Between a Rock and a Hard Place

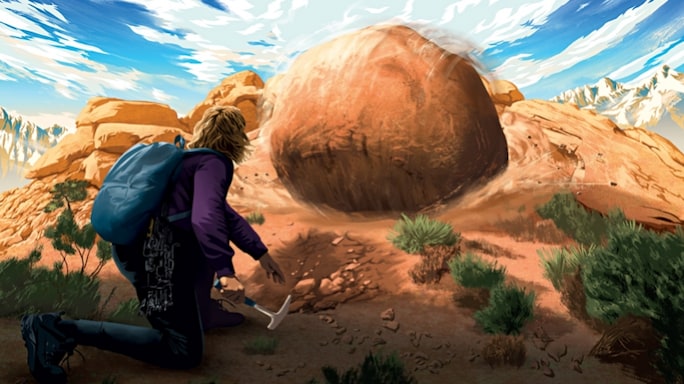

Pinned by a giant boulder, a hiker had two choices: panic or gut it out. He did both.

illustrations by Pete Lloyd

illustrations by Pete Lloyd

The Inyo Mountains rose dusty and jagged into a perfect blue sky as Kevin DePaolo and Josh Nelson set off across the desert range.

That corner of eastern California was DePaolo’s favourite part of the country, which was saying something, because the 26-year-old had visited nearly every inch of the United States.

Wiry and strong, with blond shoulder-length hair and an earnest way of speaking, the New York–born DePaolo had spent his time since college in search of adventure, impatient for life experiences. For the last few years he’d been a nomad, living out of a tricked-out van he’d christened Vanessa, while doing odd jobs and remote data analyst work from the road.

He’d been up to Alaska and down to Florida, and crisscrossed the states in between. But something about that part of California, where you could find both outdoor thrills and a little solitude amid the ancient mountains, had always seemed special to him.

Part of the draw was the friends he’d made there, especially Josh Nelson. The two had met a few years earlier in a coffee shop in the town of Bishop. The men had bonded instantly. In DePaolo, Nelson saw a kindred spirit, someone who wanted “every ounce of adventure he could get.” And in the 38-year-old Nelson, DePaolo found an older brother figure—someone who taught him everything from rock climbing skills to where to find deposits of crystals out in the mountains.

That morning last December, DePaolo was back in Bishop. He’d found a perfect spot to go rock hounding—searching for crystals and minerals—and now he wanted to show Nelson his discovery.

Nelson was feeling under the weather, just getting over a cold, so DePaolo shouldered most of the load—shovels, pickaxes—as they walked through sandy gullies and scrambled over boulders. After about an hour and a half, they arrived at a rocky hillside spot. It was just as DePaolo had said—a deposit of “cool rocks” buried just in front of a pair of enormous boulders.

For almost two hours the friends happily dug in the sand side by side, pulling out rocks of all shapes and sizes. At around 3 p.m., Nelson stepped aside to rest and enjoy the perfect 65-degree temperature while DePaolo continued to kneel, working away with a small scraper, in the large hole they had dug in the sand. The boulder closest to him was slightly uphill, but it had a look of permanence to it, as if it hadn’t budged in millennia and wouldn’t move any time soon. But here he was wrong. Whatever equilibrium the enormous stone had found over the years was slowly being shifted, grain of sand by grain of sand, as DePaolo scraped away beneath it.

DePaolo sat up for a moment and turned away as he caught his breath. That’s when he heard Nelson yell, “Look out, Kevo!”

DePaolo turned back. And in that instant, the boulder lurched toward him, and rolled, crashing into him like a semitruck and crushing his legs into the sand.

With Depaolo now pinned to the ground up to his thighs, Nelson ran to grab the pickax and wedged it between the rock and the ground to keep it from rolling any farther, as DePaolo bellowed in agony. The pain was extraordinary. It seemed to short-circuit his brain, the world becoming strange and dreamlike, while his body went into shock, adrenaline pumping through his veins.

Am I really gonna die like this? he wondered. He turned to Nelson and saw on his friend’s face a look of fear that made him lose whatever composure he had left.

“You gotta get this thing off of me, man!” he yelled.

“I’m trying, I’m trying!” said Nelson.

The boulder was massive, had to be between 2,500 and 4,500 kilos, and Nelson strained against it. He gave three enormous heaves, and on the final push he was able to rock the boulder ever so slightly. It was enough that DePaolo could feel his left leg—numb and limp—was almost free, only held in place by the material of his pants. He grabbed the scraper and began tearing through his pants before pulling his leg out from under the boulder.

With one leg freed, he could angle his body out of the path of the boulder in case it came tumbling any farther. But his right leg was completely, irrevocably trapped. And his left leg had been blown open, the skin torn from the back of his thigh to his groin, with exposed muscles and arteries gleaming nauseatingly in the sun.

As a veteran climber, Nelson had been in a few emergency situations before, but he’d never experienced anything like this. He could see that his friend’s exposed femoral artery was damaged and oozing blood. He was terrified that DePaolo would bleed out.

