My Calicut Chronicles

Legends and lore simmer in Kozhikode—where every plate, prayer, and street corner serves an unforgettable story

Kappad beach, where Vasco Da Gama landed in 1498 and opened up trade between India and Europe. Photo: Shutterstock

Kappad beach, where Vasco Da Gama landed in 1498 and opened up trade between India and Europe. Photo: Shutterstock

It all begins, as it often does in Kerala, with people at a table, some conversation and food. At Hotel Jineesh, a small, bare-bones eatery in Chaliyam, a small steel plate filled to the brim is placed on a rough-hewn, wooden table. Three men, already seated, see mid-chat that there’s no room elsewhere, and quickly wave me over to settle next to them.

I slide my plastic stool seat a few inches forward to better inhale the heady aroma of the Malabar classic in front of me: kallumakkaya—freshly harvested mussels—simmering in a mix of coconut slivers and fragrant spices, partnered by a thick slice of pathri, a golden-fried, wholesome rice-flour roundel. As I wrap a chewy piece around a morsel of mussels, I see a fresh batch of batter-fried banana being carried out of the kitchen by a sari-clad, middle-aged woman, whose face brightens into a warm smile as hungry locals trickle in, eager to start the day right.

A view of the Chaliyar river, from the lawns of The Raviz, Kadavu hotel. Photo: Ishani Nandi

A view of the Chaliyar river, from the lawns of The Raviz, Kadavu hotel. Photo: Ishani Nandi

“Mussels go by different names in different districts. In another area it could be called something completely different,” explains Rajeesh Raghavan, a travel professional and local-history expert, who is guiding me through the ancient city of Kodhikode. “In some places, the word for it means something profane!” he says. With that comes the first of many revelations that sets the tone for my journey: Here, everything is deeply local and community is everything. Names could change across neighbourhoods, recipes may shift from one kitchen to the next, but the spirit remains rooted.

In the Land of Legends

If Kerala’s south were a monsoon downpour, the north would be the petrichor that follows. Unlike its well-publicized southern sibling, north Kerala remains largely untouched by the stampede of mass tourism. Its rivers, backwaters, and beaches stretch out pristine and clear, its ancient traditions pulse side by side with progress, and its people are refreshingly unhurried. It doesn’t compete with the postcard polish of Munnar or Alleppey, nor does it try to. Instead, it invites you in with the promise of raw landscapes, languid rhythms and a storied history.

It’s a warm, sticky June morning when Rajeesh and I head out to hunt for some of these stories from The Raviz, Kadavu, a sprawling, luxurious property where I am spending the night. A week-long spate of monsoon showers have just ended, I’m told, as a black cormorant grooms itself on a rain-washed frangipani tree amid the tiered lawns of the hotel, which overlooks the picturesque Chaliyar river.

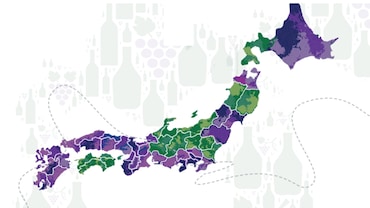

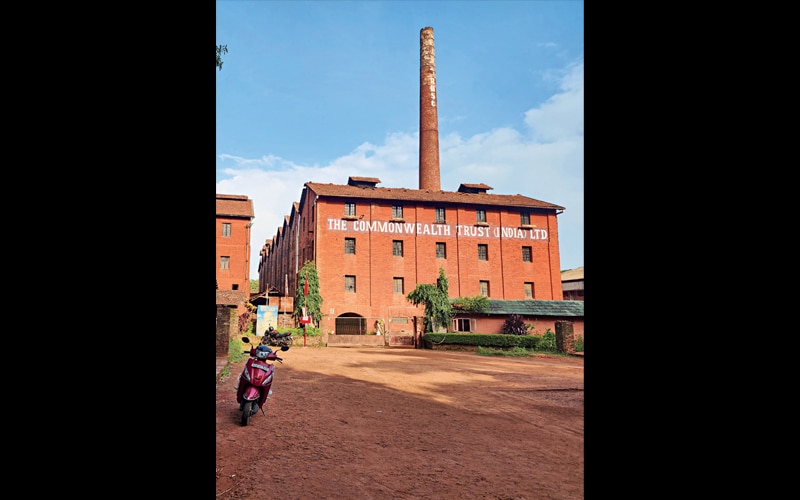

On our drive to the city, Rajeesh recounts tales from Kozhikode’s long and complex past, and with every account he points to landmarks we drive by that reflect its continued presence—a century-old British-built iron bridge still in daily use; the Commonwealth Tile Factory in Feroke, built in 1864, and the oldest, still-operating, clay roof-tile supplier in the area; the Wadiaji Parsi Anjuman Baug, an 18th-century fire temple, still managed and maintained by the Marshalls, a four-member family that is all that remains of Kozhikode’s once robust Parsi community that originally settled in this commercial hub for its promise of trade and fortune.

The Commonwealth Tile factory in Feroke is built in the style typical of England’s industrial revolution. Photo: Ishani Nandi

The Commonwealth Tile factory in Feroke is built in the style typical of England’s industrial revolution. Photo: Ishani Nandi

That same promise held true two centuries before their arrival, when Vasco Da Gama reached India by sea and opened up trade with Europe, bypassing overland Arab routes. His landing on Kappad beach, a 30-minute drive away from the city, is now a celebrated landmark and a popular tourist destination. The Portuguese explorer was warmly welcomed by the Samoothris (a title later anglicized to Zamorins), the rulers of Kozhikode, whose keen nose for business and fair practices established the city as a major spice and silk emporium through trade with Arabia, China and Persia.

