluctant in endorsing the view that being vegetarian means one is morally superior. “That may be true, but it’s not helpful.” Borrowing his emphasis from the moral philosopher Peter Singer, Banerjee supports a more inclusive sense of eating—one that is mindful of environmental damage,animals, use of hormones—“but let’s not use it to beat people up too much”.

Vegetarianism, Banerjee stresses, is not a size that fits all. “You are, say, in rural south Bengal and you are poor. The easiest source of protein is often just the little fish you catch in the ricefield. You flavour the fish with some greens you have picked, putting together something from what’s available. We’re not talking about eight ounces of meat; just a small piece which makes all the other ingredients, the gravy, taste better.” Banerjee believes this in many ways is a “very good model for sustainable eating”.

Banerjee’s tone is never that of a proselytizer. When he writes that we should ‘adopt the tricks used by cooks in billions of poor families to make a little bit of meat go further’,he seems to be picking persuasion over-prescription. Meat, he suggests, doesn’t need to be the climax of our meals. “If you’ve already invested all your resources there, you might not have time or ingredients left for cooking the vegetables. But if you choose to rebalance how you cook, you’ll discover how good vegetables taste.”Banerjee’s planetary concerns can also, at times, seem very personal. Bluefish, for instance, often reminds him of the ilish maach (hilsa fish) he would once eat back home, but as a result of “climate change and overfishing for hundreds of years”, Banerjee fears that the fish will now migrate north“and soon we won’t get fresh bluefish in Boston”. Olivier, though, does find a silver lining: “Maybe we will again valorize the ingredients we have looked down on, again rediscover foods which we felt had no value.”

A SPOONFUL OF SUGAR

In the Kolkata neighbourhood of Banerjee's childhood, cash-strapped mothers had a somewhat quiet way of showing affection. They ‘would skip the milk and sugar in their own tea to be able to make a few extra spoons of kheer, so that they could say to us“Mishti-mukh kore jabi na?” (Won’t you please sweeten your mouth before you go?)Later, when the economist spent time in some of India’s poorest households, he was extended a similar warmth. The tea he’d be served was usually soaked in sugar.

‘Adding extra sugar is one way for a household to honour their guest.’ Never discounting the kindness of these gestures,Banerjee also sees in their excess a defiance. ‘The unexpected ice cream for your children, the cake that you should not have bought, the double dose of sugar in your guest’s tea—[all]just to prove, mostly to yourself, that you can, that you’re still able to be generous and free’.

Banerjee often reminds us of the poor in Cooking to Save Your Life, but at no point does he mark them as an ‘other’ who could be either pitied or dismissed. He finds in them the same capacity for feeling that the erudite prize: ‘As anybody who has ever spent time with actual poor people knows,eating something special is a source of great excitement for them (as it is forme).’ In Banerjee’s view, it isn’t hunger that unites us, “it is pleasure”. He says,“The theorising of poverty has been deficient precisely because it handmade enough space for pleasure. We think of the poor as machines that process calories to be productive. So,we then miss that people often don’t behave in ways we know.”

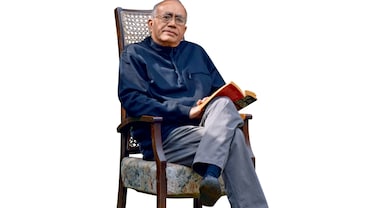

In 2019, Banerjee was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

In 2019, Banerjee was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

In the end, says Banerjee, it is also pleasure that proves to be the unifying theme of his and Olivier’s book: “Pleasure in the eye, in the tongue, pleasure in friends, pleasure in company. Interestingly, I have also found that all these forms of pleasure are not unrelated.They build on each other. Some of us can afford more expensive ways of doing things, yes, but it’s pleasure that remains a true universal.