- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Personalities

- /

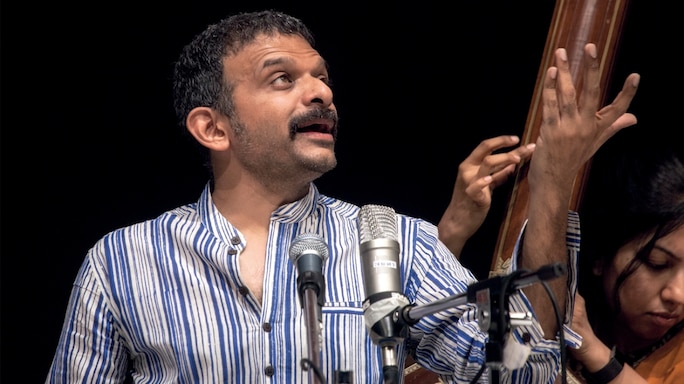

The Voice of Change

For T. M. Krishna, the world is a stage, and he has chosen to play the subversive’s part

Credit: Hariharan

Credit: Hariharan

Like any other classical form, Carnatic music is first a language. T. M. Krishna began to learn it when he was five. By the time he was 12, he was performing for live audiences, and by his late twenties, Krishna was already being hailed as one of the greats. Having mastered the conventions of Carnatic music so thoroughly, he could fill almost any concert hall. For this celebrated vocalist, however, neither mastery nor renown was enough.

Success didn’t satisfy him—it made him introspect instead. Today, at 45, Krishna is arguably Carnatic music’s most familiar exponent, but his reputation isn’t that of a conformist—he is a rebel with the courage to defy tradition through performances that reinterpret both Carnatic form and content. Krishna’s battles, though, are fought on two fronts: aesthetics and ethics.As he questioned implicit class and caste hierarchies that define both the art he practises and the world in which he lives, Krishna didn’t just talk about his conclusions, he also wrote them down. In 2013, when he released his book, A Southern Music, the world of Carnatic music was up in arms. He had accused it of discrimination, and no matter the extent of the backlash, he would not back down.

Over time, Krishna’s critiques have become even sharper. His tweets attack orthodoxy and bigotry in all its forms, political and cultural. His music, meanwhile, makes us revise notions of the sacred and sublime. In 2016, he received the Ramon Magsaysay Award for using art to “heal India’s deep social divisions”. Speaking to Reader’s Digest, he opened up about his politics, pluralism and his preferences.

You were in college when you decided to become a professional musician. What were your initial impressions of the world of Carnatic music? Did you find it stifling?

I grew up in an environment rooted in a kind of intersection of upper caste and cosmopolitan upper class. The world of music I entered was quite similar. It was a confluence of all kinds of privileges, and that’s the only world I knew. I’d be lying through my teeth if I said I found it stifling—I loved it. I loved everything that came with the privilege of the ‘aesthetic’ caste, if you can call it that.

In those early days, you were called a traditionalist, a purist. How did you respond to those labels?

I loved being called a traditionalist. People like me reminded older listeners and connoisseurs of musicians from the early 20th century. So, if your style is compared to performers of the ’40s and ’50s—people you worship—you love it. Oxymoronic as it sounds, I saw myself as a generation stalwart. It was not enough that I got a full house. It was also important that I was seen as a hard-core, serious musician, who could do all the difficult things and touch your heart at the same time.

But if I’m not mistaken, weren’t you also doing unorthodox things around that time—singing a varnam as the main piece, instead of the usual kriti?

That happened later, around 2004. I started reimagining the concert experience. That’s when people started saying I’m not a traditionalist. That tag suddenly disappeared. Now I was there to destroy tradition, to do whatever I wanted, because I had the tenacity and the privilege to do so.

One gets the sense that there came a point when something transformed in you. Can you describe for us that process of change?

I have always loved singing, and after a while, I had figured out how to perform successfully. I could go to a concert and make everyone cry, laugh and applaud as I wanted. I say this with some arrogance, but I say it because it was only when I was hailed as the star of the next generation that a few questions began to appear. The triggers were moments in my concerts when I had no control over the music. The music overwhelmed me. When I saw my will disappear, I was confused. How is this possible? I asked. It was not ‘mastery’ that had got me here. I realized what was happening was purely musical, nothing political or social.

