- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Bonus Read

- /

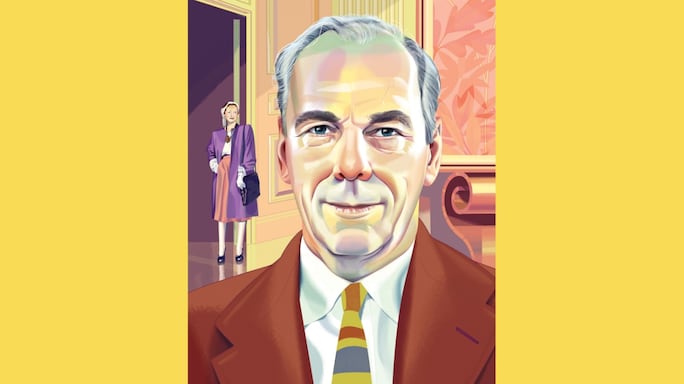

Unforgettable Dewitt Wallace

The remarkable story of the man who, with his wife, Lila, built Reader's Digest into a global success

He was a quiet man who said little publicly. DeWitt Wallace spoke instead through Reader’s Digest, which became the world’s largest international magazine. In its pages he told more stories and brought more information—and laughter—to more readers than perhaps any other man who lived.

The scene is Greenwich Village, New York City, one morning in January 1922. The Village, where rents are low, is a quaint bohemian place peopled by artists, poets and writers. Those who deal with the printed word come to New York to be near literary markets.

At No.1 Minetta Lane, in a basement storeroom office, the last copies of the first issue of Reader’s Digest, with a February 1922 cover date, are being readied for shipment. The work is supervised by DeWitt Wallace and Lila Acheson Wallace, founders and co-editors of the magazine. They have hired habitués of the speakeasy upstairs to help.

Finally, the last of 5,000 copies are wrapped, addressed, trussed in mailbags and set outside. A cab will take them to the nearest post office, from where they will be sent to subscribers. Then will come days of anxious waiting to see if the little newcomer is indeed what the world has been waiting for.

Lila Acheson Wallace, 32, is brunette, blue-eyed and petite. A social worker, she had been an English teacher before the war. She has been Mrs DeWitt Wallace for three months.

DeWitt Wallace—Wally, as he came to be called—also 32, is tall and lean, and moves with easy athletic grace; in his teens, he’d played semi-pro baseball. In the eyes of his family he is something of a flop. His father, James, is a Greek scholar and college president. DeWitt is a college dropout who has gone from one job to another. Fired most recently by a firm in Pittsburgh, he has come to New York to publish a homemade magazine.

It measures 5½ by 7½ inches. Consisting of 64 pages including the covers, the magazine is half the thickness of your little finger. This ‘pocket size’ will be its first bid for attention, the dimensions signifying that all within is compressed and condensed. As for content, it’s just informative, helpful articles—no fiction, no pictures, no colour, no ads.

Will the little magazine appeal to readers? For two years, professionals in the business have been saying no. So now with the help of his new bride and a couple thousand dollars, much of it borrowed, the amateur is going to try to wing it on his own.

Lessons From Life

His brothers and sisters knew DeWitt, the third son of James and Janet Wallace, as dependably unpredictable. He was a prankster at school, attending Macalester College in their home city of Saint Paul, Minnesota, where his father was a professor. Although the virtues of academic excellence were regularly extolled to all the Wallace kids by their parents, the family finances were dismal. Wally determined he would one day make a fortune.

He spent the summer of 1911, when he was 21, selling maps door-to-door in rural Oregon. His first day out, he sold only 12. So he talked with veteran salesmen in hotel lobbies, picking up their strategies.

DeWitt and Lila did much of the work under a New York speakeasy (shown right).; Photos: Reader’s Digest archives

DeWitt and Lila did much of the work under a New York speakeasy (shown right).; Photos: Reader’s Digest archives

Selling fascinated him. At night, he read magazines, writing down notes to retain useful ideas about getting ahead in business. As he widened his circle of acquaintances, he discovered he could learn from anybody he could talk to.

And this was an age that saw information emerge, when change itself became the big news of the 20th century. Wire services and newspapers flooded readers with every latest detail and speculation. Their emphasis was on speed. Yet many harried readers found themselves so carried along by a tide of information that they could not distinguish between what was meaningless and what facts fit into a larger pattern. DeWitt found newspaper treatments tentative, hasty. A magazine—halfway between newspaper and book—offered time to discern the significant, to develop an underlying theme, while still dealing with the fresh and new.

