The Vanishing Masters of Miniature Art

Amid Udaipur’s quiet alleys, a centuries-old artistic tradition confronts a troubling future as its practitioners compete with slowing demand and digital reproductions

all photogrpahs courtesy of veidehi gite

all photogrpahs courtesy of veidehi gite

“I may well be the last generation of artists in my family. In 10 or 15 years, you won’t find craftsmanship like this anymore—no one wants to learn it,” laments Sanju Soni (43), a third-generation miniature artist whose workshop in Udaipur has become a pilgrimmage site for art connoisseurs. In the hushed stillness of his studio, Sanju hunches over a monochrome blue peacock, painted in his signature style. His neatly parted hair frames his face in even curtains as he peers through a magnifying glass, scrutinizing every detail on the 6-by-4-inch handmade sheet of paper.

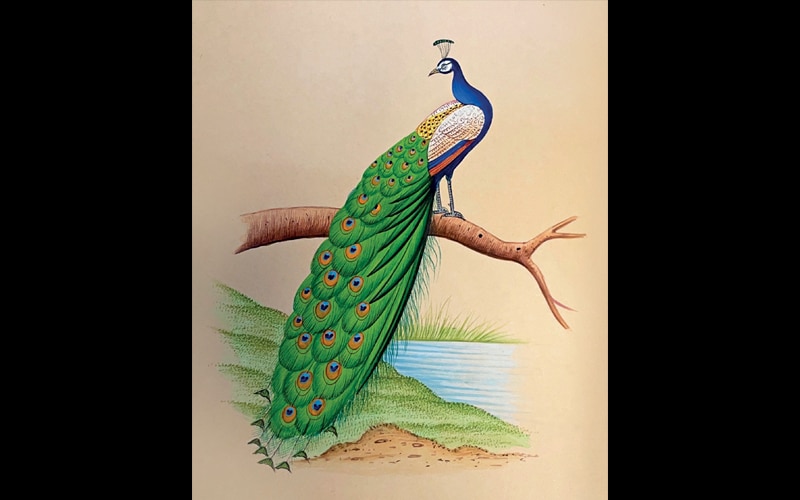

“Indian miniature paintings are typically a few inches in height and width, sometimes even as small as 15 by 10 cm—yet they hold entire worlds within them,” Sanju explains, never lifting his gaze from the plummage under his brush. “These tiny canvases eternalize mythological and historical stories with detailing so delicate, they cannot be rendered with the naked eye,” he adds.

I watch in silence as his hands—steady, patient, practised—continue. The irony isn’t lost on me: in an age of mindless scrolling through digital landscapes, here sits a man painting rich, detailed scenes on canvases no larger than a modern smartphone screen, or for that matter, the palm of a hand.

A miniature painting at Udaipur's City Palace—the result of the artist's meticulous brushwork over six weeks.

A miniature painting at Udaipur's City Palace—the result of the artist's meticulous brushwork over six weeks.

The slender alleyways and winding arteries that run alongside Udaipur’s iconic Jagdish temple, near Baddu Ji Ka Darwaza, lead to some unexpected treasures, and few are as remarkable as the modest workshops easily overlooked by hurried tourists navigating the busy City Palace road. I finally found the masters of the miniature at Sanju Arts and Nirbhay Raj Studio by following a trail of bread crumbs (and my best ‘I-know-my-art’ impression) from helpful locals and chatty shopkeepers.

Nirbhay Raj Soni (58), who apprenticed under the tutelage of his grandfather Shri Mohanlal Ji, has dedicated 43 years to innovating miniature paintings with a contemporary touch. Painting since he was nine, Nirbhay witnessed first-hand how computerization undercut demand for painstakingly handcrafted artworks, feeding faster, cheaper digital alternatives to the markets.

But changing times notwithstanding, Nirbhay has upheld his family’s heritage with some measure of success: his paintings are on display in Udaipur’s City Palace since 2003. His more notable works include renderings of the zenana mahal, depicting the daily lives of Mewar’s royal women, the rajiya aangan—an open-air kingly courtyard, and the City Palace’s lakefront elevation. He worries, however, about the future. “These days Udaipur has around 500 practising artists, but most have acquired rather than inherited the craft. Only about 50 produce high-quality work and just three to four families are able to maintain generational artistic lineages,” Nirbhay tells me.

Miniature artists create an astoni-shing level of detail on canvases only a few inches wide.

Miniature artists create an astoni-shing level of detail on canvases only a few inches wide.

Among these historic lineages, he points to Nathulal Badanji, Dhabhais Durga Lal, and Chuni Lal as torchbearers of the tradition, who are all documented in Paintings of Mewar Court Life written by art historian Andrew Topsfield. In his book, Topsfield highlights a striking depiction of Maharana Fateh Singh’s 1886 tiger hunt in Chhoti Sadri, painted by the court artist Shivalal in 1888. Another significant work that finds mention is a 1945 painting of Maharana Bhupal Singh’s birthday procession, a particularly remarkable piece that was created on the spot, painted rapidly during the event rather than composed later from memory or sketches. As one of the last ruling Maharanas before Mewar’s integration into independent India, Bhupal Singh’s portrayal in this artwork underscores the importance of royal ceremonies in the princely states, even as India moved toward independence.

