- HOME

- /

- Health & Wellness

- /

- Wellness

- /

How Dance can be Good for your Mind, Body, and Soul

Growing evidence shows that dancing can boost brain health and help manage symptoms of neurocognitive and movement disorders, including Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis (MS), Alzheimer’s, dementia and brain injury.

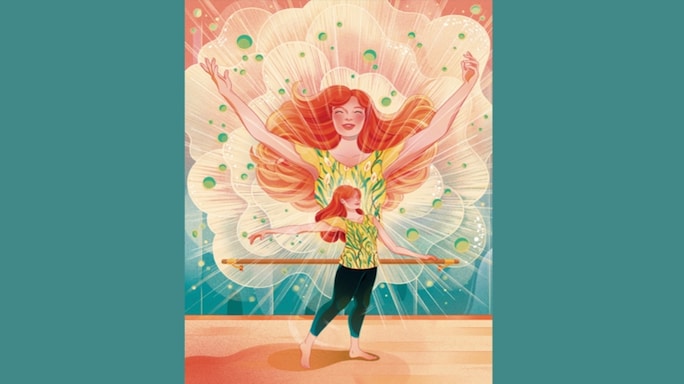

illustrations by Aliya Ghare

illustrations by Aliya Ghare

Wearing all black and sitting on a tufted white ottoman in her sunlit living room, Sarah Robichaud is teaching a routine inspired by modern ballet to 80 students on Zoom. The Bolshoi-trained dancer spreads her arms wide in exaggerated movements to a slow cover of The Proclaimers’ 'I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles)' as her students get into the groove.

“We’re just going to start with a gentle, gentle sway, back and forth,” Robichaud says to the group. “I want you to think that there’s a thread attached to your wrist and someone’s pulling that thread from side to side.”

Many of her students are seated as well. More than half of them have Parkinson’s disease and typically movement can be difficult, but when they try to mirror her fluid and graceful movements, a look of ease comes over them.

Growing evidence shows that dancing can boost brain health and help manage symptoms of neurocognitive and movement disorders, including Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis (MS), Alzheimer’s, dementia and brain injury. For example, a 2021 York University study showed that weekly dance training improved motor function and daily living for those with mild to moderate Parkinson’s. This piggybacks on other findings that show how activities that target balance, coordination, flexibility, creativity and memory work can improve Parkinson’s symptoms.

Robichaud started Dancing with Parkinson’s in 2007 as a way to give back to her community. A few years later, her grandfather was diagnosed with the disease. Robichaud was able to dance with him in his long-term care home until his final days.

“The compassion and care that I have for our dancers is that they’re all my grandfather,” she says.

Recently, one of her students, a man in his 50s who had been adamant that dancing wasn’t for him, said that he now has more dexterity in his hands and generally moves more freely.

“I can’t deny how this is changing my life,” he told her.

So what is it about dance that’s different from a brisk walk or other aerobic exercises?

Dance as Medicine

Helena Blumen, a cognitive scientist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, says the intricate mental multitasking that dance requires engages various parts of the brain at the same time, which can lead to the strengthening of neural connections across different regions. Basically, dancing requires more brain power than simpler repetitive exercises.

“It’s socially demanding, cognitively demanding and physically demanding,” she says.

Anyone who’s ever felt the irresistible urge to sway to a favourite song knows that combining music and movement can lift your mood and melt away stress. But there’s a lot more happening in your brain when you’re trying to follow even the easiest choreography.

“In dance, we have to learn patterns; we have to think symmetrically and asymmetrically; we have to remember sequences,” says David Leventhal, program director at the Mark Morris Dance for PD program, where Robichaud trained.

The effect extends beyond dance class to the real world. Tasks like navigating the kitchen or walking to the bus stop can become more attainable if they are regarded as choreography.

While scientists are still learning how the mechanisms of dancing work in the brain, a clearer picture is beginning to emerge. In 2018, researchers at Otto von Guericke University in Magdeburg, Germany, did MRI scans of older adults who had participated in one of two programs over a six-month period. One group practiced dance and the other did a traditional exercise program with cycling and strength training.