It was also a pivotal period in the history of man’s aspirations. Self-improvement was the key, and success could be achieved through learning. But truth was transient: with new discoveries it had to be grasped and re-grasped.

DeWitt, alive to what was fresh and new in a rapidly changing world, devoured magazines. He jotted down anything that might be of use to him, a practice he had started at age 19. To his father, James, he explained: “I have 3x5-inch slips of paper, and when I read an article I place all the facts I wish to preserve or remember on one of these slips. Before going to sleep at night I mentally review what I’ve read during the day, and from time to time I go through the file recalling articles from memory. I do not see why time thus spent is not as beneficial as if spent studying books.” Sometimes a quote or simple outline didn’t suffice. Wally would then copy down in tiny but legible script the essence of the article as a whole, condensing it in the writer’s own words.

To DeWitt, the world of business was emerging not simply as a way of earning a living but as a different kind of educational system. For the youngest son of a high-principled academic family to go into the money-making business would raise questions from some about moral values because, to many, progress meant materialism. Yet for the great majority, including DeWitt, man’s material progress promised a new age, a time of fulfillment when everybody would have enough of everything.

In 1951, Time magazine featured an eight-page story on the remarkable success of DeWitt and Lila Wallace.

In 1951, Time magazine featured an eight-page story on the remarkable success of DeWitt and Lila Wallace.

This belief—the American dream—got support from the life story of American industrialist Andrew Carnegie. One of the world’s richest men, he published his philosophy of philanthropy, which declared that a successful businessman was morally obliged to continue to accumulate wealth in order to give it away. Carnegie also knew the value of reading and how it democratized privilege. He gave $60 million to build some 2,500 libraries throughout the United States and the English-speaking world, some of which DeWitt spent time in devouring books on subjects he didn’t know a lot about. (Once while delivering maps, Wally stopped to watch a courtroom trial. The contest of wits between attorneys fascinated him. So one rainy night he walked to one of Carnegie’s libraries and came away with The Art of Cross-Examination by Francis Wellman. He read the book in its entirety, then wrote his father fervently about the experience.) For a self-directed learner like Wallace, a system designed to supply any seeker with useful information on almost any subject was ideal, and he made full use of libraries.

DeWitt attended university but in spring 1912 dropped out for good. He took a desk job at Webb Publishing Co. in Saint Paul, handling inquiries about Webb’s agricultural textbooks. At night, he continued collecting kernels of practical wisdom from his magazine reading. Could his notes provide the basis for some kind of publication offering distilled business counsel and pointers for achieving success?

After leaving his job, he got to work and in several months produced a 128-page booklet, Getting the Most Out of Farming. It listed and described the most useful bulletins put out by the government about agriculture. He then set out in a second-hand Ford on a five-state selling trip, aiming especially at banks and seed stores that might buy the booklet in volume to give away to farmers. In several months he sold 1,00,000 copies and paid off his expenses. He netted nothing, yet he had learnt how to put out a publication.

He was considering how to follow up when the idea hit him: He could do a periodical aimed not just at farmers but at all readers interested in informing and improving themselves, and in getting ahead in the world.

Needing to make a living until he could launch such a magazine, Wallace took a job with a manufacturer of calendars; this was in late 1916, a few months before the United States entered the war. But the big idea was there in his mind. Maybe his recording of the essence of articles he’d read could serve as the basis for something. Among his notes was this one: “Never fear, there is a strong undercurrent of desire for knowledge. Supply it and every dollar’s worth of printed matter will come home to roost.” The observation would be validated in the coming years.

“A Gorgeous Idea”

The notes were interrupted by the Great War. On the fifth day of the Meuse-Argonne offensive in October 1918, shrapnel fragments struck Sergeant Wallace of the 35th Infantry Division in the nose, neck, lung and abdomen. One piece of metal came within a hair’s breadth of slicing open his jugular vein. “In which case,” a medic amiably explained, “the only way we could have stopped the bleeding would be by choking you to death.”

Instead, the lucky young man was blessed with a few months of convalescence at a US Army hospital. Ambulatory and at leisure in a place supplied with magazines, he now concentrated on his idea: a general-interest digest. He’d read, then select articles and boil them down as he copied them in his chisel-clear handwriting.

Once back home in Saint Paul, over six months in the public library he built a stockpile of choice articles. Finally he put together 31—one for each day of the month, each cut to two pages or less—and had a printer run off several hundred copies of this sample Reader’s Digest. It was dated January 1920. To finance the project he had tapped his older brother Benjamin for $300. His father at first refused a like amount, pointing out that DeWitt was hopeless at managing money. But James Wallace was finally persuaded to help by the argument that readers were “anxious to get at the nub of things.”