Living History

Descendants of the Zamorin still live in Calicut, and ‘kings’ are still anointed, albeit as figureheads. “The last head of the Zamorins passed away at age 99 recently,” Rajeesh explains. The Zamorin of Calicut once ruled these streets. Today, their palace is a hospital, the throne room, a maternity ward, but their impact is still felt, not least in the city’s modern marketplaces, where centuries-old commerce has adapted to contemporary needs.

Embossed reliefs depicting pivotal stories about the Zamorin surround the Mananchira pond at the heart of the city. Photo: Ishani Nandi

Embossed reliefs depicting pivotal stories about the Zamorin surround the Mananchira pond at the heart of the city. Photo: Ishani Nandi

Valiyangadi Market, once the bustling heart of the city’s spice and grain trade, remains active today with wholesale dealers in rice, areca nut, and coconut oil. Nearby, Silk Street, named for its early connections to Persian and Arab textile traders, now houses vibrant sari shops and tailoring units. SM Street (Sweet Meat Street), one of the city’s oldest commercial roads, has evolved into a busy retail hub where traditional halwa stalls sit comfortably beside mobile stores and branded outlets. Once resistant to change, locals have since embraced pedestrianization and foot traffic has only increased because of it. Meanwhile, young boys lure customers and hawk samples the old-fashioned way—with cheek and charm—and sometimes unfiltered commentary.

Kozhikode’s traditional halwa was originally an Arabian delicacy.

Kozhikode’s traditional halwa was originally an Arabian delicacy.

I sample a variety of the famous ‘sweet meat’ that gives SM street its name at Shankaran Bakery, which, at 92 years old, is one of the oldest in the city. “Our halwa is originally an Arabian delicacy that we now have a monopoly over,” Rajeesh says as the man behind the counter slices off a sample from the jewel-like, soft, candied squares. “They’re made of refined flour, sugar, oil or ghee, and then nuts and a range of flavours are added to create different varieties—everything from tender coconut and honey to more adventurous ones like green chilli and pepper. But the classic ones are red and black.” We also stop at a chips shop where mounds of sliced banana, salted and soaked in turmeric, sizzle in massive cauldrons of coconut oil.

“This whole area is usually packed to the brim by shoppers and vendors. No vehicles allowed,” Rajeesh says, but I’ll have to take his word for it. My visit coincides with Eid al-Adha, and so the famous shopping hub is nearly deserted and almost all shops are shuttered. “Today is about prayer, family and feasts!” he explains.

Harmony in Heritage

In Kozhikode, faith does not stand apart—it leans in, like neighbours over a shared wall. At the 600-year-old Thali Temple, Rajeesh gestures toward the nine-tiered kalvilakku (temple lamp) with a Nandi bull on top: “It’s said that Lord Parashurama consecrated both a Shiva and a Vishnu temple in the same complex to end the rivalry between their respective followers. Nandi marks the entrance to one sanctum, Garuda marks the other.”

This spirit of reconciliation ripples outward. Two kilometers away stands the 700-year-old Mishkal Mosque, once charred by the Portuguese in 1510, rose again, “with wood from the Zamorin’s own fort,” Rajeesh notes. A little further on, the Mother of God cathedral, built on land gifted by the same Hindu ruler, shelters another prayer. Here, domes and gables, pillars and spires do not clash, they cluster.

The 700-year-old Mishkal Mosque. Photo: Ishani Nandi

The 700-year-old Mishkal Mosque. Photo: Ishani Nandi

Everywhere I go, stories permeate, not as a single, epic saga, but as a chorus of voices, each distinct and yet in harmony. The symphony includes darker stories as well. Tales of breast taxes, ground-dug food pits for lower castes, and deeply entrenched feudal customs unfold. And then there are stories of revolution: of Sree Narayana Guru, for instance, often referred to as the state’s Gandhi, who challenged caste with a gentle but seismic force, inspiring generations to rethink who they were and how they lived together.

The Mother of God Cathedral, known as Valiya Palli, is the headquarters of the Roman Catholic congregation in Malabar. Photo: Ishani Nandi

The Mother of God Cathedral, known as Valiya Palli, is the headquarters of the Roman Catholic congregation in Malabar. Photo: Ishani Nandi

As we head to Paragon, the city’s iconic restaurant, known for their impeccable food, Sunday lunch crowds and must-have tender-coconut custard, Rajeesh advises caution: “Famous personalities are snuck in through the back,” he says with a smile, “We’ll have to wait.” Indeed, the place is packed, despite the holiday, so we grab our custards and savour a scrumptious lunch of spicy prawn fry, Malabar biryani, and raw-mango-and-mint mocktail at another well-known eatery Adaminte Chayakada (Adam’s Tea Shop).

Between bites, Rajeesh tells me about a vegetarian crocodile named Babiya in nearby Kasaragod who, until his recent demise, lived in a temple pond and ate prasadam. You just can’t make this stuff up. But in ‘city of truth’ Kozhikode, you don’t have to.