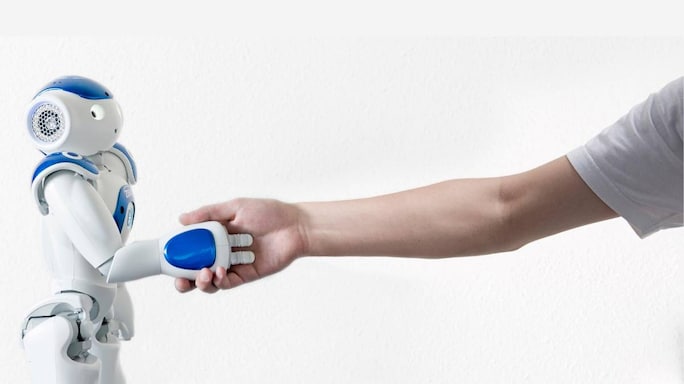

Say Hello To Your New Carer ...

The robots are coming—to look after us. And they are already helping out in nursing homes and beyond

Robot Zora is a valuable addition to conventional care. (Photo courtesy zorabots.com)

Robot Zora is a valuable addition to conventional care. (Photo courtesy zorabots.com)

Justin Santamaria moves his fingers across his iPad and suddenly the creature comes alive. The size of a baby, Zora rises from the floor onto her feet, flexing her white plastic limbs joint by joint. She stands there, her eyes round and appealing, and the five elderly ladies seated in a semicircle in front of her are full of anticipation.

“She’s giving me the eye,” laughs a lady in a wheelchair. But that’s impossible, because Zora is a robot. Since February 2019, the management of this nursing home in Paris’s 15th arrondissement have been using her to complement the care they offer their elderly residents.

Zora leads her class through a gentle workout. She moves her head up and then down to her chest, then from side to side, all the while accompanied by calming music. Her five students follow her every movement.

The next exercise gets the participants working their arms. Everything, including Zora’s speech, is preprogrammed by Justin on his tablet. But Justin is no mere puppetmaster. He is a specialist fitness instructor for the elderly and disabled, and while Zora shows her students the moves, Justin is free to give them individual attention. He walks over to a lady in a wheelchair and encourages her to stretch her arm fully. “I know you find it difficult,” he says sympathetically. He explains to the group that circling their arms will help with picking things up. The members of this chair-based gym class at Villa Lecourbe obviously adore Zora. All have poor mobility, some have cognitive problems, too. But they do as Zora tells them and when she—they always refer to the humanoid robot as a ‘she’—plays ‘La Vie en Rose’, they sing along, smiling.

“It’s like a toy,” one 90-year-old lady says after the session. “It’s like being a child all over again. At our age we have a lot of childhood memories.” “No one has the impression they’re working,” volunteers another senior. “It’s a welcome little distraction.”

But for Maisons de Famille, the chain of private nursing homes which has adopted Zora across its 16 centres throughout France, she’s much more than a bit of fun. She’s the future.

***

Robotic technology is all around us. We’re already used to autonomous devices that vacuum-clean our homes. We may even have come across robots that help surgeons operate or disinfecting bots that clean operating theatres afterwards. But increasingly, robots—especially ones that look like mini humans—are being used to help care for people and improve their quality of life.

“By introducing Zora, we are being consciously innovative in order to improve the well-being of our residents and to play our part in the search for progress in serving mankind,” explains Delphine Mainguy, director general of Maisons de Famille.

Zora leads a class at a Maisons de Famille retirement home. (Photo: Philippe Lopez/AFP/Getty Images)

Zora leads a class at a Maisons de Famille retirement home. (Photo: Philippe Lopez/AFP/Getty Images)

At Villa Lecourbe, that translates into activities that form part of the programme of personalized care for each resident. They might be exercises for strength and balance, singing, dancing, reading books or newspapers aloud in a group setting or individual sessions for those with cognitive problems who are not at ease in the company of others.

