When Civilizations Hunkered Down In Underground Cities To Survive Onslaughts

The authors unearth memories of a subterranean lockdown, from their past travels

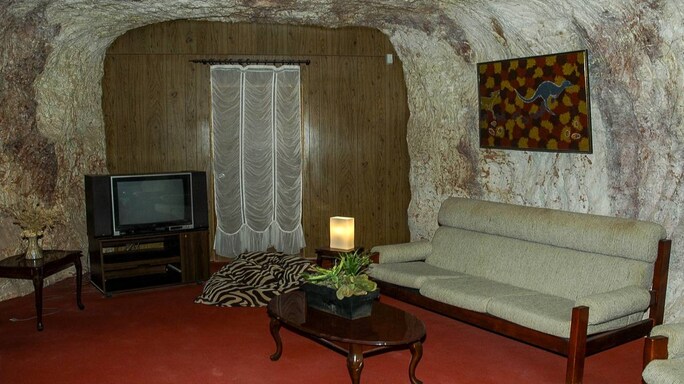

An underground home in Coober Pedy, Australia. (Photo: Gustasp Irani & Jeroo Irani)

An underground home in Coober Pedy, Australia. (Photo: Gustasp Irani & Jeroo Irani)

Would we emerge from the lockdown, hunch-back and pale, calcium and vitamin D deficient, resembling trolls from another world?

And today, as the world curls up and retreats into its shell to keep a rampaging virus at bay, we travel back in memory to the underground opal mining town of Coober Pedy in Australia, the cave dwellings in Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, the underground churches of Lalibela in Ethiopia and the underground cities of Cappadocia, where people in ancient times hunkered down in underground cities. And the message blowing in the wind was encouraging: We, too, will survive.

People carved out and lived in those subterranean dwellings for varied reasons: to protect themselves from a harsh climate, religious persecution and enemy attacks. At the time, we did not imagine that we too would, one day, burrow into our homes, shrinking away in fear from a virus for which the world had become a playground; the sun timorously filtering through open windows; a weak breeze stirring the curtains and admonished by the powers that be to stay home to stay safe, much like the ancient cave dwellers.

In Cappadocia in central Turkey, for instance, people lived for centuries in interconnected underground cities, each one with its own church, community centre, living quarters, barns, a network of tunnels. These were carved over millennia from volcanic ash rock, and on the surface, there was nothing to suggest these thriving metropolises ever existed: the ideal hideaway for communities seeking refuge from persecutors who came in different avatars – Romans, Arabs and other invaders and local warlords flexing their muscles.

A cave restaurant in Cappadocia, Turkey. (Photo: Gustasp Irani & Jeroo Irani)

A cave restaurant in Cappadocia, Turkey. (Photo: Gustasp Irani & Jeroo Irani)

We descended into the largest of the subterranean cities at Derinkuyu (7 BCE), ducking into narrow passages that connected the different precincts of the settlement, eight levels deep. We kept close to our guide at all times, for fear of getting hopelessly lost in an abandoned ghost city that once sheltered a population of 20,000.

At Lalibela in northern Ethiopia, we had to watch our step or risk falling onto the 13th century Church of St George that was five levels deep. That was because the monolithic church, carved from a single block of rock, was excavated into the bowels of the earth from top to bottom. In fact, the only hint of its existence at ground level was the Greek cross carved on the roof of the building. The high priest blessed us, while brandishing an ornate Ethiopian cross, and explained that the Church of St George, like its 10 interconnected siblings, was excavated into the protective arms of the earth to hide it from pillaging Arab invaders.

To hide from the rogues of the sea that encircled the Canary Islands, the aborigines of Gran Canaria (the third largest of the Canary Islands, off the north-western coast of Africa) dug deep into the mountains of the Guayadeque ravine. They thus lived peaceful lives, away from the gaze of marauding pirates. In 1478, the Spanish colonized the islands but the cave dwellers continued to burrow in their dugouts. Their latter-day descendants still do; they pray in an underground chapel, swill beer in a Tapas bar hewn into a cave and live in cosy cave homes adorned with family photographs. But no windows.

There were no windows in our underground hotel room in the opal mining town of Coober Pedy (established in 1915, current population 1,762) in the Outback in South Australia, either. Yet it was surprisingly cool even though there was no air-conditioning. This was something the miners realized a long time ago: even if the temperatures outside ranged from a searing 45 degrees Celsius during the day to near-freezing on winter nights, their mining shafts remained a pleasant 25 degrees Celsius. So, they worked their pickaxes to hew homes, underground churches, bars, restaurants, boutique jewellery stores near their mines! And as we look forward to the day when we will emerge from the ‘sunken city’ of our current lockdown and revel in the warmth of the sun and the caress of a soft wind, we recall the tenacity and courage of the residents who sought refuge in these subterranean wonders.