- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Classic Reads

- /

Niki Lauda's Duel with Death: The Incredible Comeback story of the Legendary Formula-1 Racer

The accident at Nürburgring should have meant the end of his racing career. Instead it was the beginning of this champion’s greatest triumph

Illustration: Siddhant Jumde

Illustration: Siddhant Jumde

When Marlene Lauda arrived at Cologne airport on the evening of 1 August 1976, she expected to meet her husband, world-champion racing driver Niki Lauda. Lauda was competing in the German Grand Prix at nearby Nürburgring, but Marlene, whose heart hammered even when she watched televised reruns of races, often stayed away from the track. She and Niki were to meet at the airport after the race and fly home to Salzburg.

Lauda was not waiting for her in the airport lounge. Instead, she was met by strangers who broke the bad news: There had been an accident; Niki was in a hospital at Mannheim, 240 kilometres away.

Time blurred, and then she was standing in an intensive care unit looking down at a monstrous mask that bore no resemblance to her husband. The face was brutally burned and swollen to three times normal size; eyes and nose were swallowed up in a balloon of charred flesh. Each frightful gasp from the shrivelled mouth seemed to be a final act.

A doctor led Marlene outside. “Will he live?” she asked.

The doctor shook his head. The exterior burns might be dealt with, but Niki had sucked flame and poisonous gases down through his bronchial passages. Now the scalded lungs were failing. It could only be a matter of hours.

Marlene, waiting, wept through the night. But behind closed doors, Niki Lauda, who sensed the presence of death in the room, refused to die.

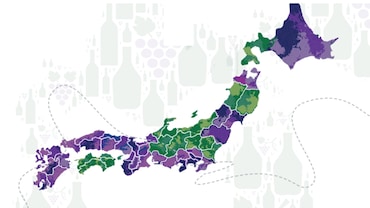

Niki Lauda at the wheel during the 1974 Race of Champions in which he won second place.

Niki Lauda at the wheel during the 1974 Race of Champions in which he won second place.

The day had begun with rain, adding an extra dash of danger to the Nürburgring, widely considered the most dangerous track on the Grand Prix circuit. Lauda had lobbied, unsuccessfully, to have that year’s race moved to another site. Driving a 12-cylinder, 500-horse-power Formula 1 racing car at Nürburgring, he said, was like trying to land a jumbo jet on a grass strip. Each 22-kilometre lap snaked through 176 turns and zoomed over countless slopes. Many drivers agree that there is little room for a car in trouble to run off the track safely.

Even without such a track, Grand Prix racing is a devastating test of men and machines. Every year, drivers, crews and cars—as many as 15 for each team—embark on a 10-month odyssey, staging 17 gruelling races on four continents. During trial heats, only a few seconds separate the winner from the last qualifying car. And of the usual 25 drivers who start each race, only the first six to finish gain points toward the championship—worth millions to the victor.

The investment is staggering—from the cost of a Formula 1 racer (upward of $1,00,000) [around $4,90,000 today] to the toll in lives—for, at straightaway speeds approaching 720 kilometres an hour, the driver is pushing his fragile powerhouse to its outermost limits. Of the 14 drivers who have become World Grand Prix Champions since 1950, four have been killed on the race tracks.

But nothing could dim the ardour of Andreas Nikolaus Lauda, 28, for fast cars. At age 18, Niki, the son of a Viennese businessman, got his grandmother to put up $3,900 [$19,000 today] for a racing mini-Cooper. Four years later, having raced his way up through the ranks, he took out a $1,00,000 bank loan in order to join a British racing team and drive a Formula 1 car. In 1974, Lauda signed on with Enzo Ferrari, the dean of motor racing and president of Italy’s Ferrari works, and that year he finished fourth among Grand Prix drivers.

The following year he captured the championship, and in 1976, going into the German Grand Prix, he had won five of the first nine races.

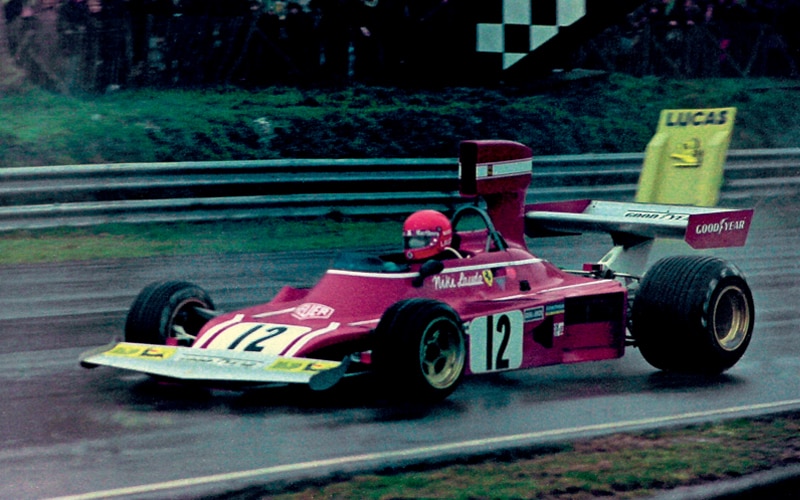

Niki Lauda’s red Ferrari 312T2, engulfed in flames after it crashed and was then hit by a competitor during the Grand Prix Germany in Nürburgring

