- HOME

- /

- Health & Wellness

- /

- Health

- /

Diabetes: What's New and What's Next

Diabetes is an international health emergency ... but here’s the good news: Amazing breakthroughs offer winning strategies for diabetics today. Here are six that are already here or on the way.

Image Credit: ©WAYHOME studio/Shutterstock; Illustrations by Harry Campbell

Image Credit: ©WAYHOME studio/Shutterstock; Illustrations by Harry Campbell

It’s no exaggeration to say that diabetes is an international health emergency. According to the International Diabetes Federation, as of 2017, 425 million adults (aged 20 to 79 years) in the world have some form of the disease; experts estimate that this number could go up to 629 million people by 2045. In the same year, India alone reported 7,29,46,400 diabetes cases.

Type 1 diabetes, caused by an immune system attack on the pancreas, usually strikes younger people and follows them throughout their lives. Type 2 diabetes is more common and caused by resistance to the hormone insulin, which tells the body to absorb blood sugar. According to Dr Ambrish Mithal, chairman, division of endocrinology and diabetes, Medanta -- The Medicity, Gurugram, “Type 2 diabetes cases are increasing rapidly and they are now occurring at a younger age. The figures are staggering. In Delhi and Chennai 20 per cent of people get the disease by age 40. About 30 to 40 per cent have type 2 by age 60.”

But here’s the good news: Over just the past few years, a remarkable number of diabetes treatments, from medication to surgical solutions to high-tech devices, have shown promise. It’s too soon to declare victory, but these breakthroughs have given people with diabetes something sweet: Winning strategies for today and considerable hope for the future. Here are six that are already here or on the way.

FOR PREDIABETES

Prevention Programmes

WHAT IT IS

As recently as last year, Pamela Hancock, 67, of Northwich, England, wouldn’t think twice about eating a dozen or more lard-roasted potatoes as part of her dinner or a hulking slab of chocolate cake for dessert. “I knew about healthy eating, but as the years have gone by, the plates got piled up more and more,” Hancock says.

Six months ago, her doctor worried that Hancock’s excess weight and high blood pressure put her at risk of diabetes, so he asked her to join the National Health Service’s Diabetes Prevention Programme (NHS DPP), that aims to help people with prediabetes eat healthier, exercise more often and drop enough weight to slash their risk of having their disease progress to type 2 diabetes. “It helped me to lose a lot of weight---just over two stones [12.7 kg]---and I’m still losing weight,” Hancock says. “What we’ve been watching is the portion control on the plate. Now I have three to four roast potatoes. And I’m eating a lot less of the chocolate cake, and not as often.”

HOW IT WORKS

The Diabetes Prevention Programme in the UK was modelled after landmark diabetes prevention studies from the US, which set goals for people at risk of developing type 2 diabetes: A modest seven per cent weight loss over nine months and a minimum of 150 minutes of exercise each week.

Dr V. Mohan, chairman and chief diabetologist at Dr Mohan’s Diabetes Specialities Centre in Chennai, agrees that an intensive diet, exercise and lifestyle modification methods are solid preventives. “In the Diabetes Community Lifestyle Improvement (D-CLIP) study, we showed that up to a third of people with prediabetes can avoid developing diabetes. This is an important finding given that there are around 80 million people with prediabetes in India and the fact that the conversion from prediabetes to diabetes occurs much more rapidly in Indians,” he says.

Managing portion sizes and reducing fat are key. “Fat cells, particularly in the abdomen, release hormones that increase risk for diabetes,” says David Nathan, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and the director of the Diabetes Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, USA. “And it takes only a small amount of weight loss to lower risk. We found that dropping just two pounds [less than one kg] lowers your odds for diabetes over three years by about 16 per cent.” “Weight reduction is the single-most powerful technique to prevent or delay diabetes,” adds Mithal.

Metformin

WHAT IT IS

Metformin has been research-proven to reduce the incidence of type 2 diabetes among people with impaired glucose tolerance. It helps reduce insulin resistance. “This is the most commonly used drug to treat type 2 diabetics who can tolerate it (the drug has gastrointestinal side effects). It is also prescribed for people with prediabetes who are not responding to lifestyle measures,” says Mithal.

HOW IT WORKS

Metformin reduces blood sugar by lowering the amount of sugar coming from the liver. A 2017 Georgetown University, review showed that it cuts the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 18 per cent over 15 years.

