GOSPEL TRUTHS

With his new novel, the increasingly prolific Jeet Thayil brings to the fore women who were once relegated to the peripheries of the Bible

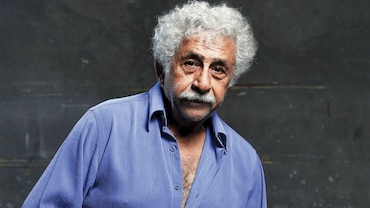

PHOTO: BASSO CANNARSA

PHOTO: BASSO CANNARSA

Poet, writer and musician, Jeet Thayil worked as a journalist for more than two decades and turned to writing fiction in 2006, shooting to fame with Narcopolis, his Booker-prize-nominated debut novel. His latest book, Names of the Women, centres around women characters from the Bible who have been misunderstood or forgotten, and retells familiar stories from fresh perspectives.

How did Names of the Women first take shape?

I’ve been reading the Bible since I was in my teens, as a literary text primarily, and I’ve quoted selections in early poems as a call-and-response device, using the quotes as a grounding element. On a recent reading, it struck me that some of the pivotal stories involve women who are never named or given narrative prominence. I wondered what would happen if a writer were to place the women of the Bible at the centre rather than the periphery of the story. Once that thought occurred to me, everything else fell into place and I wrote the novel very quickly.

How did you decide which women you would feature?

With some of the characters there was no question that they would feature. I wanted a living story paced like a thriller and some of the characters are so much larger than life they push their way into the narrative. We all know how the story ends, but that doesn’t take away any of the drama in its telling. As a novelist who wished to encompass barbarism, I couldn’t ignore Herodias and Salome, for example. And I couldn’t leave out the Virgin, or Mary Magdalene, or Mary and Martha of Bethany, sisters to Lazarus—they are central in so many ways to the story of Christ. But the peripheral characters interested me just as much. The poor widow who gives him her mite, Christ’s sisters who are never named, the handmaidens to Caiaphas who witness his trial and the women who stayed with him on Golgotha when the men, his so-called disciples, abandoned him.

Is there a challenge in writing about Jesus, or these episodes from the Bible in a way that is new or unexpected? “Does the figure of Jesus simply resist fiction”, as the New York Times puts it?

Nothing resists fiction, and that really is the point of the novelist’s enterprise. Everything is true and everything is permitted. All the writer has to do is find the point of entry. The figure of Jesus is and always has been a magnet for artists, who see something of themselves in his agony, his solitude, his martyrdom and the fact that he has come to represent the poor, the outsider and underdog. However organized religion may become, this is the inspirational truth about the figure of Christ. He speaks for the downtrodden.

How do you balance your interest in a feminist reading or rewriting whilst also keeping in mind the reality of the period, or the available material?

If I thought I was engaged in a feminist reading of the New Testament, I think I might have been paralyzed. That’s much too big a responsibility for a writer to assume. I thought of this novel as a way of returning certain marginalized figures to their central place in the Biblical narrative. And in a way, this is what I’ve done with every novel I’ve written.

We have seen retellings by writers from other places (Toibin, Crace etc). How is your approach in this subgenre of New-Testament fiction different as an Indian writer?

I don’t think it’s my place to say anything about this. I came to this novel as a writer, not as an Indian writer.It is a story that transcends time and place, not to mention culture and its ongoing crises. The great themes of the New Testament are enduring human themes: the limits of comprehension, the endless indifference of the universe, the violence endemic to us as nationalists, the need for love, empathy and compassion, the consolations of faith, the fact that jealousy, greed, generosity and heroism have always been with us.

Have your own religious beliefs shaped you in any way as a novelist?

I went to church as a child, and I remember in particular the services in the churches of Kerala when we visited on summer holidays. I attended Jesuit schools in Bombay, Hong Kong and New York, and I went to Sunday School, though my parents never insisted on any kind of overt Church-centric observance. I remember my father quoting Voltaire once, to the effect that people should leave the Church and return to God. I feel I am observant and God-minded, though not in obvious ways. I don’t know if any of this shapes the writer you become. I know that reading the Bible as a teenager gave me an early understanding of poetry, that it was language heightened and compressed in the service of direct speech.

Considering the Bible is a religious text, were you concerned at all about the possibility of giving offence? We are inside a moment in which an entire ecosystem has sprung up with the sole intention of taking offence. The people who thrive in this system look for new sources of outrage at all times: a pitiful way to live, really. Outrage fades; art does not. And it is the job of the artist to make art, whatever outrage it might generate.

In recent years novels seem to have taken precedence over poetry for you. How did that happen and which do you find more satisfying?

When I wrote poetry exclusively, I wasn’t a full-time writer. I had other jobs and wrote when I found time between deadlines. I’d always wanted to write a novel but I knew it required sustained labour on a daily basis, and I wasn’t able to do that. You need solitude, even isolation, and you need to think about one thing over a long time. None of that was possible when I was working for a salary. As for satisfaction, I don’t think I find one kind of writing more satisfying than the other. I’m happy just to write every day.

Your gap between writing novels seems to have become shorter. Is that due to a conscious effort?

It’s possible I’ve become more efficient. I think it helps to narrow your focus and tell one story, although it’s true, as I’ve said elsewhere, that ‘digression is the story entire’. I am an enthusiastic believer in the digressive interlude, but in Names of the Women there are none, and I think it is the better for it.