Niki Lauda’s red Ferrari 312T2, engulfed in flames after it crashed and was then hit by a competitor during the Grand Prix Germany in Nürburgring

Despite the rain, a crowd of 3,00,000 was filling the Nürburgring stands on 1 August, when Lauda began the ritual of final preparation. He stuffed both ears with wax and cotton wool. He pulled on a non-flammable sweater and face mask, zipped his flame-retardant jumpsuit closed and fastened his crash helmet. A few minutes before starting time, the rain stopped and the sun broke through. But Lauda decided to keep treaded ‘wet’ tires on his red Ferrari until the track dried.

Although Lauda’s qualifying runs had earned him an upfront starting place, he got off badly. After the first lap, he was in ninth place and pulled into the pits to change to slick, dry-track tires for more speed. That took 60 seconds. Then he came roaring out, leaving swathes of burnt rubber on the pavement, and worked his way up through the gears. Halfway around on the second lap, something happened.

Some say the Ferrari threw a wheel, others that it hit a wet spot; Lauda has no recollection of the moment. But as he came speeding into a rising left turn at 500 kilometres an hour, his car tore loose from the roadway and went flying into the embankment. The gas tanks split open, and the Ferrari careered back to the centre of the track, coming to rest broadside. The first following car swerved left and gave it only a glancing blow. But the next one shot around the curve and, brakes screeching, smashed squarely into the wreckage, setting it ablaze.

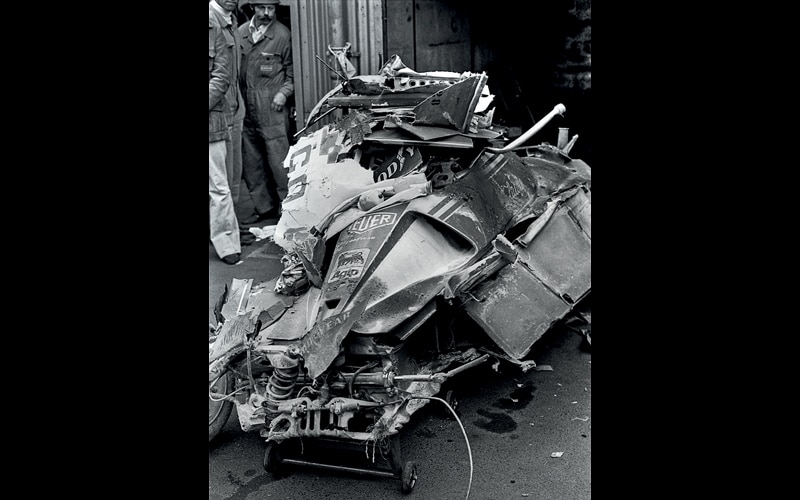

The remains of Lauda’s Ferrari after the crash Photo: Getty Images

The remains of Lauda’s Ferrari after the crash Photo: Getty Images

Trapped in the cockpit by his jammed restraining harness, Lauda was unable to trigger the Ferrari’s fire extinguisher. His helmet had been ripped off, and the flame-retardant face mask was turning black in the intense heat. Other drivers stopped and ran to his aid. One of them, Italian racer Arturo Merzario, dived right into the fire to unbuckle Lauda’s six-point seat belt. Then, stepping on to the front of the car, he seized Lauda by the upper arms and pulled him out of the blazing wreck. Somehow Lauda found the strength to walk away from the inferno. He touched his bloody, blistering face and asked his rescuers, “How do I look?”

“Fine,” they lied.

Then he passed out.

Lauda had been in the flaming ruins of the Ferrari about 45 seconds, inhaling fire and toxic fumes from the burning synthetic parts. As the doctors discovered at Ludwigshafen Hospital, some 144 kilometres away, where he was flown by helicopter, he had suffered second- and third-degree burns on his face and hands, as well as a crushed cheekbone and three fractured ribs.

But the most immediate threat was his deteriorating lungs. That same afternoon, he was transferred to the Mannheim University Clinic, the nearest hospital equipped to deal with pulmonary emergencies.

For the next three days, Lauda hung suspended in a grey void, unable to speak or see, but aware of his wife’s presence, of the respirator, oxygen and tubes that tenuously linked him to life. The doctors were astonished at his tenacity. He was stubborn, they agreed, but he was still dying.

At a certain point, Niki felt that his body was beginning to give up in anticipation of blessed relief from pain. But his brain would not yield. He was determined to survive, and he willed his way back up from darkness. Even though a priest was called in on Tuesday to give him the last rites, he forced himself to concentrate on voices, sounds—any sensation that confirmed his place among the living,

Hour by hour, the darkness receded. By Wednesday night, he was breathing well enough to be taken off the respirator. The next day he insisted on sitting in a chair, and on Friday, sight and voice restored, he put a bandaged hand on Marlene’s arm and walked around the room. From then on, it was Marlene who led him back to life, with love and absolute confidence that he would get well.

