- HOME

- /

- Personality

- /

In Step with Her Self

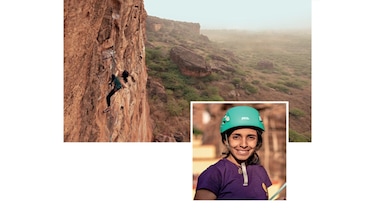

From Kuchipudi and Bharatanatyam to acting and activism, there is little that Mallika Sarabhai has not done in her celebrated and eventful career. This month she speaks to Reader's Digest about her biggest personal and professional milestones and her recently released memoir.

Photo: Yadavan Chandran

Photo: Yadavan Chandran

While others have used the memoir format to take stock of their life and work, the 69-year-old dancer delves deep into the mind by first examining the trials and tribulations of the body in her recently released book In Free Fall: My Experiments with Living. There is much that we can learn from her advocacy of wellness, yoga and mindful living, but the candour with which she describes her struggles is one we should all perhaps emulate. As she spoke to Reader’s Digest, we found that honesty is not a mood for Sarabhai, it is a compulsion.

Any sort of memoir asks for an almost brazen candour from its writer. It seems clear that In Free Fall demanded several honest revelations. Did anything help prepare you?

My life! I thought I had to be truthful and honest and vulnerable. I wanted to be able to help others by showing women and younger people that to be vulnerable isn’t to be weak. If all you show is your beautiful side, without the doubts, people see you as a plastic Bollywood star. Being transparent allows people to trust you. And trust is very important to me in life.

Your father, Vikram Sarabhai, was one of independent India’s foremost space scientists. Your mother, Mrinalini, was a famed Bharatnatyam dancer. How did you interpret their legacy?

I think Papa and Amma were both desperately proud of the children we were. We were never pressured to excel or follow in their paths. They both felt very strongly that they would give us a moral compass, but that my brother Kartikeya and I would have to be navigate life for ourselves. Today, Kartikeya is an environmentalist. I work through the arts, but what do we both work for? We work for the country. We work for the betterment of the nation. What am I trying to do with all my performances, with my book? To achieve exactly the same things that Papa had tried to achieve through the sciences and Amma through the arts. Amma was the first classical dancer to talk about contemporary issues through classical dance. This major breakaway gave a new direction to Indian dance. She talked about dowry deaths and Dalit insecurities, about injustices and the environment. Strangely, both Kartikeya and I are still talking about the same things. I often tell Kartikeya that Papa and Amma are probably having a great giggle, saying, “They thought they would do what they wanted, but in fact, they are doing what we wanted!”

In 1949, your parents set up Darpana, an academy for dance and the performing arts. You write that many of your childhood friends would sign up for classes. Have those levels of enthusiasm still survived?

Oh, yes, and 10 years ago, there was this breakthrough for which I somehow feel a little responsible. I would often see mothers, sitting around, waiting for their daughter’s classes to finish. They’d be gossiping and shelling peas and so on. One day, I don’t know what came into my head. I asked them, “Would you like to dance?” And they said, “At this age? Just look at our bodies.” I said, “I’m not asking you whether you want to be dancers, but would you like to dance?” I could see some of their eyes suddenly sparkle, and so we started a class for them. In the last 12 months, we have had a 60-year-old graduate, a mother graduating at her son’s wedding, mothers and daughters learning in the same class. It’s been amazing!

I also see the way the families react to this. They have never seen this woman. They’ve never seen a woman who is doing something for her own self. She’s never done it in her entire life. And husbands come to me and say, “It’s like being married to a new person.” For me, Indian women, even the most educated and upper-class women, remain so duty-bound, even today. Dance becomes an opportunity for them to unleash something they have always wanted to bring out but have never had the chance to. I feel so blessed!

Would it be fair to say that dance has been the best therapy for you?

Absolutely! I dance when I’m sad. I dance when I’m happy. Not Bharatanatyam, just dance. My body dances. When my children were very young, Shubha Mudgal’s ‘Mann Ke Manjeere’ had just come out. If they saw that I was sad or stressed, one of them would soon go and switch it on. I loved the song so much that no matter what my mood was, I would get up and dance. The oxytocin would, of course, let loose in my head. I would be fine. Music and dance still do that for me.

