- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Classic Reads

- /

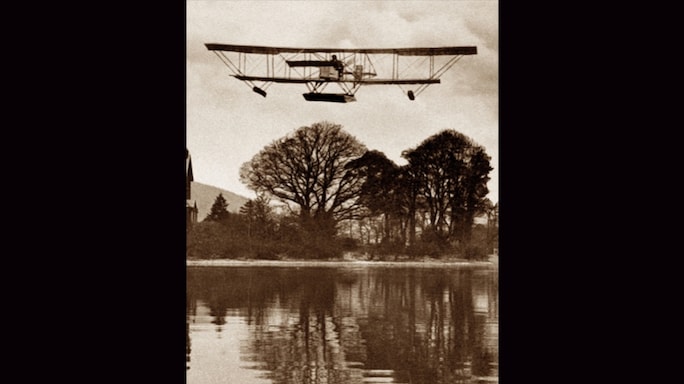

The Day We Made Flying History

On a sunny September day in 1913, the author set three world records in a homemade flying machine

Photo: Alamy

Photo: Alamy

I REALLY believed in that hydro-aeroplane I’d patched together, and I decided it was time to prove its merits by setting a world’s record or two. Nothing like circling the moon, of course—or even the earth.

The year was 1913, and all I wanted to do was to circumnavigate San Francisco Bay. And with the help of two intrepid friends, and the experience I’d acquired working with a couple of brothers named Orville and Wilbur Wright, I succeeded in writing a bizarre footnote in the history of flight.

It all started with the addiction to aviation that gripped so many young Americans after the Wrights’ first flight, at Kitty Hawk. Now at the very peak of their fame, they were being showered with adulation, often by the same people who, a few years before, had ridiculed their claim that they could fly.

Young, fresh out of school, I called in 1910 at the Wright home in Dayton, Ohio, and told Orville I had come from California to work in their flying machine factory. Within few weeks, I was settled in the wing covering department. Eventually, after learning to fly myself, and after a nearly disastrous crash, I decided to design and build a plane of my own—a safe one. For there was no question about it: those early flying machines were dangerous.

With no closed-in fuselage, they consisted of a morass of wooden struts and spars and harp-like wires supporting muslin- or linen-covered wings. A small seat, often just a flat board, was mounted toward the front, and the engine was installed in the open framework.Being of a conservative nature, I determined first to find out all I could about plane design. So, after learning from them what I could, I bade the Wrights farewell and headed back to my home in California, where I enrolled in an evening engineering course in stress analysis at what is now the University of San Francisco.

After months of work and study, my design was completed. A biplane, with two eight-foot, six-inch propellers, it had a spread of 64 feet on the upper wing, and 40 feet on the lower, with a six-foot wing width. Overall length of the craft was 36 feet. The propellers were driven by a 60 horsepower Hall Scott motor. Profanely known as a Scalding Hot, it had a habit of leaking water from its multiple joints, and had a voracious appetite for oil.

All the engineers to whom I showed the drawings laughed. For the only time in my experience, the experts were in agreement: My flying contraption would never leave the ground. Undaunted, I managed to scrounge some lumber and soon erected a small shed in our backyard. Here I worked day and night, using crude equipment that a modern mechanic would laugh at, until my plane was completed. It boasted an extra safety device: I cut an old trouser belt in half and riveted each end to the board seat. For all I know, this was the world’s first seat belt. And the machine flew!

So pleased was I with it that, after some encouraging trial flights, I decided the time had come to prove the new plane’s merits to the aviation world. I’d read that a Frenchman, Henri Fabre, had pioneered water take-offs and landings in 1910, and that Glenn Curtiss had built a seaplane the next year. So why not, I thought, substitute a pontoon for my wheels and thus gain an unlimited takeoff runway? Improved landing fields were non-existent in 1913.

As I was completing my conversion, I heard that a new type of licence was going to be issued exclusively for seaplane fliers. On 9 February 1913, I took my licence tests and was awarded Hydro Aeroplane Pilot Licence No.1, the first in America and perhaps in the world.Then, bright and early on 28 September—after a spring and summer of painstaking preparation—I felt myself ready to make aviation history. Two officials of the Aero Club of America, an affiliate of the prestigious Federation Aeronautique Internationale, calibrated and sealed the barographs for checking altitude, and my two passengers were weighed in. (The FAII weight rule stated, if passengers were carried in a record-breaking attempt, they must each weigh a minimum of 65.7 kilos. My two didn’t, so we had to add one kilo of ballast.)

Willing and reliable passengers for an airplane flight were not easy to find in 1913, and I had picked mine carefully. Stuart Dodge, a salesman, was the ebullient type—and a staunch friend in an hour of need, as subsequent events would prove. Arthur Knapp, a San Francisco Chronicle reporter, was quiet and studious. He had almost fanatical interest in flying and an unswerving belief in its future.

