- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Classic Reads

- /

The Unbelievable Mr Ripley

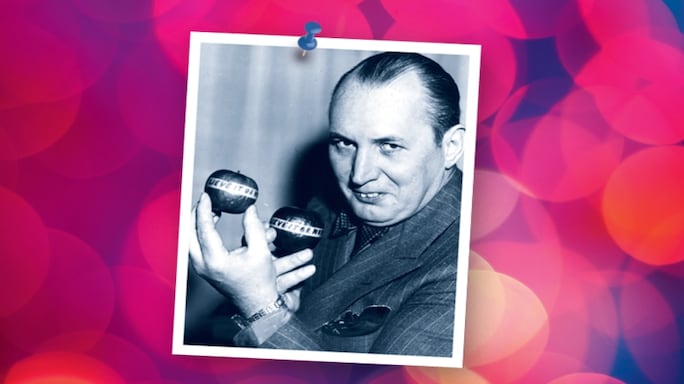

The creator of Believe It or Not had an insatiable curiosity about strange and astonishing facts

illustration: Getty images composite

illustration: Getty images composite

I first saw Bob Ripley, the creator of Believe It or Not, on a December evening more than 30 years ago. I was the brash young director-producer of a new coast-to-coast radio programme sponsored by the Hudson Motorcar Company, scheduled to go on the air in exactly 78 minutes.

We’d wanted an original and striking feature for the broadcasts and had hired Ripley sight unseen. During the rehearsal-time bedlam, I was handing out scripts, barking orders, yelling for quiet, when a large man, grinning like an embarrassed schoolboy, edged timidly through the studio door. He wore an ensemble straight out of a haberdasher’s nightmare: pale blue shirt, batwing tie of flamingo orange, checked horse-blanket jacket, fawn-coloured slacks and gleaming black-and-white sports shoes.

He gave a nervous little bow. “You’re Bob Ripley?” I asked, blinking. He blushed and nodded. Speechless, I handed him the script.

All he had to do was read a 30-second introduction to a dramatized Believe It or Not story, and then at the end, authenticate the story and say good night. It sounds sweet and simple, but by the time we went off the air that memorable night, I was a tottering wreck and Ripley was even worse. Microphone fright? It was fantastic. His script rustled like a palm tree in a hurricane. Four times he dropped it, picked it up and each time nearly knocked over the microphone stand. He mumbled his lines, but he kept on, to the bitter end.

When it was over, he reeled to the control room. “H-h-how’d I do?” he stammered. His flushed face held an expression so boyish and appealing—so earnest and honest—that my professional outrage melted. I stuck out my hand. “You need a little practice. Outside of that, you were great.”

The show stumbled along. In fact, the public liked Ripley’s awkward manner. We became friends, and before long Ripley asked me to be his personal representative. From that time, until his death in 1949, I travelled and worked with him, arranged his lectures and radio and television shows, and helped him with his motion pictures.

As I look back on it now, Ripley was probably the biggest yokel ever to succeed in show business or gain world renown as a newspaper artist. He had no polish. He was shyer than a white rabbit, painfully conscious of his buckteeth and his lack of education. But he threw himself heart and soul into everything he did, blundered through and, win or lose, he had a wonderful time.

Once in Marineland, Florida, the script called for Ripley to go down into the big saltwater aquarium in a diver’s suit, hand-feed a school of sharks and describe the experience to the radio audience through a microphone in his helmet.

“Terrific!” he said. “Where’s the helmet?”

I was amazed. “Have you ever been in a diver’s suit?”

“Heck, no,” he said. “I can’t even swim.” But down he went.

He did a hundred other crazy and sometimes dangerous things. Once he made a broadcast from a pit full of live rattlesnakes. No matter what things he tackled, he plunged into them with the tremendous zest that made them adventures.

Ripley was born in California. His father died when Bob was in knee-length pants, and he left school to go to work. All he had in the world was a knack with a pencil—and a million-dollar curiosity. In his teens he kicked around as a sports cartoonist on a San Francisco paper, then—fired for asking for a raise—headed for New York and landed a job on the old New York Globe.

One dull day in 1918 he filled a hole in the sports page with drawings of a sprinter who ran the hundred-yard dash backwards in 14 seconds. He added other sporting world oddities, slugged them Champs and Chumps, and tossed them on the copydesk.

The copy editor thought the heading was weak. Ripley then changed it to Believe It or Not.

“That’s better,” the editor said, and sent the material to the composing room.

Believe It or Not caught on. The Globe began running it twice a week, then daily, and Ripley cast around for oddities outside the field of sports. His mail increased. He accumulated a staff—two secretaries and a researcher. In 1923 he moved over to the New York Post.