Proudly, Wally started showing his dummy around Saint Paul and then to the big publishing houses, willing to give his invention away to anyone who’d publish it and sign him on as editor. One after another, publishers turned down the idea as naive, or too serious and educational.

Dejected, the ex-sergeant found his fortunes at low ebb. There was a single compensating bright spot. One day, he ran into Barclay Acheson, a college friend. DeWitt had once spent the Christmas holidays at the Acheson home, where he was much taken with Barclay’s sister, Lila Bell—“a dream of a girl.” Nothing came of it at the time: She was already engaged.

During the war she had made a career of helping to improve conditions for female factory workers, and now she was still at it, working for the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) in New York. Wallace, on hearing from Barclay that she had not in fact married, fired off a telegram to her: “CONDITIONS AMONG WOMEN WORKERS IN ST. PAUL GHASTLY. URGE IMMEDIATE INVESTIGATION.”

By chance Lila was already scheduled for a temporary assignment in Saint Paul. On her first evening there, Wally proposed; on the second, she accepted. Only after they were engaged did he give her a copy of his sample magazine. “I knew right away it was a gorgeous idea,” she said later.

Though practical considerations prevailed—she returned to New York, and he took a job writing promotional copy for Westinghouse Electric in another city—he never stopped thinking about his own magazine.

In 1921, Wally was laid off. That did it. In his gloom, he saw anew the brilliance of a suggestion that had been given him by a fellow worker—why not sell the magazine directly to readers, by mail? Immediately, on his portable typewriter in his rented room, he began pounding out letters soliciting subscriptions. He hunted for lists of people—nurses, preachers, members of clubs. From college catalogues, he got names of faculty members.

The pitch had to be particularly good since what he was peddling existed only in his mind. But he offered a provisional commitment—the subscription could be cancelled and all money refunded if the reader wasn’t satisfied. For four months, he wrote and mailed out letters, each with an individually typed first page. Then, in October 1921, he left for New York, and Lila.Together they did two things: They got married at a church in the small town of Pleasantville, 48 km north of the city, and they formed The Reader’s Digest Association. Settling into a Greenwich Village apartment, the couple got out another batch of letters before going off on a two-week honeymoon north of the city. Replies from these letters brought the number of paid subscribers to 1,500, each subscription accompanied by $3; they had enough cash to put out a first issue, maybe even a second.

That first issue of Reader’s Digest featured, in its lead article, the great inventor Alexander Graham Bell and his belief that self-education is a lifelong affair: “The very first essential of any real education is to observe. Observe! Remember! Compare! It is the foundation of all education.” The article was an accurate reflection of the mind of DeWitt Wallace, college dropout, self-educated man and founder of Reader’s Digest.

To help pay the printer, Lila had sublet one room of their small apartment, sharing their kitchen and bath with another couple. Now they waited. What if even one-third of the subscribers wanted their money back?

Letters From the Editor

There were no cancellations. So the editors got busy on a second issue. Lila kept her social-work job to pay the rent. Wally went uptown each day to forage through magazines in the New York Public Library and thus avoid having to buy them. He condensed articles that engaged his mind, writing in longhand on yellow sheets of paper, eliminating asides, pruning wordy prose, getting straight to the point.

In September 1922, the Wallaces rented a garage apartment for $25 a month in Pleasantville, the town where they’d been married. Orders kept coming in as Wally kept mailing out promotions. By the end of the magazine’s first year, circulation had increased to 7,000. More working space was needed, so for $10 extra per month the Wallaces rented a pony shed beside the garage. They brought in typewriters and stencil-cutting machines, and hired neighbourhood help.

Wally still wrote his own promotion circulars and letters that were personal in tone. Some envelopes were handwritten. His direct-mail approach established a personal connection, a kind of companionship between editor and reader. The promotion letter you got was from the man who originated and produced the magazine, asking you to subscribe for your own good. Other magazines launching at about the same time aimed at millions of readers. The upstart Reader’s Digest aimed at the individual—and out-succeeded the whole pack.

When they began to feel prosperous enough, co-editors DeWitt and Lila would go somewhere to escape interruption and, in a seven-to-10-day work binge, put together the next issue. They’d take adjoining hotel rooms, he working in one and giving her a batch of publications to read in the other. To rule out distractions they communicated by notes slipped under the door. He kept all her notes.

This one was scribbled on a pad of the St. Regis Hotel in New York: “I’ve covered 12 issues of each of these magazines, darlin’—and I am a tired baby! Hope there is something useful. Come and kiss me good nite.”