FOR TYPE 2 DIABETES

Metabolic Surgery

WHAT IT IS

Rerouting the digestive system with gastric bypass surgery (so called because it creates a smaller stomach and bypasses part of the small intestine) or with a sleeve gastrectomy (which reduces the size of the stomach by about 80 per cent) is a drastic diabetes solution. After all, it is major surgery, with small but real risks for complications, such as infections, bleeding and gastrointestinal problems. It’s also not a stand-alone solution. “Metabolic or bariatric surgery is offered to people with diabetes who are severely obese and where other lifestyle measures have failed,” Mithal warns.

Such was the case with 13-year-old Amit Gupta* from Bengaluru, when he was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. He spent hours playing tennis and tried countless diets, yet his weight refused to budge from 108 kg. With blood sugar levels over 500, well beyond normal levels, his body was running on borrowed time. For five years his doctors worked hard to reign in the soaring blood sugar levels with little success. His sugar levels rarely dropped below 250. Eventually, doctors recommended bariatric surgery. Amit was 19 years old at the time. Soon after, he lost 37 kgs and his sugar levels have been normal ever since.

HOW IT WORKS

Reducing the size of the stomach makes it easier for patients to stick with smaller portions---but patients are also strongly urged to follow a healthy diet. New research is showing that the surgery produces safe, long-lasting benefits, particularly in people with recently diagnosed diabetes.

Research has shown that people who have surgery within five years of being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes have a 70 to 75 per cent chance of a complete remission. “Remission means that sugar levels become normal, glycosylated haemoglobin levels (HbA1C---the measure of three month’s control of diabetes) also become normal and all this is achieved without the use of any anti-diabetic drug. Remission of diabetes does occur if these surgeries are done early in the natural history of diabetes, particularly in those who are on small doses of insulin or only on oral anti-diabetic drugs. However, in our experience, most patients still require small doses of oral anti-diabetic drugs and hence true remission is rare in our series of bariatric surgery patients,” says Mohan.

In 2016, more than 45 medical organizations endorsed bariatric surgery for people with moderate to severe obesity and diabetes. “However, the surgery does have some morbidity and a small mortality rate as well. Hence it has to be done by an experienced surgeon with a full team of specialists, a diabetologist or endocrinologist along with a psychologist, dietician and others in order to ensure the best results,” adds Mohan. For many people, the first steps in battling diabetes should be lifestyle changes, followed by medication as required.

(*Name changed upon request)

Double-Duty Drugs

WHAT THEY ARE

Tablets that combine two diabetes drugs into one medication have become more commonplace. The availability of particular drugs varies by country, but a number of combination diabetes medication are widely available. The trend gives patients fewer tablets to swallow at each sitting, making it easier to follow doctors’ orders.

In the past many combination drugs were available in India but recently the government has clamped down on fixed dose combination drugs (FDCs), regulating their manufacturing and sale, and also banning over 328 drugs, including the combination diabetes drug Gluconorm PG.

In a largely unregulated market like India, there are concerns about the efficacy of these drugs when used in combination. “Combination diabetes medication poses its own challenges---their bioavailability and the need to take certain medicines before or after food, for example. What happens when you combine them?” asks Mohan.

HOW THEY WORK

Two-in-one treatment is quickly becoming standard for people with type 2 diabetes. Up to 43 per cent of them now take two or more diabetes drugs, according to a recent international study of the medical treatments of 70,657 people with type 2 diabetes. They may help diabetes patients live healthier lives. “There are well-known studies showing that if you can reduce the number of medications that patients have to take, then you improve their adherence,” Lawrence says.

FOR TYPE 1 DIABETES

The ‘Artificial Pancreas’

WHAT IT IS

When Anthony Tudela, 44, of Vizille, France, skis, snow- boards or does mountain-bike racing, he’s no longer concerned that the intense physical exertion will lead to drastically low blood sugar, known as hypoglycaemia. Since 2017, he’s worn an experimental type 1 diabetes management device known as the Diabeloop DBLG1 system, which measures his blood sugar levels every five minutes and delivers the required insulin to keep him within target levels. When Tudela plans to physically exert himself or eat something, he inputs the data into the Diabeloop interface system on his mobile phone. The device then adjusts his insulin levels accordingly. It checks his blood sugar levels regularly, so if Tudela over- or under-calculates, he doesn’t suffer the consequences.

