On Its 75th Year, Blind Relief Association Has Its Eye Towards The Future

Celebrating its 75th year of service, the Blind Relief Association stands at the brink of reinvention, expansion and more inclusion

Photo: Ishani Nandi

Photo: Ishani Nandi

On a crisp spring morning, the sun streams through a single window in a small, whitewashed room, around 5 feet by 10. A column of wooden table-chair pews line one wall while the other has single-seater desks with benches. The happy chatter and good-natured ribbing of eight 12-year-old boys fills the air until a young woman in a navy salwar kameez and multi-coloured shawl speaks in a strong, practised voice. The boisterous bunch instantly simmer down and listen with rapt attention. Some gaze in her direction, though not at her face or eyes, others have their heads bent all the way to the side as they focus on her words. Class is in session and in this one, listening is key.

The students are among the 200 visually impaired children who live, study and play at the JPM Senior Secondary School, an institution run by Delhi’s Blind Relief Association (B.R.A), which celebrated its 75th anniversary in February this year.

Founded in 1944 in Lal Kuan, Badarpur, by activists Anusuya Basrurker, a medical practitioner and social worker, along with her husband, Umesh Anand Basrurker, an engineer and freedom fighter, the B.R.A began as the Industrial Home and School for the Blind. “The centre was intended to act as a place where non-sighted individuals could not only find dignity and acceptance, but also be educated and learn trade-skills in order to become contributing members of society. The first two students—14-year-old Dayaram and 15-year-old Mualidhar—joined in 1946,” says executive secretary Kailash Chandra Pande, 73, one of B.R.A’s longest-working members. As the institute grew, it received support and visits from a number of iconic Indians including Vinoba Bhave, Dr Rajendra Prasad, Dr Zakir Hussain, Thakkar Bapa, Jawaharlal Nehru, Edwina Mountbatten, V. V. Giri and Indira Gandhi. In fact, the centre’s foundation stone was laid by Helen Keller in 1955.

Former President of India, Dr Zakir Hussain visits the children at the school, March 1968. From Simhavalokana a book archiving the B.R.A's history, released on the event of their 75th anniversary

Former President of India, Dr Zakir Hussain visits the children at the school, March 1968. From Simhavalokana a book archiving the B.R.A's history, released on the event of their 75th anniversary

Since then, the B.R.A has burgeoned into a school for visually impaired boys from nursery to class 12, where lodging, academics (under the CBSE board curriculum), sports, arts and music classes, study materials and assistive devices are provided at no cost. There is also a training centre for teachers of special-needs children, a vocational programme, a special-care unit for students with additional disabilities, an adult education programme and a multi-skill programme, where non-sighted adults without primary schooling learn skills such as book-binding, paper craft, candle-making, soap-making, among others. Each venture is built on the philosophical foundation of equality, self-reliance and sensitive, not special, treatment, for all.

23-year-old Komal, a teacher at JPM Senior Secondary School, in class with visually impaired students

"‘To help the visually impaired help themselves’ is the belief that underlines all our efforts. Our ultimate goal is help non-sighted people become self-sufficient so that when they step into the world, they are able to provide for themselves with dignity and confidence," says 45-year-old Radhika Bharat Ram, joint secretary of the B.R.A.

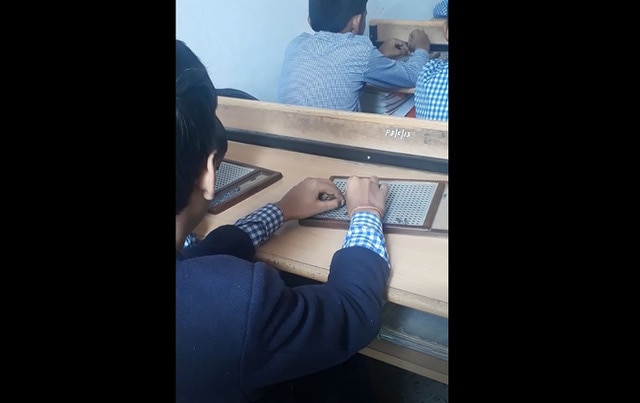

Back in the classroom, today’s lesson is maths. “Manish is very clever. The summer months are almost here so he opens a juice stand,” the teacher, 23-year-old Komal, says. Her words are fast-paced yet enunciated clearly. “He charges Rs 75 for every glass of juice he makes. Six boys each want a glass. One of them pays with a 2000-rupees note. How much balance should Manish return?” A low jibber-jabber ensues and fingers meticulously work Taylor frames—wooden square boards with perforations, into which small pencil-lead-like posts are fitted to represent the number and calculation.

A student using a Taylor frame, a calculating device for the non-sighted, to solve a math problem

A student using a Taylor frame, a calculating device for the non-sighted, to solve a math problem

When Komal calls time, those who got the correct answer are made to explain the process out loud. One gets the answer wrong, and Komal asks his neighbour, who got it right, to help him. “Questions are built around real-world activities to introduce relatable examples that they can apply to daily life. Also, peer tutoring is important—every child helps those who are weaker, and gets valuable practice in return. It also helps build responsibility and conscientiousness. And the help they offer is not only related to schoolwork,” she says, after the students are given leave for break-time.

Indeed, as we speak, two boys, much younger than the ones attending the class, wander in. One holds a cane, the other grips the cane-holder’s shoulder. They’re not sure which class they should be in. Komal walks over and gently tells them which room to go to. The two head off, guiding each other as they walk the halls. “All students are oriented with the floors so they can make their way around independently, but many move around in pairs for support. Often those with partial vision help those with none,” Komal explains.

Between life skills, academics and vocational learning, the school builds a strong foundation for promising futures. “A number of our students have gone on to become successful professionals in various sectors—some have continued their studies or are teaching at the university level, some work in banking, some are proficient athletes; we even have a volunteer-led Japanese language programme, where five ex-students are now at advanced levels,” Pande describes.

The B.R.A has also made great strides on promoting sports for the visually impaired. “In 1982, we organized the first national-level sports meet for the blind, with students from all over the country invited to participate. This event now takes place every two years. We also felt there should be an official body separate from the B.R.A, so we established the Indian Blind Sports Association in 1986. Some of our athletes have competed and won at the international level as well,” Pande adds.

A cricket match at JPM school

A cricket match at JPM school

The items manufactured year-round by the vocational-programme trainees, particularly candles, are a major draw at the hugely popular Diwali Bazaar, an annual seven-day event organized by the B.R.A to help raise funds, generate awareness and offer a space for NGOs (some at no charge) to spread their message and sell products. A major city event in Delhi, the Bazaar hosts nearly 250 stalls offering a wide array of goods, performances, food and enjoys major patronage from Delhi-ites.

A paper-lantern kiosk at the Diwali Bazaar organised by B.R.A.

A paper-lantern kiosk at the Diwali Bazaar organised by B.R.A.

Poised for reinvention in its platinum jubilee year, the B.R.A has many more milestones planned for the upcoming years. “For us, the future is marrying our programmes with current technologies, new training programmes and courses, new career paths and more collaboration with industries, for better job placements, as well as stronger government support by way of disability-friendly policies,” says Bharat Ram. While the school is currently only for boys, the B.R.A plans to include more visually-impaired women in their adult programmes, and are, in fact, building a new women-only hostel.

“There are many challenges to overcome, one of the biggest being lack of acceptance of the visually impaired, which we strive to change by teaching the sighted to come from a place of empathy and not pity,” Bharat Ram adds. “But no matter the obstacle, the ability to deal with them, find solutions, and innovate is easy when you work with people as selfless, humble and dedicated as the team at B.R.A.”