Nelson double-wrapped the leg with a T-shirt and his sweater, and applied pressure. He then tried his cellphone. Miraculously, despite being in the middle of nowhere, he got a signal. He called 911 and told a dispatcher where they were. The dispatcher stayed on speakerphone with them, urging DePaolo to stay calm.

Nelson started digging beneath the boulder, hoping to shift it enough to free his friend. But DePaolo felt the boulder shift above him, bearing down on his leg even harder. The dispatcher yelled at them not to dig any further. There was no escaping. The only thing to do was stay put and hope that a rescue team could reach them.

DePaolo kept asking his friend, “Am I going to die?”

Nelson shook his head. “You’re not going to die, man.” He couldn’t tell if he was convincing or not. He didn’t fully know if he believed it himself. But he knew that staying calm was the only way his friend was going to make it out alive.

Cpl. Victor Lawson of the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office was supposed to be enjoying a day off. But when you’re the search and rescue coordinator in a part of the country where hikers and mountain climbers often get into trouble, days off are never guaranteed. Lawson, a longtime climber, leads a crew of highly skilled volunteers, many of them ‘dirtbag’ climbers, who spend every possible waking moment in the mountains, and who want to put their experience and abilities to good use.

When he got the call from dispatch, he jumped on the computer to find DePaolo’s whereabouts, using his mapping software. The two hikers were miles from the nearest road, too far for his team to carry DePaulo. He would need to be hoisted out in a helicopter.

The Inyo County Sheriff’s Office doesn’t have its own aircraft, but over the years has developed relationships with a number of nearby organizations that do. Lawson’s first call was to Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, but as bad luck would have it, they were repairing their helicopter that day. The next call was to the California Highway Patrol and its inland division air operations, but, unusually, they weren’t available either.

Lawson put out a call for the rescue team to meet at the Posse Hut—the garage filled with gear where his team planned their missions. As he drove there, he racked his brain. It was now 3:15 p.m., but in the dead of winter it wouldn’t be light for long. Who was nearby who could bring a helicopter out into the mountains and had the capability to hoist a person out in the dark? Any kind of intense rescue mission would take hours, and Nelson and DePaolo were miles off track, in steep, rocky terrain that was difficult to reach. And the dispatcher on the phone had made it clear: DePaolo needed help soon or he would die.

On the side of the mountain, the hours passed slowly. The boulder hadn’t just crushed DePaolo, it had knocked over almost all the water they’d been carrying. That left them with just about one cup of water, which the two men rationed carefully as the hours passed.

DePaolo was wavering between moments of calm and moments of absolute panic. The two men would sit in silence for minutes at a time, DePaolo listening to the sound of the wind and trying to work himself into a Zen-like state, before the reality of the situation would force its way in and he’d scream out again.

Occasionally Nelson would walk a few steps away to confer with the dispatcher on the phone, but whenever he was out of sight DePaolo would yell for his friend to return. At one point he asked for Nelson’s hand. He squeezed it as hard as he could, then bit it—the crazed act of someone in desperate pain.

At around 4:30 p.m., as the sun was setting, the pair heard the distant whir of a helicopter. It came closer, and soon they could see its lights swooping over them. DePaolo’s heart leaped. They’re going to save me, he thought.

The helicopter was from the central division of the California Highway Patrol, which had called Lawson, saying they were available. They flew a reconnaissance flight over the area, sighted the two men, then headed to the trailhead where they would pick up some of the rescuers, who were still driving toward the mountain.

But the two men didn’t know any of that when the aircraft circled and then flew off again, leaving them alone and, once again, in the silence. It felt to DePaolo as though his chance to be rescued had disappeared over the hills.

Night comes fast in that part of the country in December, and temperatures swing wildly in the desert. As the sun went down, temperatures plunged to near freezing. DePaolo began to shiver, every spasm sending an excruciating current of pain through his body. Nelson gathered all the clothing he’d brought in his backpack, rain gear and sweaters, and piled them onto his friend. Then he collected wood and built a small fire, keeping it stoked while the two of them waited under the black, starless sky.

DePaolo focussed on the glow of the fire, keeping his mind on that little patch of light amid the infinite darkness. At one point, DePaolo asked Nelson to call his mom. If he was going to die, he wanted to speak to her one last time. Nelson refused. “You’re not dying on my watch,” he said.

At about 8 p.m., five hours into their ordeal, DePaolo looked up to the hills and saw, glowing in the distance, the beams of headlamps from the search and rescue team, descending to meet them.

The first pair of rescuers had come by foot, driving to the closest spot they could find and then hiking in. With their enormous packs and heavy tools, making their way over the steep terrain in the darkness was treacherous. Each hill they crested presented them with a new predicament: Try to navigate huge boulder fields, or trudge through loose sand?