Zora might help staff coax residents to get up when they might prefer to stay in bed, or entertain a resident who dislikes having her hair done. “Her presence helps them be less anxious and more relaxed,” explains Elisabeth Bouchara, manager of Villa Lecourbe. “We try, above all, to find solutions that do not involve medication.”

Studies have suggested that Zora and other social robots add value to conventional care. But, because their use is still in its infancy, most of the evidence to date is anecdotal. Maisons de Famille tells of elderly people who don’t talk but have begun to use gestures to communicate after copying Zora.

“In one of our centres in the south of France, one resident wouldn’t allow anyone to touch him to change a dressing. Thanks to Zora, who was able to distract him, he finally accepted treatment,” says Boris Prévost, head of marketing and innovation at Maisons de Famille. “Other residents with dementia manage to concentrate twice as long in sessions where psychomotor therapists made use of Zora.”

Zorabots, the Belgium-based robotics company which designs and develops the software for several different humanoid robots, has brought Zora to life in almost 400 health-care establishments in countries including Australia, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Japan and the United States.

The company reports how one elderly person with dementia in Belgium, who no longer spoke, rediscovered their taste for conversation thanks to their robotic carer, and how another, in Paris, who had forgotten the notes in a piece of music managed to remember the whole work while interacting with Zora.

The disadvantages? Residents at Villa Lecourbe complain that Zora’s voice is tinny, a drawback for the hard of hearing. Justin Santamaria feels that the technology still needs refinements. “It’s not difficult to program,” he says, “but it takes time.”

Staff and the occasional relative were concerned at the outset that robots were being recruited to take the place of nursing staff. Not so, insists Elisabeth Bouchara. “The robot accompanies, it does not replace,” she explains. “Zora is a little character who becomes familiar with our residents, but she is programmed by a professional. On her own, she is nothing.”

Justin Santamaria agrees. “It’s another tool, like a ball or a stretchband,” he says. “It facilitates contact with residents but it’s not going to replace humans.”

***

In the United Kingdom, the borough council of Southend-on-Sea in Essex has also successfully integrated a robot into its socialcare team. Going by the name of Pepper, the child-sized humanoid is used both for elderly people with dementia and children who have Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Maxine Nutkins, the council’s community engagement manager, professes amazement at the transformation she has seen in both groups. She was present at a recent session in a dementia care home during which Pepper prompted residents to talk about their memories by asking them questions.

One lady in her 90s wasn’t participating, but when she had a one-to-one session with Pepper, she suddenly got up, started dancing, talking and holding hands with the robot, even caressing its face. Her daughter, who was present, said: “I wish you’d seen my mother before. She’s never done this. This is unbelievable.”

But, Nutkins has seen the most benefit with children who have ASD. Pepper goes into two schools for children with special educational needs and runs creative writing workshops. The robot is programmed with information about each child; they are thrilled that Pepper knows about them.

“The children are captured straightaway,” says Nutkins. “He encourages them to communicate and tell Pepper more. He motivates them to maintain concentration. No one gets distracted.” Soon the children are working together, crafting illustrated stories based on their own experiences and the things that are important to them. All too often they are unable to communicate these passions to others, let alone work in a team.

Programmed to help: Pepper (Photo: softbankrobitics.com)

Programmed to help: Pepper (Photo: softbankrobitics.com)

Thanks to Pepper’s creative writing sessions, Jacob, one teenager with ASD, has undergone a remarkable metamorphosis in the space of a year. To begin with, he would hide under headphones and rarely speak, but now he is a confident business student at a local college. “He’s a busy young man,” says Maxine Nutkins. “And that’s great, because he wasn’t a busy young man before.”

Nutkins believes the value of Pepper lies in the fact that the robot does not have human emotions that it might communicate unconsciously and which might put people off.