At 10 a.m., the three of us climbed into the plane. My sole navigation device was a tiny shoelace, tied at one end to a crosswire in front of me. This served as an astro and bank indicator; also, as long as it stayed straight back in flight, I would know that the plane was not side-slipping or stalling. Finally, I took aboard my secret weapon—a gallon demijohn of water—as a precaution against the leaky radiator of the Hall-Scott engine. A float gauge in the radiator would give a warning of a leak, and a piece of garden hose that ran from radiator to cockpit, ending in a tin funnel, would enable me to replenish from the jug any water that escaped.

The flight started at 10:19 a.m. Conditions were ideal: summer fogs had largely disappeared, and clouds were light, although a few film-like banks were rolling in from the ocean. A square-rigger, reminiscent of an earlier era, was coming through the Golden Gate. I gunned the engine, and we lifted off about 50 feet above the water. I did not intend to try for altitude until some of the gas and oil had been expended, making the plane lighter.

The monotonous rounds of the markers commenced. The western turning point was a buoy marking Anita Rock. Official observer Guy T. Slaughter, president of the Pacific Aero Club, had been rowed across to the rock by friends. Our eastern marker was the No. 2 shoal buoy just off Alcatraz. The other observer, Jack Irvine, watched from a launch.

Near Alcatraz, a small fog bank developed, unfortunately right between the official markers. I had to steer a slightly devious course, but we always managed to come out in the general vicinity of the turning points.

On one of the circuits, the fog around us seemed even denser than usual—and suddenly a ferry boat loomed dead ahead. I couldn’t climb over her in the short distance remaining, so I threw the plane into a steep bank and made the fastest turn I had ever made, either before or since. The plane’s tail missed the smokestack by inches; our backs were washed with the hat of passengers.

From then on, low flying lost its appeal. We started to climb for the altitude record. We were about 200 feet above the fog in bright sunshine. I wiped the perspiration from my face and began to breathe more easily. The engine was running beautifully. The blue water of the bay sparkled below. Flying was never more enjoyable.

After a bit, though, I felt some warm drops of something on my face. It was oil! I looked closely at the engine to see if the trouble was visible. Indeed, it was. The leak, a big one, was in plain sight. Even with the six-gallon reserve oil I had along for just such an emergency, our remaining minutes in the air were numbered. I thought record-breaking was for others; I was a failure.

At that moment, Stuart Dodge, sitting in the rear seat, leaned over and tapped me on the shoulder. “What can I do to help?” he asked. “Nothing. We’re licked,” I called back to him. Unless you want to climb out from and hold your finger over the leak.”

Stuart looked at the water of the bay some 700 feet below, at the engine mounted in the wide open cockpit space in front. He gulped once or twice, then made himself heard over the roar of the motor. “I’m your boy,” he shouted. “I’ll try it.”

Carefully, he crawled over my seat and past me. Arching to avoid the rudder control bar, he squirmed alongside the engine and placed a finger over the largest part of the leak, reducing the flow considerably.

With the propeller roaring dangerously close on one side, his position was cramped and fiendishly uncomfortable; he was exposed to a full blast of the wind, oil, and exhaust fumes over his face and shoulders. But he stuck it out.

Now Stuart undoubtedly had the most dangerous job on the flight, but I wasn’t exactly idle. Between flying the plane, watching the barographs, using the secret weapon, and fiddling constantly with the emergency oil feed, I had no time to be bored. Nor did Arthur Knapp, crouching behind me to offer the least possible wind resistance.

Finally, we could stand no more. All of us were drenched with oil; Stuart was blue with cold; the secret weapon was empty; there were only a few pints left in the reserve oil tank. I landed and taxied across the bay to beach the hydro.

The officials were all smiles. To our amazement, they informed us that we had broken not one, but three records. On that September day, I became the proud possessor, for pilot and two passengers, of the official American hydro-aeroplane duration record of one hour, 15 minutes, and 35 seconds, the altitude record of 75,000 feet, and the distance record of 53.9 kms.

Passengers, pilot, ballast, fuel, oil, and float weight added up to a total of 397 kilos. Today, 58 years later, despite all the improvements in the art, I know of no one who has flown with a greater weight with only 60 horsepower.

And as I read about our historic moon rockets and the giant thrusts that send them on their 3,82,500-km journey to the moon, I like to think that our flight over San Francisco Bay was one small, hesitating step toward man’s conquest of space.

Editor's Note: Adolph Sutro left aviation shortly after his record-breaking flight, and had a successful career in the real estate business in California. At the time this story—which won the Reader’s Digest First Person Award for outstanding and unusual true story and personal experience—was first published, Sutro had retired and lived on the Portuguese island of Madeira with two dogs, five cats, one crippled duck and a pet spider named Pilota II.

First published in Reader's Digest December 1971