Once during those early years after he’d left on a trip, she wrote: “Make the most of this trip, Sweet, for I am not at all sure I’ll ever be able to let you go away without me again! You looked so sweet and desirable as you drove off that I almost lost my courage and didn’t keep my promise not to weep a bit.”

Wallace had originally set himself a goal of 5,000 paid readers. That would bring in $15,000 a year—enough, in 1922, to cover costs and provide a comfortable living. They might even be able to travel, taking the issue with them to work on at will. After four years, however, Reader’s Digest circulation had reached 20,000. Then in the next three years it skyrocketed to 2,16,000. As the magazine kept growing, the Wallaces began renting whole floors in various Pleasantville office buildings.

For decades, RD’s world headquarters were located near Pleasantville, New York.; Photo: Reader’s Digest archives

For decades, RD’s world headquarters were located near Pleasantville, New York.; Photo: Reader’s Digest archives

One day Ralph E. Henderson, 26, turned up at the pony-shed office looking for an editorial job. Ralph records the DeWitt Wallace who hired him: “He listens far more than he talks. But his quick eyes are the clue to his restlessness, energy, curiosity. All editorial work went on in the living room, where Wally had his desk. There he would read 40 or 50 magazines regularly, select 30-odd articles and condense them with painstaking care. That’s the way it went, straight from the pencil-marked magazine article to the typed yellow sheets for the printer. Every scrap of copy had to flow through his own portable Corona typewriter. In the same room Lila had her piano, which she played often. So the click of the Corona and the notes of ‘Blue Room’ sometimes reached the nearby studio office where I worked, in a mingled sonata.”

It is a storybook view: a young couple, not needing to hold hands to be in love, on their way to a stunning success. When I joined RD in 1930, we were a dozen people in cramped quarters on the top floor of a bank building. Below were train tracks: Every hour or so the peaceful atmosphere was disturbed by steam engines roaring past. My job was to help the boss in dealing with writers, drumming up more original articles.

While driving around one Saturday afternoon in 1935, Wally went off the road and damaged his car. The tow-truck operator gave him an earful about other smashups he’d seen, and the bodies dragged out of those wrecks. Mulling this over, the editor decided that if he could make readers see, in grisly detail, the carnage on our highways, it would shock them into better driving habits.

He dispatched a young writer named J.C. Furnas to talk with police and highway patrolmen, getting graphic eyewitness reports of ‘worst case’ accident scenes. The article that ran in the August 1935 issue was a blockbuster. For all its guts and gore, it had dignity. Five thousand proofs of —And Sudden Death were sent out to newspapers and other publications, with permission to reprint, in order to reach as many drivers as possible before the upcoming long weekend. It ran in newspapers in every large US city and in many other publications. It was read and discussed on radio, in schools, churches, lunch clubs. The demand for reprints of the article would continue for two decades. It was without doubt the most widely read article ever published at that time.

Fortune Smiles

Most people in the publishing world had regarded Wallace as a scissors-and-paste editor, putting out a little reprint magazine. Yet this quiet, obscure fellow had now originated a piece that rocked the nation. Along with envy it raised a suspicion of editorial genius. In succeeding years, original articles became a major component of Reader’s Digest. Stories about the perils of fascism and communism, the hazards of cigarettes and drugs, exposés of drunken driving and government waste became hallmarks of the magazine’s investigative journalism.

By 1936, RD’s circulation was 1.8 million—the largest ever achieved by a 25-cent magazine (save for Good Housekeeping). With no ad revenue, the ‘pocket university’ had nonetheless netted its husband-and-wife owners $4,18,000 the year before. The man was not only a creative editor, he was apparently a financial wizard too.

Though DeWitt listed Lila’s name ahead of his as editor, she had little interest in editorial work. Yet Lila’s competence in the world of artwork and decor equalled his in the realm of words and ideas. She took on the responsibility of having a new home built on an estate big enough for a landing field. (Wally loved piloting a four-seat plane—which he eventually gave to Canada in support of Britain’s war effort.) And when the operation of Reader’s Digest from four rented locations was no longer viable, Lila oversaw construction of new offices on an 80-acre site in the countryside near Pleasantville, starting in 1937. She also took complete charge of the landscaping and interior decoration. Furnishings would include original antiques and works of art.International editions and other RD products, including books, followed. In 1955, the magazine opened its pages to advertising (but only after polling readers, who agreed with the change). Profits mounted. By 1980, the combined wealth of the Wallaces was reckoned to be half a billion dollars.