T. M. Krishna sings at Chennai’s Urur Olcott Kuppam Vizha in 2018. The art festival was started by him and environmentalist Nityanand Jayaraman in 2014; Photo Credit: Smitha Suraj

T. M. Krishna sings at Chennai’s Urur Olcott Kuppam Vizha in 2018. The art festival was started by him and environmentalist Nityanand Jayaraman in 2014; Photo Credit: Smitha Suraj

It sounds almost like a dissolution of the ego …

It was, you’re right. It is something we all go through in patches. I remember the first question that appeared in my head—where did the music come from? Philosophically, one could say music is not in the command, but in the surrender. But there were other questions, too. Is the joy derived from music created simply by the times and the cultural context a set of people find themselves in? Importantly, what is beauty? Are we truly sharing beauty, or are just sharing a habit? Now the moment you get into such a space, you start seeing layers you would otherwise never consider.

As a performer, I asked myself an even simpler question: If I completely break down the performative form, will the music still exist, or is the music trapped in it? I was hoping to find music that existed far, far beyond what necessarily generates the applause, so I soon started going to concerts with a blank slate. I remember, in 2011 or 2012, I was performing during the famed December Music Season in Chennai. I sang one piece for 40 minutes, and, musically, there was nothing else for me to offer after that. I announced that I could sing for another one-and-a-half hours, but that would be mechanical. So, without realizing the consequence of what I was doing, I left. I was called irresponsible. Someone said I was high on drugs. Another said I was having family problems. I did not explain why at that moment I felt ‘complete’. Maybe I did not want to. The truth is, after that incident, I have never stepped off the stage, even though I have wanted to so many times.

In 2015, you announced that you would no longer perform at the Chennai music season. I’ve heard of no Carnatic musician ever doing this. Why exactly did you feel the need to take this step?

I have been part of this music season since I was five or six. It was as a listener walking down the corridors of all these sabhas in December that I learnt all the music I did. It’s very close to my heart. I can, of course, politicize it, but I can’t deny the experience, the buzz. While I find that conflict quite exciting, I also could not find a space that would help me reconcile these two feelings. That’s when I stepped out. Sure, it’s during the December season that you’re recognized by a larger group of rasikas, music lovers, who come from all over the world and all over the country, but the season is also a celebration of a Brahmanical mindset that marks an inside and an outside. This was really oppressive for me. There are other issues, too. Nepotism is one, but there is also no outreach. The larger community of the city is not involved, not even invited to be part of this cultural celebration. There are no free passes for students of music from marginalized communities, for instance. All this would really bother me, so, finally, I thought I need to step aside and find my own groove.

You have performed Rabindra Sangeet and sung ‘Allah Tero Naam’ during Carnatic recitals. How are audiences responding to this and how has the world of Carnatic music reacted?

Honestly, it ultimately depends on where the concert is happening and who is listening. When I started incorporating different sounds—semantic and melodic—in my repertoire, there was discomfort in the inner world of Carnatic music. Also, this discomfort wasn’t only aesthetic. I was making a political statement and that made it harder to digest. That’s something that still continues to bother people, but over the last three or four years, I see small shifts in how younger people are trying to do things. The coming generation is also thinking about things like concert format, etc. They will chart their own path, but there is movement there. If I had met today’s T. M. Krishna 15 or 20 years, I too would have criticized what he was doing and said he was destroying Carnatic music. I know the arguments that people make. I used to make those same arguments once.

Historically, young people have found classical music inaccessible, but your concerts seem to attract the youth in droves. What draws them more, you or your music?

[Laughs] I think it has happened both ways. There are a lot of young people who say they want nothing to do with classical music. This is because the classical world portrays itself as being beyond reality, as floating in mid-air. People make the mistake of thinking the young don’t like classical music because it’s too complicated, or because its sounds are not modern. This is all bunkum. It’s the culture around it that puts people off. When you are told that you are uncultured if you do not understand this music, you will, of course, not want anything to do with it after a point. I think young people started coming to my concerts because while I was singing that same music, I was also admitting that we are a deeply problematic lot. I was questioning the culture. There was also a sonic shift in my music. I slowed Carnatic music down. People were fascinated by the possibility that music can have different voices.

In A Southern Music, you write about how gender, class and caste have come to impact the performance and practice of Carnatic music. Did you have to face any backlash for this?

Oh, there was huge backlash. Everybody knew a book was coming, but they just expected it be some kind of analysis of Carnatic music and its history. Nobody was expecting a set of essays that would bring together the political, the social and the aesthetic. Until the book came out, people saw me as a maverick who was fiddling around with concert plan, but then, suddenly, the socio-political side of things blew up. The world of Carnatic music was up in arms when it saw that I had called it casteist. I think that’s when people realized the movement that was happening within me, politically.

