- HOME

- /

- Personality

- /

The First Lady of Mental Health

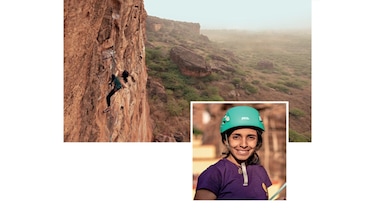

Even at 98, Sarada Menon, India’s first woman psychiatrist, is easing the pain of our mental anguish

Photo courtesy: sarada Menon

Photo courtesy: sarada Menon

Sarada Menon chortles heartily. The 98-year-old is stumped by the question: How many patients has she treated in her long and storied career in psychiatry? “That’s too much to ask, I don’t know,” she says. At least 1,000? “Yes, yes,” she concedes.

Other numbers are easier to pin down. The number of women psychiatrists in India before her: zero. The languages she speaks fluently: four. Her current enthusiasm levels: infinite. She’s received a Padma Bhushan, built and led institutions, worked on prison reform and in flood-prone districts. She has researched, rehabilitated, taught, treated; and packed a bursting resume ever since she finished her MBBS in 1947.

Menon is speaking with me over Skype from her home in Chennai where she still practises, seeing patients daily online. Bespectacled, and quick to smile, she wears her sari crisply and her pioneering status lightly. “I went from day to day, doing what I had to do. I didn’t think about other things,” she says. “How to better the effects of our treatments, was my only goal. I never bothered about anything else.”

Born in Mangalore in 1923, Menon was the eighth of 11 children. Her birth precipitated the usual hand-wringing that followed the arrival of a girl. Six girls had already come before her (“everybody must have got tired”), then a boy (“they were very happy”). So, when her sisters returned from school the day she was born, their grandmother reported the news dismissively. “‘Ha, a girl’—that was her reply,” says Menon, with a deadpan imitation. “Those days, girls were not very popular.”

Menon was educated in Madras, first at the Women’s Christian College and then at Madras Medical College. Her mother died when she was 18, and though her family opposed her desire to study further, the pushback was not serious, or at least didn’t seriously get in the way. “Medicine, they said, is unnecessarily long study,” she says. “At every stage, there was some opposition, [but] somehow, I managed. My parents helped me, even though they didn’t like my joining medical college.”

Menon at her convocation ceremony in 1953 after earning her master’s degree in general medicine.

Menon at her convocation ceremony in 1953 after earning her master’s degree in general medicine.

It cost nothing to earn her degree, and that was a boon in 1942, the year she joined a cohort of about 100 men and 20-odd women in her MBBS. In her final year, an epiphany struck that would kickstart a lifelong journey. The students were taken to visit the local mental hospital where Menon saw patients up close. They were bedraggled, sickly, unkempt in unimaginable ways; laughing, talking and adrift from reality. “I felt very, very sad,” she says. “And I said I must do something about this. Without knowing the cause [of their illnesses] or even completing my degree.”

There were few takers for the specialization then, so scepticism met this decision, too. “For a long time, everybody asked, ‘Why psychiatry?’ But I was very keen.” Mental health was a vague and mysterious sub-field; institutionalization, asylums, lobotomies and shock therapies were common in the middle of the century. Menon did a short stint in London, and then at a general hospital in Andhra Pradesh to get an overall grasp of practice. The All India Institute of Mental Health, which would go on to become NIMHANS—now India’s finest mental-health institute—had just introduced post-graduate courses in 1955. Menon joined in 1957, and spent two years specializing. From 1959, she began practising at what is now called the Institute of Mental Health in Madras, where she took over as head in 1961.

Menon first practised in an era where patients were subdued and sedated, often shackled, and abandoned by their families. In the 1950s, a new drug, chlorpromazine, had just come into the market and it was a water-shed moment in handling psychosis, particularly schizophrenic breaks. “It made all the difference in treatment,” she says. “Symptoms were controlled, the patient became more amenable. Slowly, they would get better, [their] aggression would go, they would understand us.”

Over the years, approaches have evolved, and she underlines how re-habilitation can make a meaningful life possible, that mental illness need not be a life sentence. “Work is a very important part of the treatment,” she says. “You have to study them, give them work that suits them.”

In 1984, after 20 years at the hospital where she led several new initiatives, Menon, along with a group of philanthropists and mental-health professionals, founded the Schizophrenia Research Foundation (SCARF) to treat, research and educate the public. Her years at the hospital had shown her a cross-section of conditions, but schizophrenia, she says, “is the worst type of illness”. It is complicated in its presentation, tough to treat, often with recalcitrant or unsupportive caregivers and patients who were written off. “I thought it was necessary to concentrate on this section of patients,” she says.

Her life spans pre-Independence India and post-liberalization India; she has seen how mental health has gone from neglected sub-field to the centre of the conversation, how practices have improved. “Many new drugs are coming, it’s one specialty with new methods, not only medicines but also psycho-social rehabilitation,” she says.

People, too, have changed. Menon describes how in previous decades, grateful patients would come to invite her to their children’s wedding, stuff the envelope in her hand and in the same breath, sheepishly say: Please don’t attend, if you can. “Some will ask, why was that doctor present at the wedding?” But “there is much less stigma now,” she says. “Patients are coming for treatment. Families are bringing their relatives. After recovery, patients are getting jobs.”

She highlights the importance of related fields—psychology and social work—and the qualities of a good mental-health specialist: “One has to be kind, persistent, patient,” she says. “You have to have a hard core of resilience if you want to do this work. Don’t expect results immediately.”

Menon, holding a book commemorating 35 years of the Schizophrenia Research Foundation (SCARF), the institute she founded in 1984.

Menon, holding a book commemorating 35 years of the Schizophrenia Research Foundation (SCARF), the institute she founded in 1984.

India’s first female psychiatrist is cavalier about the challenges of being a woman doctor, insisting that her gender proved no impediment. Through her work, she met and married a police officer in her forties, a man who was supportive of her career. The regrets are few. For a second, she thinks if she would have done anything different. “Maybe change this or that medicine,” she says. “But nothing other than that.”

At 98, there is little left for her to achieve, but plenty more pleasure to be had from doing the things she loves best. The trick to living well in old age, she says, is to keep at it. “You must try to be as independent as possible,” she says. “You must be grateful that you can do whatever you can do—music, reading, helping people, some activity. You must be active.”

Outside of practice, Menon spends her days reading, doing needlework, and watching television. She is a fiction fiend; from Charles Dickens, Walter Scott and W. M. Thackeray, to Jeffrey Archer and Sidney Sheldon, she admits with a chuckle. And then, there are movies. Her current favourite? A show about another famous 95-year-old woman, living a full and remarkable life: The Crown. Like the Queen, Menon remains a working woman; and there’s a reason she gets up every morning and keeps going. “Because I feel sorry for those who are suffering,” she says. “I want to help them in some way or other. I enjoy doing that.”

Editor's note: Sarada Menon breathed her last on December 5, 2021 at her home in Chennai. She was 98. An inspiration to many, her demise is widely mourned as a great loss to the medical profession, especially in the realm of mental health and its treatment. May her soul rest in peace.