“I can take sugar immediately, and 15 minutes later, the sugar level is okay,” says Tudela, who was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at age seven. Before using the device, Tudela’s blood sugar levels were on target only 30 to 40 per cent of the time. His HbA1C levels hovered between 11 and 12 per cent, and he experienced hypos regularly. With the ‘artificial pancreas’, Tudela’s blood sugar levels are on target 76 per cent of the time. His HbA1C levels have dropped to 7.5 per cent, and he doesn’t get hypos anymore, because the device keeps such tight control of his blood sugar levels. “With this machine I feel free---I can live as if I wasn’t diabetic,” Tudela says. “But you have to trust the device. For decades, you got accustomed to the idea that you have to control your disease; you are responsible for it. And all of a sudden, the device is responsible. You have to let it go, and it is not so easy.”

It is important to note that the term ‘artificial pancreas’ can be misleading and it is not, in fact, a replacement for the organ, says Dr Anand Khakhar, senior consultant, liver transplant and hepatobiliary surgery, and director for the liver transplant programme at the Centre for Liver Disease & Transplantation, Apollo Hospitals, Chennai, Hyderabad and Bengaluru. “These devices do not function like a pancreas. It is simply an automatic pump which controls insulin.”

You can’t yet buy an ‘artificial pancreas’ system like Tudela’s experimental one, but that could change soon. Diabeloop is in the process of marketing the DBLG1 system, which could become commercially available in France and other EU countries within a few months. “The reason that these devices haven’t been approved for commercial application and are largely used for research is the fear that these instruments could put a patient’s life at risk in case they are faulty,” says Dr Mohan. However, he agrees that insulin pumps, both basic as well as the more advanced versions, do help to achieve and maintain much better control of diabetes and reduce the fluctuations in sugar levels. They are, however, rather expensive currently.

HOW IT WORKS

This device automatically senses blood sugar levels. It uses a continuous glucose monitor alongside an insulin pump that processes the data to deliver just the right spurts of insulin round the clock. That reduces the need for finger sticks, blood sugar checks, insulin shots and having to programme an insulin pump by hand. “A device such as this should be capable of automatically switching off when blood sugar is low and step up the dose of insulin when it is high. Different models of advanced insulin pumps are available today but these are, strictly speaking, not an artificial pancreas,” cautions Mohan.

“Insulin pumps have no intelligence; they just deliver insulin, according to a programme developed by the endocrinologist,” says Pierre-Yves Benhamou, head of the endocrinology--diabetology department at the Grenoble University Hospital Center in France and member of the Diabeloop medical development team. “The DBLG1 system, developed by Diabeloop, is completely different. The quantity of insulin delivered to the patient adapts all the time according to the blood sugar level of the patient.”

All of the clinical trials thus far have been done on adults with type 1 diabetes, but the next trial will study paediatric patients. The goal is to eventually regulate blood sugar levels and reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia in all type 1 patients.

Islet Cell Transplants

It wasn’t unusual for Richard Lane of Beckenham, England, to regain consciousness in an emergency department after having a hypo-induced coma (a potentially fatal diabetes-related complication where an extremely low glucose level causes unconsciousness). Lane, now 75, was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in 1976, and for most of the years until 2004, he had little to no warning that a hypo was coming on.