Moments later, the next pair of rescuers, the ones who had rendezvoused with the helicopter, showed up. The pilot could only find a landing spot about a kilometer away from the site, so they arrived from the opposite direction, facing similar difficult hiking conditions.

Finally seeing his rescuers face to face allowed DePaolo to relax, if just a bit. The team took stock of the situation. An EMT took DePaolo’s vitals, attaching a pulse oximeter to his finger. Despite the incredible damage to his legs, he was stable. Nelson’s rudimentary first aid had done its job.

Meanwhile, the other rescuers were working with purpose. One of the men positioned a Hi-Lift jack, a tool used to lift off-road vehicles, under the boulder. Others drilled into the rock, pounding a bolt into the stone with a rock hammer and attaching a carabiner, which they then attached to a rope-and-pulley system tethered to a large boulder slightly down the hill.

In careful coordination, with two other men holding DePaolo under his armpits, the rescuers used the pulley and the jack to inch the rock off his leg. DePaolo could feel the pressure lessening. He watched in wonder and terror as the boulder rose upward, thinking that one wrong move and he would be crushed. The rescuers tugged him by his armpits, trying to free him, but his ankle was still caught.

“Is your foot free?” they asked.

“No, no!” yelled DePaolo.

Finally, on the third heave—after he’d been trapped for five and a half hours—they managed to pull his leg out from under the boulder.

The rescuers transferred DePaolo to a light stretcher called a litter, and he lay there, still in agony. He realized that he hadn’t thought beyond this moment. He had imagined that once he was out from under the boulder, everything would be fine. But that was not the case.

The rescuers patched him up and tried to keep him as comfortable as possible. Then they delivered more bad news: It was too dangerous to take him off the mountain in the dark. They were staying put for the night.

Back at the Posse Hut, Victor Lawson had not given up on getting DePaolo off the mountain that night. The best bet was by helicopter, but the helicopter crew that had transported the rescuers didn’t have the training for a nighttime rescue at a high altitude, nor did anyone else he contacted. But he’d put in a call to the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services. And they in turn had called the Naval Air Station Leemore, about 160 km away. The copter crew there was willing to try the dangerous maneuver.

Just after midnight, DePaolo once again heard the sound of helicopter blades whirring. The aircraft hovered above them, the force of its rotors spraying DePaolo with small rocks and debris. Then, like something out of a movie, a Navy medic descended on a rope from the sky.

“I’m gonna strap you to me and we’re going to go straight up in the air,” he yelled over the roar. Just like that, the medic clipped DePaolo’s litter to his harness and the two men were rising, DePaolo lying on his back and swinging unsteadily as they rose 10, 20, 30, 40 feet in the air.

Before he could freak out, rescuers aboard the helicopter hauled him in. And then he was off, the aircraft veering over the mountains toward the hospital in Fresno. There, doctors presented him with a good news/bad news scenario. First the bad: He’d broken his pelvis in two places. He had a lot of dead tissue in his leg from where the boulder had struck him, and that tissue needed to be removed. And he had so badly damaged his femoral artery that it would need emergency surgery. The good news: They were hopeful he’d recover.

Kevin DePaolo celebrated Christmas 2023 recovering in the hospital. Photo: Kevin DePaolo

Kevin DePaolo celebrated Christmas 2023 recovering in the hospital. Photo: Kevin DePaolo

After several hours of surgery—plus nine follow-up procedures over the months to remove dead tissue, change the wound vacuum-assisted closure and add skin grafts—and months of rehab, DePaolo was healing, and his doctors expected a complete recovery. With the road ahead looking brighter, he looked back upon that day not with anxiety, but, incongruously, with a profound gratitude. He thought about his friend Josh Nelson. They spoke on the phone just about every day in the aftermath of the accident.

“I told him I love him, that I’m so thankful for him,” says DePaolo. He thought of the search and rescue team, who were inspiring in their skill and toughness. He thought about the helicopter pilot, the doctors and nurses, all these people who had used their abilities and knowledge and care to save him when he couldn’t save himself.

It wasn’t just that he was grateful to them—he wanted to emulate them. Throughout his early 20s, as he travelled the country in search of adventure, he’d also been searching for something else. “I’ve been looking for a kind of purpose in my life,” he says. Now he knew he wanted to give back, like them. Maybe as a firefighter? An EMT? He wasn’t sure, exactly, but the path forward seemed clearer than it ever had. Before any of that, though, he needed to heal physically and spiritually. And to do that, he knew he needed to get back into nature.

One day in late March, just three months after the accident that nearly killed him, DePaolo found himself out in the California wilderness once again. The trail he’d chosen was at Millerton Lake near Fresno, where he’d been recovering and going to physical therapy. It was an easy 5-km loop up Pincushion Mountain, not much more than a hill, really, by his old standards. As he walked, though, his heart pounded and his lungs ached. He could feel every individual muscle in both damaged legs straining.

At one point, halfway through, he had a sudden fear: Have I made a commitment my body can’t actually handle? Then he took another step. Then another. He would go slow, but he would keep going.