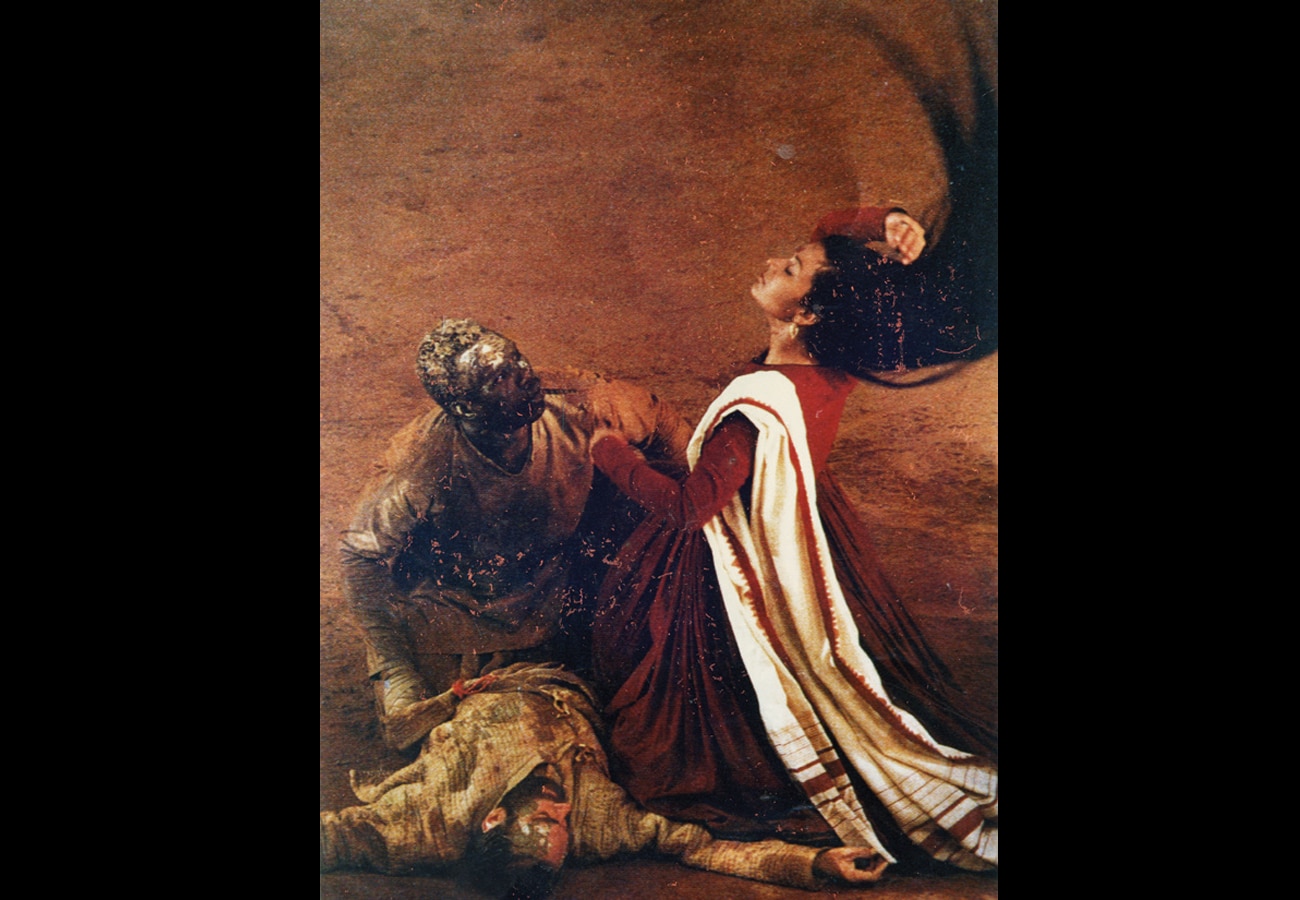

Having played Draupadi in Peter Brook’s iconic production of the Mahabharata for five years, how relevant do you think the epic still is, for India and also its women?

If not interpreted as a series of family fratricides, the Mahabharata will remain relevant for its larger philosophical questions, and for the role both feminism and femininity play in the becoming of its women, of India’s women. Elsewhere, we see the Duryodhanas and Yudhishthiras of today make the same mistakes. The text, I still feel, depicts an endless, forever-true, psychological power struggle.

Sarabhai, as Draupadi, in a scene from Peter Brook’s 1989 production of the Mahabharata: Photo: Gilles Abegg

Sarabhai, as Draupadi, in a scene from Peter Brook’s 1989 production of the Mahabharata: Photo: Gilles Abegg

Peter Brook passed away in July this year. How did you feel?