Rip always said that out of his tens of thousands of cartoons he owed his fame and success primarily to two. In 1927, a few weeks after Lindbergh’s flight to Paris, Ripley ran in Believe It or Not a drawing of the Spirit of St Louis winging across the sea. Underneath was the caption: “Lindbergh was the 67th man to make a non-stop flight over the Atlantic Ocean.”

The day the cartoon appeared, the Post switch-board sizzled for hours. Ripley received more than 2,00,000 telegrams and letters, every one a scream of protest. He was in seventh heaven. He pointed out that before Lindbergh, the Atlantic had been crossed by two Englishmen in a heavier-than-air craft, by 31 others in an English airship and by 33 Germans in a German airship.

Then in 1929 Believe It or Not made the astonishing announcement that the United States had no national anthem; what Americans sang instead was in reality an old English drinking song. How come? Francis Scott Key wrote the words to ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’, then put them to the music of a rousing tavern ballad which he had discovered in a songbook. More than five million indignant letters funnelled into Washington from every state. In 1931 Congress rectified the oversight and formally declared ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’—words and music—to be the US national anthem.

When William Randolph Hearst saw the first book of Believe It or Not cartoons he sent a two-word wire to his King Features Syndicate: “Hire Ripley.” Overnight, Ripley’s income soared from $200 a week to $1,00,000 a year. Suddenly he was the highest-paid, most widely-read cartoonist in the world. He bought a rambling 29-room house on an island in Long Island Sound and had the time of his life cramming it with Aztec masks, Buddhist shrines, the shells of man-eating clams and other exotic curios.

But he never sat back and played lord of the manor. He was the hardest worker I ever knew. By 6:30 every morning of the year, he was at his drawing board. He never paid for an item, people from all over the world sent him suggestions. In addition, a full-time assistant dug up historical oddities. Ripley himself made the drawings and wrote the captions. He was a fanatic on accuracy. Every item had to be verified, witnessed, notarized.

Much of his material he gathered first-hand. Mention some distant curiosity of person or place, and his eyes would light up. He’d take a deep breath, as though he could already sniff the trade winds, and start packing. He’d toss his drawing materials into one suitcase, travelling gear into another, and take off for the ends of the earth.

Once he heard about a mountain-top monastery in Greece that one could reach only by being hauled up a 300-metre cliff in a wicker basket. So he went to see it for himself.

I remember when he heard about the Bell of the Maiden, outside of Tartar Gate of Peiping (now Beijing). It was supposed to be the largest hanging bell in the world. The legend was that in order to satisfy the emperor’s wish for the sweetest-sounding bell in China, the bellmaker’s daughter threw herself to her death in the molten bronze, just before the bell was cast. Ripley travelled all the way to China to see the bell and sketch it.

Another time he heard a fantastic story about some German scientists who froze to death in the middle of Africa. Soon he was on his way to the Belgian Congo. Sure enough, he found the story was true. In 1908 an expedition of 20 men had died of exposure at –51°C on the glacial slopes of Mount Karisimbi, a volcano only 160 kilometres from the equator. He hired a plane and flew over the place.

The years swirled by for Rip in a montage of trips, radio shows, lecture tours, television programmes—and very little rest. One night at a party at his house just after World War II, he and I were sitting to one side, talking. He looked tired. He was in his 50s and some of the snap was gone from his brown eyes. “Rip,” I said, “why don’t you quit and take it easy?”

Thoughtfully, he picked up a Canton ivory ball—one of those hollow, filigreed balls within balls—that had taken a Chinese craftsman a lifetime to carve. He turned it over in his hand. “It’s impossible, isn’t it, for anyone to have done this? Yet there it is. A hundred years ago a man sat down and devoted his life to making this ball. It’s things like that that keep me going. Proving that the impossible can happen—that it happens all around us every day. Trying to make people see that they themselves can do the impossible if they try hard enough.” He grinned, and added, as if to take the edge off being so serious, “Believe it or not.”

Ripley never did quit, even though hypertension had caught up with him. On Tuesday, 24 May 1949, he appeared as usual on the weekly Believe It or Not TV show from New York. Three days later he was dead.

Believe It or Not cartoons, drawn by others, still appear in hundreds of newspapers every day. I think of him every time I see them—also, every time I look out the window. On our lawn in New Rochelle, New York, there is a big hand-carved Alaskan totem pole. Rip sent it to me 30 years ago as a house-warming present. When I protested about what my neighbours might say, he only chuckled, “The kids’ll love it.”

Today Rip’s totem pole is a neighbourhood institution. Each year new classes of school children come to see it. Strangers stop to inspect it. It’s a landmark. And it’s Ripley. To me, looking at it is just like hearing Rip’s voice again, with the old ring in it, saying that the world is filled with romance, and there are lots of places and lots of things he’s got to see.

First published in Reader's Digest June 1959