“There’s no pressure—that’s been one of our main observations,” she says. “Pepper is consistent. If you’re finding it hard to engage with Pepper, Pepper’s not going to pressure you to talk. Pepper will still be there two hours later with the same offer, speaking in the same tone of voice, still looking at you, still engaged with you—and that is really important for these young people.”

Professor Daniel David is head of the department of clinical psychology and psychotherapy at Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca in Romania. He agrees with Nutkins’s observations. “In the case of ASD, there is an openness for interaction with artificial beings and technologies, often more so than in interacting with humans,” he says.

Professor David believes that robots’ contribution to the treatment of mental health issues could go further still. Rather than the so-called ‘Wizard of Oz’ method used both for Zora and Pepper, where operators have to program the robot’s actions and reactions, he is working on a European Commission-funded project to develop a supervised autonomous robot to work with children who have ASD.

“We have already used it in real-life settings in about 10 centres in Romania for 79 children with ASD with good results,” he says.

***

His team have been using two robots. One is a soft, elephant-like robot called Probo that models communication skills, such as asking for things and saying thank you. The other is called Nao. Outwardly identical to Zora, but driven by different software, Nao is used for role playing so that the children learn how to imitate, take turns and develop other social skills.

Programmed to help: Probo (Photo: Vrije Universiteit Brussel)

Programmed to help: Probo (Photo: Vrije Universiteit Brussel)

The exciting thing about this work is that it is aimed at developing the next generation of robot therapy, using artificial intelligence. Robots will be able to learn from their experiences in order to assess behaviour and select the appropriate therapeutic response. They will also act as a diagnostic tool by collecting data during sessions with a child. The project team hope to publish their findings shortly.

Professor David is convinced that robots have a role in the future of mental health treatment, whether for children with ASD or for elderly people and other adults who need emotional and cognitive support at home when therapists aren’t available.

“Technological development is inevitable and robot-based technology is unstoppable,” he says. “That is why psychologists should be proactive and be those who design this future.”

The innovations are coming thick and fast. In Toulouse, French start-up New Health Community is developing a medical-care robot called Charlie for use in hospitals. He not only keeps patients company but can entertain them with games or dispense information from a touchscreen. There’s even a videoconferencing facility so that patients can talk to a doctor. Medical data is stored securely.

Charlie’s creator, Dr Nicolas Homehr, a family doctor, came up with the idea after his young son was seriously ill in hospital: It occurred to him that it would be beneficial for children in such a position to have a robot companion.

Meanwhile, AV1 from Norwegian company No Isolation is available to rent for children with chronic illnesses who miss a lot of school and feel isolated. The small desktop robot can go to school in their place and enable the student to join in lessons remotely thanks to its live-streaming technology.

Technology giant Samsung will shortly be introducing its Bot Care robot which will help and monitor sick, disabled and elderly people in their own homes. Bot Care is a moving, talking robot with a screen that doubles as a face with cute digitalized eyes. It can measure blood pressure, heart rate and breathing, remind users to take their medicine, tell them what’s in their diary for the day, play music and even alert family members if there’s an emergency, such as a fall.

Samsung Bot Care

Samsung Bot Care

Autonomous caregivers like this could be a boon in years to come, particularly so given that there will be two elderly people to every one young person in Europe by 2060, with more than 10 per cent of the population over the age of 80. But the founders of Zorabots insist that robotic technology is there to help and not to take over. “So-called social robots have already made all the difference by encouraging people to stay fit, by being involved in the care journey, as a tool for physiotherapy, by finding new ways of detecting pain or communicating with people with autism, for example,” says Tommy Deblieck, who co-founded the company with Fabrice Goffin.

“But robots will never replace human warmth and expertise. Even if tomorrow artificial intelligence can help with care or diagnosis, robots will always complement humans, and will only ever be an extra support for patients.”

Back in Paris at Villa Lecourbe, Elisabeth Bouchara is very happy with the way in which Zora, her “magic little robot”, has already improved the lives of elderly residents. “It was a great decision,” she says.