- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Classic Reads

- /

Triumph of an Olympian

Competitors from different countries, the two men showed the world the true meaning of sportsmanship

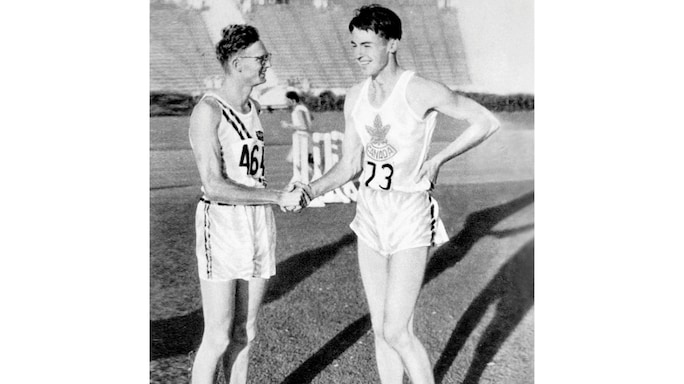

Bob Van Osdel (left) and Duncan McNaughton greet one another at the Olypmic field. Photo: ©PA Images/Alamy Stock

Bob Van Osdel (left) and Duncan McNaughton greet one another at the Olypmic field. Photo: ©PA Images/Alamy Stock

Sorting through the mail one morning in the spring of 1987 in his comfortable home outside Austin, Texas, Duncan McNaughton spotted a letter from the wife of his old friend Bob Van Osdel. Pulling the note from the envelope, he began to read, and sadness crept over him. Bob, his friend for half a century, was dead at the age of 77. With the note was an obituary from the Los Angeles Times. As Duncan, then 76, read the headline—Trojan Olympian Offered Costly Advice—his grief turned to anger.

They’ve got it all wrong, he thought. As he sat down to write a note of condolence to Bob’s wife, his mind went back to the day when two young men took each other on in a heart-stopping high-jump competition and cemented a friendship that lasted a lifetime.

It was 31 July, a balmy afternoon in Los Angeles and the first full day of competition at the 1932 Summer Olympic Games. Arriving at the high-jump pit with 18 other keyed-up jumpers from 11 different countries, Duncan and Bob exchanged a quick, amiable greeting and went their separate ways to limber up.

For more than two years, the two men had been members of coach Dean Cromwell’s fabled University of Southern California (USC) Trojan track team. School work commanded most of their time, but the two practised together two or three times a week and often spent weekends together at various meets. Almost inevitably, they had become friends.

Bob sails over the ever-higher jump bar. Photo: ©ap/shutterstock

Bob sails over the ever-higher jump bar. Photo: ©ap/shutterstock

Though united by their sport, the two were quite different. Bob was a studious, bespectacled dental-school student from Long Beach in southern California, with a masterful grasp of the techniques of high jumping. Duncan was a dashing carefree science student from Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada, a born athlete who took to high jumping as he did to most sports—easily and naturally.

In high school Duncan had preferred basketball to track-and-field. He’d taken up the latter in the off-season and taught himself the ‘western roll’ high-jumping technique from an athletic how-to book. He was soon a star, winning championships in jumps, sprints and hurdles. But he might have dropped track for basketball had he not won a scholarship to the University of Southern California, where he fell under Bob’s wing and made the Trojan high-jump team.

Bob had helped the younger man perfect the revolutionary mechanics of the western roll. The jumper plants the foot closest to the bar as he reaches his take-off point, then kicks up hard with the other to elevate his hips. The kick, that upwards thrust of the outside leg and foot that lifts the body, is at the heart of a successful jump. As he clears the bar, the jumper, his side parallel to the bar, begins to roll, so that he is facing down as he lands in the pit.

With the 1932 Olympics approaching, Canadian officials soon realized that the 21-year-old Duncan could be added to their team at little cost, a major consideration as the Depression began to bite. Although he had been improving steadily, Duncan was still losing to Bob three times out of four in lower-level competitions, and the lanky Canadian had no illusions about his ranking in the high-jump universe. The heights he’d been jumping suggested he was sixth or seventh in the world that year, not only well back of his friend but also others on the American team.

With luck he figured he might make the top four in the Olympics. But only just. The Olympic high-jump record, set in 1924, was 1.98 metres. Duncan had never jumped higher than 1.94 metres; Bob, on the other hand, had jumped more than 2 metres.

Suddenly 31 July—opening day—was upon them. Neither man had ever competed before a crowd as large as the 1,00,000 or so rapidly filling the seats of the newly expanded Los Angeles Coliseum, and both were doing everything they could to keep their nerves in check.

Duncan fixed his attention on the area in front of the high-jump stand, noting the soft, somewhat spongy condition of the turf as he marked off the distance to the bar. Don’t slip, he thought, as he drew a mental sketch of the approach he’d make, the kick that would send him skywards and the soaring roll that would see him clear the bar.

As officials set up the black-and-white striped bar for the opening jump of the afternoon, Duncan stripped off his warm-up jersey, glanced down at his singlet with the Canadian red maple leaf above the number 73, and painted another mental picture of his first jump, now only moments away.

Opposite him, on the left side of the jump, Bob stretched, adjusted his glasses and did the same. Of the two, the 22-year-old was the clear favourite.