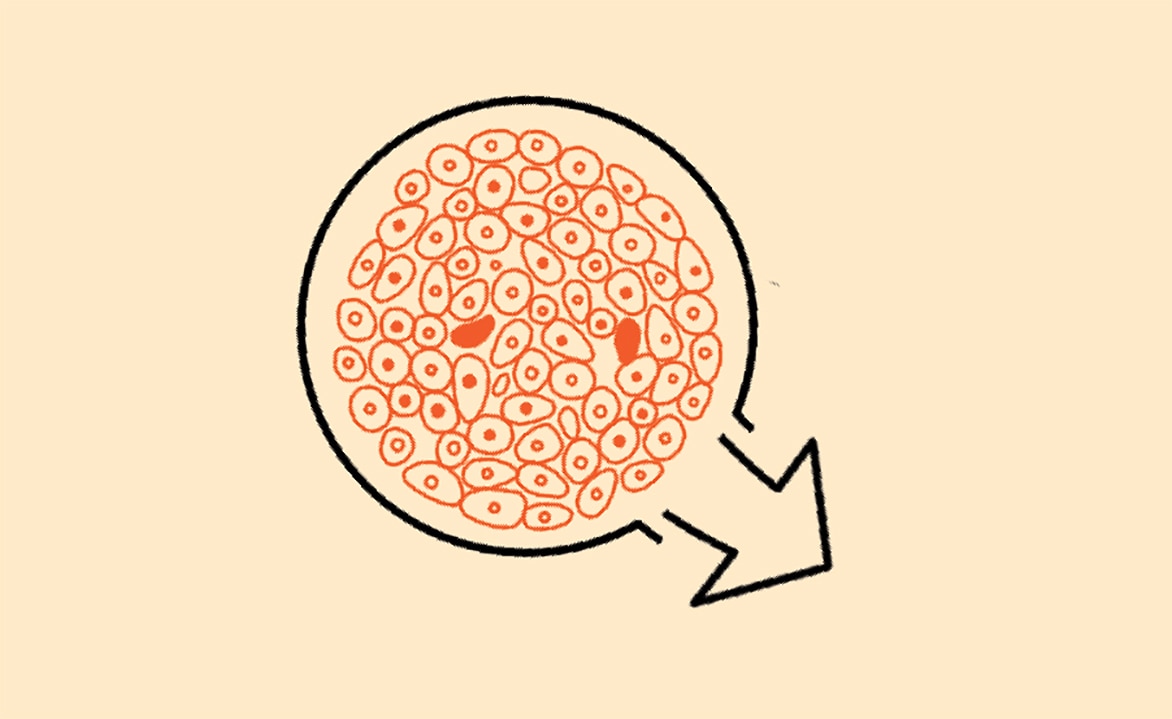

“Life was absolutely awful,” says Lane, the first ambassador of the charity Diabetes UK and its immediate past president. “I’d wake up in many different hospitals. And my wife lived a really difficult life, wondering when I went out of the house whether she was going to get another phone call from the ambulance service.” By 2004, Lane experienced between four and six fairly severe hypos weekly, most with no warning. When his doctor offered him the opportunity to regain warnings of hypos through an experimental treatment called islet cell transplantation, he jumped at the chance. Islet cells in the pancreas make insulin; when they die out, type 1 diabetes results. So wouldn’t transplanting healthy new islet cells fix the problem?

Islet cell transplants are available in many countries, including the UK, Canada, Australia, France, Switzerland, Italy, Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands. “In India, transplants using stem cells and islet cells are being attempted and research is underway. Collaboration with various government and private partners are on; South East Asia’s first islet cell lab will be set up in Chennai by 2020,” says Dr Khakhar.

In a number of countries, this procedure is now government-funded. Lane received three islet cell transplants in 2004 and 2005. Within a few months, he became the first person in the UK with type 1 diabetes to stop taking insulin, as a direct result of the transplants. A year later, he needed to take insulin again, and after a few years, the transplanted islet cells died off. But Lane is grateful for those transplants. “The main purpose of the treatment was not to enable me to come off insulin; it was to actually bring back my warnings of hypos,” Lane says. “I have got my warnings of hypos back. So I’m still benefiting hugely from the treatment.”

HOW THEY WORK

Islet cell transplants aren’t for everyone. “Islet transplantation is only considered if patients have been tried on optimal conventional treatment first,” says professor Paul Johnson, director of the islet transplant programme at the University of Oxford. “They need to have been treated with the best possible modern insulins and insulin pumps, and despite that, still be getting hypoglycaemic unawareness.”

It’s a much less invasive procedure than a whole pancreas transplant: Islet cells are typically injected into the liver via the portal vein where they start to function as they would in the pancreas. (Islet cells aren’t transplanted back into the pancreas, because the risk for complications is fairly high.)

“It isn’t a major operation,” Johnson says. “It’s like having an intravenous drip run through. Nearly all islet transplants in the UK are done in the X-ray department, with the patient still awake, but with a local anaesthetic injection over the liver and some sedation.”

Most patients need two consecutive islet cell transplants to ensure that the procedure is effective and that the islets last. (The cells can last for many years but tend to function for three to five years.) Patients who receive islet cell transplants must take anti-rejection medication immunosuppression) ---which have many side effects---for the rest of their lives.

Many patients are able to stop taking insulin for some period of time: In a recent study, when 48 people whose type 1 diabetes was extremely difficult to control (leading to life-threatening low blood sugar episodes), received islet cell transplants, 52 per cent had healthy blood sugar levels one year later without insulin.

“Even if they require some insulin, an islet transplant can be life-saving in terms of preventing sudden death by undetected hypos,” Johnson says, “and life-improving by helping to prevent complications such as blindness, kidney failure and heart disease resulting from uncontrolled high blood sugar levels.”