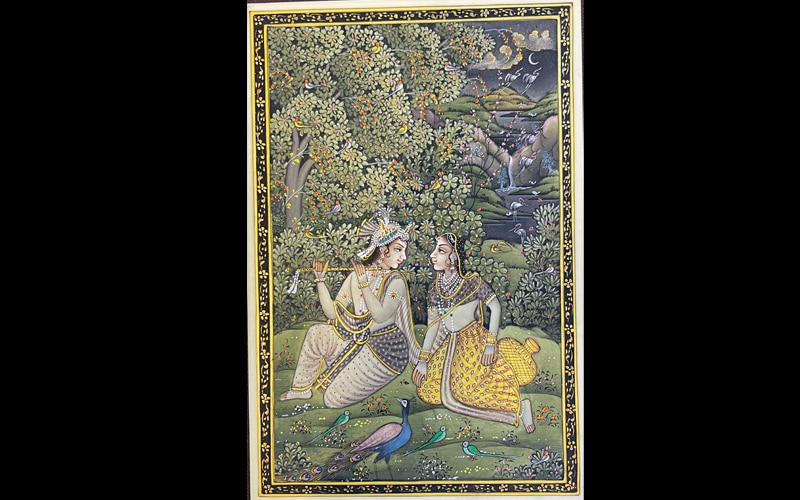

In his book Indian Court Painting: 16th-19th Century, art historian Steven Kossak describes this period as a “golden age” of miniature painting, stating that “paintings of extraordinary beauty and variety were made for the many royal courts of India”—a legacy that endured well into the British colonial era.”

Gaatha—a social enterprise dedicated to preserving and promoting traditional Indian craft—features the work of Devendra Kumar Gaud, a descendant of the chief artist at the royal court of Udaipur. Drawing from his ancestral knowledge, the platform describes the intricate process of miniature painting: “Drawn on paper or ivory, these artworks were created using ultra-fine brushes made from squirrel-tail hair inserted into bird feathers. The colours, all derived from nature, took days to prepare—red from peepal fruit, orange from palash flowers, and black from stones. The most unique was yellow, extracted from the dried urine of a sick cow.”

Paints made from lapis lazuli, malachite and other natural sources.

Paints made from lapis lazuli, malachite and other natural sources.

Back in Sanju's studio, I recall these words while studying the palette of pigments at the work desk. Sanju follows my gaze and explains, “These are all natural colours, derived from stones like lapis lazuli, indigo, red oxide, white zinc, sulphur, graphite, and malachite. I mix them with gum from the acacia tree, creating a liquid base. The stones are crushed into powder and soaked overnight in water to soften,” he goes on to share. By morning, the pigments are ready for blending and then the mixture is filtered and dried before testing. If the pigment rubs off easily, more gum and additional grinding and mixing is needed. This labour-intensive process yields colours that endure for centuries.

“While they may change due to sunlight or moisture,” Sanju notes, pointing to an old miniature depicting a royal court scene, “the painting gains a warmer, more timeless appeal.” The piece he references depicts backdrops of domed pavilions, turrets, and crocodile-filled lakes, with turbaned men and veiled women in traditional ghagras and cholis, and adorned with naths (nose rings), necklaces, and bajubandhs (armlets).

A keen eye will trace the evolution—from early works with elongated eyes to more refined contemporary compositions with softer profiles. Yet, the foundation—fabric and handcrafted paper—remains. “Handcrafted paper lasts longer—sometimes up to 700 years. The materials are entirely natural—a mix of rice powder, cotton powder, and grass powder, which make for the best quality, and made to last,” shares Sanju.

Ironically, the meticulous process involved in creating art that endures, seems to be the very thing challenging its existence. “I need a minimum of one week—or about 42 hours—on a single artwork. For detailed historical scenes, it can take up to nine months,” Sanju remarks. “This business, however, only thrives for about four months—from October to March—when European tourists visit. Indian art connoisseurs exist, but selling in galleries is difficult. It’s hard to make a living.”

Even more concerning is the absence of formal training opportunities, with no official schools—only artist families passing down the craft. Sanju says while he has shared the skill with his children, their education takes priority, putting tradition at risk. Lokesh Kumawat, a miniature artist for 27 years, also won’t pass on the skill to his children citing financial struggles. “During peak season, I earn Rs 2,000 a day, but in the off-season, even daily expenses are hard to cover.”

The depiction of Radha and Krishna is a beloved theme commonly found in miniature art.

The depiction of Radha and Krishna is a beloved theme commonly found in miniature art.

Miniature art, once a hallmark of Indian royalty, now oscillates between preservation and obsolescence in Udaipur. To keep this legacy alive, many outfits offer curated experiences and organize workshops where guests get a hands-on connection to the various forms of this tradition.

From 10th-century leaf paintings to European monastery parchments, from Mughal royal romances on silk and paper to Mewar’s epic tales on canvas, miniatures have continually adapted across cultures. In fact, as it embraces modern influences, it is making a striking comeback in surprising ways—from Tokyo’s fashion districts to Udaipur’s art boutiques, even appearing as intricate nail designs.

Even so, no trip to Udaipur feels complete without a ritualistic stop at these tucked-away ateliers. Holding frames no larger than my palm, I first understood what generations of art lovers have always known: that the most profound expressions of creativity find their way through the tiniest, most intricate strokes of genius—and nowhere, do they speak with more authority than in the miniatures of Mewar.