The bar was set around 1.8 metres just after 2:30 in the afternoon when an official gave Duncan the signal to make his first attempt. He fixed his eye on the bar 15 metres ahead.

Everything went just as he’d visualized it. Hitting his take-off point, he planted his right foot, kicked up with his left and sailed over. Landing in the sawdust on the other side, he felt himself relax. As the afternoon wore on, the official black-and-white striped bar inched inexorably upwards, and the 20-man field began to narrow.

Dunc, as everybody called McNaughton, preferred big meets and usually performed better as the stakes increased. But his nerves were being rattled by the jumper just ahead of him, who would take out a tape before each try and remeasure the length of his run to the jump.

But now even this minor irritation was gone; that jumper had just sent the long bar flying and was out. So was another potential threat, American George Spitz, who was the favourite after clearing 2 metres on five occasions earlier in the year. But Spitz slipped in the soft take-off area at the base of the Olympic jump and went out at 1.85 metres. His friend, Bob, however, was having a good day, soaring over the bar time and again with the style and assurance of a champion.

By late afternoon, Duncan’s hopes of making the top four had been realized. The field was down to a Los Angeles high-school student named Cornelius Johnson, Simeon Toribio of the Philippines, Bob and Duncan.

Duncan clears the bar during that long summer's afternoon.Photo courtesy of bc sports hall of fame archive

Duncan clears the bar during that long summer's afternoon.Photo courtesy of bc sports hall of fame archive

The bar was raised to 2.007 metres. All four failed. An expectant buzz spread through the stands and wafted out over the field in the still summer air. When the bar was lowered, Duncan and Bob made it over. Toribio and Johnson did not. The two friends would go head-to-head for the gold.

With all eyes on the high jump, officials quickly called a halt to competitions elsewhere in the massive stadium. An attentive crowd tensed for the showdown.

Bob had proved himself the better jumper. But as that long afternoon wore on, as the two hurled themselves over the bar again and again, Duncan found himself with an unexpected advantage over his friend.

As a teenager he’d packed gear for his father, a civil engineer. Hauling all that powder, lumber and equipment over mountain ridges and down into valleys had been ideal training for an aspiring high jumper, adding to his stamina and strengthening his legs. It was nearly six o’clock, and the two had been jumping for more than three hours—Duncan from the right side, Bob from the left. Both were succeeding on some tries and missing others, but never in a sequence that would make one or the other the winner.

Relaxed and loose, oblivious to the intermittent roars of the huge crowd, the two were feeling less and less like rivals in a high-stakes Olympic match and more like buddies at a daily practice session. As time went on, however, both jumpers seemed to be tiring from the prolonged competition. Bob, long accustomed to watching his amiable acolyte with a critical eye, had winced when the Canadian had hit the bar and knocked it off on his last jump. As Duncan readied himself for another try, Bob walked over to him.

“Dunc,” he said, “you’ve got to get that kick working. If you do, you’ll be over.” Bob would lose if Duncan succeeded, but he never gave it a thought.

Duncan hadn’t been conscious of the problem with his kick. Now that he was, he focused on it. He crouched, fixing his eye on the bar. Then, springing forwards, he hurtled ahead to his take-off point. He planted his right foot and kicked like he’d never kicked before. He exploded upwards into the air, his arms outstretched like wings, and in one suspended, unforgettable moment, he was free of the earth and over the bar.

Bob then took his jump, taking the bar with him into the pit. Duncan had won the gold medal with a first jump clearance of 1.97 metres.

It came to him not as a flash of euphoria or flush of triumph but as utter surprise. What happened here? he asked himself as the stadium erupted in cheers. At his side was his tired friend and temporary rival, Bob, smiling a generous “well done”.Then an exuberant Australian shouted congratulations for “beating the hell out of those Yanks,” and Duncan came back to earth, appalled. Those were his teammates the Aussie was putting down. And more to the point, it was Bob’s last-minute advice that had helped him win. It was a selfless gesture, and with it, Bob had expressed the highest ideals of Olympic competition.

The competition over, the men share a moment together.Photo courtesy of bc sports hall of fame archive

The competition over, the men share a moment together.Photo courtesy of bc sports hall of fame archive

From that day on, Bob and Duncan’s friendship would never falter. Bob graduated in dentistry from USC in 1934, and Duncan earned a master’s degree in science from the California Institute of Techology in 1934. Then World War II caught up with both men. Duncan enlisted with the Royal Canadian Air Force and flew 57 trips as a Lancaster bomber pilot, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross. After the war he completed a PhD at USC and became a successful consultant in the oil and gas exploration business. Through it all, the bond with Bob remained strong.

Bob served in the US Army Dental Corps, and when he returned, he settled in Los Angeles where he became Duncan’s dentist and the godfather of his oldest daughter. And when Duncan’s gold medal was stolen from his car during a move, Bob had a new one made for him using a mould cast from his own second-place silver.

After learning of Bob’s death, Duncan remembered his friend’s sportsmanship as a great moment in Olympic history. “I may have won the gold that day,” he said, “but Bob Van Osdel showed what champions are made of.”

More important than medals, than winning, was the gesture of a friend.

Duncan McNaughton died on 15 January 1998, at age 87. This article originally appeared in the August 1996 issue of Reader’s Digest.