Caste is also at the front and centre of your last book, Sebastian & Sons. Given how strongly it defines our society, is there any way of working through it, do you think?

I don’t think there is any way of working through caste. I think Ambedkar’s ‘annihilation of caste’ is the only way. The question is, how do we view caste? I view caste as an aesthetic and cultural body because of our parameters of caste—dialect, sound, physicality, face, colour, attire. So, when caste is so entrenched in how we feel, see and hear, we need to find a way to transcend our emotional habituations in order to discover human dignity and justice.

This is why I feel cultural intervention is essential if you’re discussing discrimination. The conversation has to happen in this sphere, in ritual, in habit, in faith. Let’s make it clear, I have no business speaking for the Dalit. I’m talking to people like me. We will live with the benefits of caste till we die. Sebastian & Sons was a complicated book to write. People might ask, ‘Who are you to write such a book?’ It’s a fair question. My hope is that tomorrow a mridangam maker will write a book and question all that was written in Sebastian.

Your next book, Jana Gana Mana, is slated to release in August. The national anthem is many things, but I believe you also consider it to be a song of protest …

It is! Because if there is no protest, there is no democracy. And protest is questioning. That’s all it is. If there is no idea of questioning, there is no mind. The mind is dead. ‘Jana Gana Mana’ celebrates the mind of the people of this land. And the mind is active only when it is asking questions. ‘Jana Gana Mana’ is nothing but a protest song.

Both writing and music demand a certain isolation of their practitioners. Is solitude easy to find when you are a public figure?

All this talk about great musicians who practice for seven hours in the same room is hogwash. In those seven hours, they have maybe half an hour of serious singing. The rest can be thrown in the dustbin. For me, isolation is immersion. The question is—can I immerse myself in the world I inhabit today? So, is my engagement with public discourse an immersion or a distraction? Or better still, is it a part of my music? To me, music is feeling for something that is happening around me and responding to it. If I don’t enrich myself, my music is sterile, dead. Isolation is escapism. Isolation isn’t great art.

Your mother, Prema Rangachari, and your wife, Sangeetha Sivakumar, have both greatly affected your music and activism. What is the biggest lesson these women have taught you?

I have learnt incredible tenacity from my mother. She is now 78. She has lived in a village for the last 11 years running a school for marginalized children. She just doesn’t give up. I always tell people that if they find me difficult, they should meet my mum. From my wife, it’s this idea of never trusting anything until you have worked and understood it yourself, and that we should be prepared to accept an alternative view.

T. M. Krishna at a concert by the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage in March 2021; Photo Credit: Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (Intach)

T. M. Krishna at a concert by the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage in March 2021; Photo Credit: Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (Intach)

Your position on the #MeToo debate was quite nuanced. I wanted to ask if you ever separate art from the artist?

I really don’t believe you can, but I think we conveniently do that whenever we want to, and that’s based on our own cultural habituation. For me, though, art doesn’t exist by itself. It’s a human creation. Art exists because you and I engage with it. But what do we do when we know artistes have been perpetrators of sexual harassment? Do we discard the art they have produced or do we engage with it, thereby creating an economy for an individual who has committed a crime? And beyond that economic question, there is also an aesthetic one. Is it possible for my engagement with the art to not be hagiographical in experience? These are questions I hope we can explore more.

You supported over 20,000 migrant workers during the pandemic, raising funds for 1,300 artistes while also working with the homeless. Do you think the adverse effects of COVID-19 will prove irreversible in the end?

I don’t see it reversing in the immediate future. During the lockdown, we saw this cruel irony: Migrant workers were unable to go home, while artistes couldn’t leave theirs. We have now distributed a fund of Rs 1 crore amongst artistes in 24 states of the country, but we have only scratched the surface. Most artistes in India do not have any social or economic security. The support they need can only be provided by legislation. What we really need is an NREGA (National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) for artistes and artisans. People of the arts at the grassroots level must be able to find at least 100 days of work a year. This is something I dream of.

You’ve said that your political views changed when you discovered music more fully. How can art, music in particular, help make us more socially conscious?

Art can do nothing by itself. Art is a channel by which we can feel in a way we don’t normally feel. That’s what makes art special. If music and art can become a complex conversation, then we can create layers of experience in people. They can build bonds that bind. The trouble is that we underestimate the power of feeling while we overestimate the power of data. I think if you are willing to acknowledge the power of feeling, you will realize why there is so much anger around us. You will also realize where art and music can transform society. If we make them part of an honest discussion, then we might find that art can really do things. Even if art or music changes one person, it is enough.