While both groups improved their level of physical fitness, the dancers grew more white and grey matter in the parts of the brain responsible for cognitive processes, such as working memory, attention and high-level thinking. Both white and grey matter typically decline as we get older, making communication in the brain lag and certain cognitive tasks, such as multitasking and problem-solving, tougher.

Together, the researchers hypothesize, these brain changes contribute to more neuroplasticity, which is the brain’s ability to form new connections and pathways. Imagine your brain is like a city with loads of roads and pathways. Brain plasticity is akin to the city’s ability to build new roads, repair old ones or even change the direction of traffic based on how often the routes are used and what the city needs.

So just as cities adapt and change over time to meet the needs of their residents, our brains can reshape and adjust based on our experiences and learning. What’s more, the dance group showed an increase in blood plasma BDNF, a protein that plays a crucial role in developing brain plasticity.

In a 2022 study, Blumen and other researchers from Albert Einstein College of Medicine found that social ballroom dancing was associated with reduced atrophy in the hippocampus—a brain region that is key to memory functioning and is particularly affected by Alzheimer’s disease. The dancers were compared with other adults over age 65 who walked on a treadmill. In other words, the dancers’ memory centre isn’t shrinking as quickly, improving their overall quality of life and potentially reducing the risk of dementia.

Similar studies have shown the benefits of dance for people with conditions ranging from MS and Huntington’s disease to autism and depression. Dance therapy might even help people with brain injuries. A Finnish study of people with severe traumatic brain injury showed that dance-based rehabilitation might improve mobility, cognition and overall well-being.

Dance as Body Acceptance

In addition to the physical and neurological benefits, dance can also help people accept what their bodies can and can’t do, making it easier to live with the diseases they have.

“Dance is about befriending the body,” says Erica Hornthal, a Chicago-based dance and movement therapist and author of Body Aware: Rediscover Your Mind-Body Connection, Stop Feeling Stuck, and Improve Your Mental Health With Simple Movement Practices. Rather than trying to control or “fix” our bodies, dance helps us to meet ourselves where we are, she says.

Dawnia Baynes, 44, was diagnosed with MS in 2006 after her body went numb from the chest down. Today, her hands are still numb, and she suffers from severe muscle tightness and balance issues, which make standing and walking difficult. She recently joined an online dance program for people with MS offered by the University of Florida. Not only has it improved her coordination and range of motion, it has also helped her overcome her fear of being judged for how she moves, in the class and out in the world.

“To see other people moving like I’m moving,” she says, “and know that I don’t have to be professional and super technical in my dancing or make sure my leg lifts this way—it made me comfortable with where I am right now.”

Dance as Community

Dancing with others makes people feel less different, and it helps combat the loneliness and isolation of living with a chronic illness. Allowing those broader connections is one of the reasons that programs initially intended only for people with Parkinson’s and MS have opened up to everyone.

For many people, Leventhal says, dance has become vital to their quality of life. “They’ve come to rely on it in a way that it is an essential part of their Parkinson’s management. It’s not an extra thing that they do because they like to do it,” he says. Since he started teaching more than 22 years ago, the Dance for PD model has been adopted by 300 communities, in 28 countries around the world. Some, including India and South Korea, have incorporated their own cultural dance styles into the class model.

Still, researchers say they’re only scratching the surface of understanding how dance can be used therapeutically. Larger studies are needed to confirm the findings of the smaller trials that have been done so far. Additional studies are also needed to pinpoint the most effective types of dance movements and the optimal length and frequency of classes. It’s also unclear who, in terms of age or disease progression, would benefit most.

Those who aren’t drawn to dance might want to try doing other brain-stimulating physical activities, such as tai chi or yoga, says Notger Müller, a health sciences professor at the University of Potsdam who co-authored the study at Otto von Guericke University. And for people who are timid about dancing in front of others, online classes make it easy to dance at home—like no one is watching. (Many Zoom participants leave their cameras off.)

Robichaud’s mission is to create a sense of community—so much so that she sometimes takes her Dancing with Parkinson’s program on the road and teaches the class from dancers’ homes. Wherever she teaches, her message is one of hope: “We want you to feel joyful, to get more involved in your community, to explore the limitless possibilities for the rest of your life,” she says.