The film Rush (2013)—starring Daniel BrÜhl who played Lauda and Chris Hemsworth as Hunt—captured their starkly contrasting personalities, intense competition, and mutual respect, shedding light on a legendary sports rivalry.

The film Rush (2013)—starring Daniel BrÜhl who played Lauda and Chris Hemsworth as Hunt—captured their starkly contrasting personalities, intense competition, and mutual respect, shedding light on a legendary sports rivalry.

That Friday the doctors took him off the critical list, while Lauda continued to work at his recovery. He endured infusions, injections, two complete blood changes and a major skin-grafting operation. The burnt tissue was excised from his face and replaced with strips of skin from his upper thigh.

Then, barely two weeks after his accident, Niki told Marlene that he was going home to prepare for the Italian Grand Prix at Monza on 12 September.

The doctors reluctantly agreed. They told him he required more plastic surgery on his face and that it would be months before he was really well again. But Lauda was ready to get on with his life. The plastic surgery could wait.

“I knew what people would say,” Lauda recalls, “that a man with a face like mine should stay in hiding. But that is not my attitude. I have a talent, a profession. And if it turned out that I couldn’t handle it anymore, the sooner I found out the better.”

Back in salzburg, Niki began a rigorous conditioning regimen. He ran for an hour every day, did uncounted sit-ups and deep knee-bends and, for the first time since the accident, slept without the shadow of death to goad him awake.

Niki Lauda (left) and James Hunt, a British racecar driver and one of Lauda’s toughest competitors. The fierce rivalry and unlikely friendship between Lauda and Hunt defined 1970s Formula 1.

Niki Lauda (left) and James Hunt, a British racecar driver and one of Lauda’s toughest competitors. The fierce rivalry and unlikely friendship between Lauda and Hunt defined 1970s Formula 1.

Three days before the Italian Grand Prix, Ferrari publicly declined to accept responsibility for Lauda’s decision to race again. But Lauda, already at Monza for the qualifying runs, paid no heed; he had a more pressing concern. Coming to a stretch he ought to have taken flat out, he felt his foot, unwilled, lift from the accelerator.

When it happened again, he quit for the day and, as he put it, had a good talk with himself: if he wanted to be a racing driver, he had to be prepared to go the limit.

Six Sundays after the crash at the Nürburgring, Niki drove the circuit at Monza like the Lauda of old. He did not win—he finished fourth—but the huge crowd gave him a rousing ovation. Other athletes had made startling comebacks from severe injury; Lauda had come back from the dead.

But he was to face one more test of courage before the season ended. Having missed two races during his hospitalization and convalescence, Lauda came to the final 1976 race, the Japanese Grand Prix, a bare three points ahead of England’s James Hunt, his nearest rival for the title. One or the other would emerge as overall Grand Prix champion.

On the day of the race, rain and fog shrouded the track at the foot of Mount Fuji. The start was delayed; the drivers debated whether to race at all. Finally, with 55,000 spectators howling for action, they set off on to the wet roadway. Lauda, starting from the second row, drove one lap in blinding spray from the cars ahead, then pulled off the track. He had calculated the odds, carefully and without emotion, and found them too long, too dangerous. He withdrew from the race.

Niki Lauda, at the 2014 annual Golden Globe Awards, where the film Rush, based on his incredible comeback story, won the award for Best Motion Picture (Drama) and Best Supporting Actor (Daniel Brühl)

Niki Lauda, at the 2014 annual Golden Globe Awards, where the film Rush, based on his incredible comeback story, won the award for Best Motion Picture (Drama) and Best Supporting Actor (Daniel Brühl)

Predictably, there were those who proclaimed that the Nürburgring had finished Lauda. But James Hunt, who stayed and won the championship, understood that Lauda’s withdrawal at Fuji was a high order of bravery. “You can beat Lauda if you have a very good day,” he said. “To break him is out of the question. He will be back.”

He was right. Lauda began the 1977 season by winning the South African Grand Prix, the third race of that year. And he kept winning. When the procession of Grand Prix cars and drivers moved to Japan to close out the season, Lauda was not among them, this time because he did not need to be. He had clinched the World Driving Championship at the US Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, N.Y., three races before the season’s end.

The man whose indomitable will denied death had come all the way back.

Editor’s Note:

Niki Lauda continued to compete at the highest level until 1979, when he took a break to start his own airline, Lauda Air, returning to the track off and on to help fund its growth. He officially gave up racing for good in 1985, by which time he had built a legendary status in the world of professional racing. Lauda went on to serve the sport as a television commentator, adviser for Ferrari, board member of Mercedes AMG Powertrains, non-executive chairman of the Mercedes Formula 1 team, and special adviser to the Board of Daimler AG. Soon after his airline closed in 2013, Lauda’s health began to decline. He underwent multiple transplant surgeries, including one in 2018 for a lung damaged in the 1976 crash. In May 2019, he passed away in hospital, at age 70.

First published in Reader's Digest February 1978