I wrote so many obituaries. Draupadi was a major turning point in my life. While my mother made me a performer, it was Peter who made me a creator—someone who didn’t care very much about whether she looked or sounded stupid, but someone who had the courage to create her work herself.

Growing up, you battled with anorexia and bulimia at an age when there was no internet. Would awareness have made things simpler or more difficult? Would a diagnosis have helped you?

Today, ‘anorexia’ and ‘bulimia’ are known as mental illnesses, but in my time, these terms never existed. They were things I had to get out of myself. But, no, I don’t think a diagnosis would’ve helped.

You would once ask yourself, Do I want to live fat or die thin? What would your advice be to the people who continue to ask themselves this same thing?

It’s a stupid question, driven by a complete lack of understanding of the possibilities of the body. I took my time in finding it myself, which was fun, but the question is a stupid one. One has to be aware of the medical conditions behind obesity and eating disorders. Apart from a question about looks or aesthetics, people need to be aware that obesity can make your organs do much harder work, compared to when you are fit.

Your book also explores the limits of allopathic medicine. Looking back, was there any one therapy or treatment that opened you up to the idea of more holistic interventions?

When I was 11 years old, I would suffer very, very bad migraines. My grandfather, Ambalal Sarabhai, had a first cousin who ran a flourishing textile business, but was also a homoeopath. He intervened and my migraines just disappeared. So, somewhere, that must have remained imprinted in my mind. The other thing is that all the years I was growing up, and till today, I have been very interested in the possibilities of what the brain can do, and what the body and the brain can do for each other. I have cultivated this interest. Also, the very word ‘alternate’ raises my curiosity. I want to try different things.

To think of one’s body as one’s temple does, of course, have its advantages, but does one also need to be careful of obsession or overemphasis?

The body is not just the external body. There can be an obsession about the external body, but how is one going to be obsessed about the kidney? The body is much more than what you see. One can be obsessive about the way one looks but it’s difficult to be obsessive about how my blood flows.

Does it help to look at addiction and deaddiction through the moral prism of vice and virtue?

It’s fine if you enjoy a drink at the end of your day, but yearning for the fourth or fifth one is not good for your mind or body. Similarly, one rasgolla is fine. It is a problem when I have the 20th one. None of this is a moralistic thing. I have done a million things that society still thinks are immoral, and I continue doing them because I’m being honest with both, the people I am doing them with and myself. Since the people who talk about morality are all usually such liars, that is not somewhere I like to go.

You also write about yoga rather persuasively. Do you feel that those who think of it as strictly physical exercise are missing out on some its other benefits? Does it help to think of it as spiritual?

Yes, I think it would. You know, I always say there is Bharatanatyam and there is a tarat-natyam. In Gujarati, the word tarat means turant, ‘instant’. There are Bharatanatyam teachers who will teach you the dance form for the right price in three months. Yoga is the same. There are people who have finished a 21-day course just yesterday and have become yoga teachers. This happens the world over. Learning from somebody like that, or learning online, and learning from a teacher who has really undergone that mind–body connect are two very different things. The difference, in fact, is quite huge.

Sarabhai in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 2009. Photo: Shailesh Raval/India Today

Sarabhai in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 2009. Photo: Shailesh Raval/India Today

As an activist, you have challenged governments and the highest institutions. How did you find the pluck and courage to throw stones at giants?

It doesn’t come like that. It comes because I can’t bear what is happening. And it comes because I have to tell myself that in this and in several other countries, I have a voice, and I must use it. If injustice goes against the very grain of my being, I must do something about it. But that said, I have never gone into it, saying I want to wave a flag. I have always gone into it when I have felt I can’t breathe anymore.

You have always been influenced by the ideals of non-violence. In the end, we wanted to ask, how much of a part has ahimsa played in shaping Mallika Sarabhai, the citizen and the person?

I think Gandhian philosophy on the one hand, and Tagore’s Where the mind is without fear … on the other, have both been in my DNA. I hate waste—whether it is a water tap left running or food being thrown away. I will reuse things whenever I can. I come from a very austere family on both sides, so austerity, Jain or Gandhian, is a part of me. Also, if I don’t want to be violated, I shouldn’t be violent. The trouble is that I have a razor-sharp tongue that sometimes gets its way before I can think and I have hurt a lot of people by that. I have, in most cases, gone and apologized, but people who know me well are often aware that 30 seconds after it has all come out, I will have absolutely nothing about that linger in my mind. But some people do get devastated by my tongue. This, too, makes me a work in progress.