Having had no children, the couple had no interest in a dynasty but instead became legendary givers. They gave millions to schools and established a travel-research fund for journalism students. Some $2 million was donated to restore the periodicals room in the New York Public Library, where DeWitt had once copied articles by hand. The library named the room after him.When, in 1941, the company received $71,040 in profit after publishing an anthology, Wally divided the money among 348 employees. Their gratitude gave him a heartening awareness of his influence, and he continued the habit for as long as he lived. In 1976, for example, he rose at a company party and said: “Lila and I hate to act impulsively and unilaterally without waiting for the next board of directors meeting. But …” He then gave a surprise raise to all 3,300 employees: 11 per cent for those making up to $40,000 a year, and eight per cent for those making more.

Wally published several pieces about Outward Bound, an adventure-based education course that puts young people through a programme of outdoor activities to gain self-confidence. Once at a meeting in New York, DeWitt slipped an envelope into the pocket of Joshua Miner, president of Outward Bound, USA. “Inside was a letter and a cheque for one million dollars,” Miner reports.

Lila became best known as a patron of the arts. From a fund she established, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art received well over $50 million. She made arrangements for fresh flowers to be kept in the museum’s great hall, in perpetuity—one instance of her wish to match nature’s beauty with art. Another was the restoration of painter Claude Monet’s studio and gardens in Giverny, France.

Horizons of Hope

For all his wealth, achievement, and power, DeWitt Wallace saw himself as an average man. But he stood out for his intense, sustained curiosity, plus an unequalled capacity for work. He had mountains of material to deal with. Reading with single-minded absorption, quick with decisions, he managed to clear his desk and always be on schedule.

Wherever he travelled, he brought home postcards to use at Christmas. He would hand-address each one and write a cordial personal message. The cards went to writers, agents, publishers and some staff—complimenting each on a particular achievement in the past year that had helped make Reader’s Digest a success. It was a practice he followed for decades. He timed himself with a stopwatch and set an hourly standard to compete against. One holiday season he sent out 800 cards!

Wally continued to believe the road to human betterment stretched into the future. This conviction made many editorial decisions for him, enabling him to respond with spontaneity and honesty. Information set forth in cogent style that advanced people’s hopes and widened horizons—this is what stirred him. ‘Quotable’, ‘memorable’, ‘applicable’ were words he lived by. In starting up his little magazine he had made no calculations or surveys of what the public wanted to read. He knew only what he wanted to read. It was understood that the views expressed in RD, large or small, pretty much represented Wallace’s.

In 1973, at the age of 83, Wally and Lila officially retired. Yet Wallace remained fully in touch, though was seen less often at headquarters. When, in 1976, a newspaper referred to ‘the late DeWitt Wallace’, he sent his staff a memo: “Here Lila and I are in the Glorious ‘Out Yonder,’ looking over your shoulder and applauding the work you are doing as we did in our previous incarnation.”

The Wallaces in front of Marc Chagall’s The Three Candles, which was part of their extensive art collection.; Photo: Reader’s Digest archives

The Wallaces in front of Marc Chagall’s The Three Candles, which was part of their extensive art collection.; Photo: Reader’s Digest archives

In 1978, the Christmas card was not hand-signed. DeWitt had typed: “My close-up vision has deteriorated in recent months. I have difficulty reading my own handwriting. Hence I refrain from inflicting upon you a personal note, something I enjoyed doing in the past.” The editor who believed all problems are solvable had finally encountered some he could do nothing about.There were times still when the young man reappeared in the old. When he was 88, he got Josh Miner of Outward Bound to help him set up a white-water expedition on the Green and Colorado rivers. He commandeered a party of men in their 70s to run the rapids with him.

Such spurts of energy, however, were increasingly rare, and on 30 March 1981, DeWitt died at age 91. Lila lived another three years.

During Wally’s last years I felt a kind of homesickness for the past when everything still lay ahead. I kept remembering all those afternoons when he and I would leave the office above the train tracks and drive out to the country where the new office building was going up. With each visit his original indifference turned into an almost juvenile pride in the construction.Soon after his death I came across a fragment of verse from Japan, a haiku translated. It spoke to me as music does and it said what I could not:

“A trill descending …But look! The skylark who singsThat song has vanished.”*

Grief is a poor afterthought, and frailty does not mark the end. Millions of people around the world continue to imbibe inspiration from the magazine DeWitt Wallace created. The skylark has vanished, but not the song.

* From Haiku Harvest, translation by Peter Bielenson and Harry Behn, ©1962 by Peter Pauper Press.

This article was originally published in February 1987.