- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Bonus Read

- /

My Family's Secret Past

Mysteries swirled about my grandfather, but no one would talk to me about him honestly. Finally, I decided to find the answers on my own

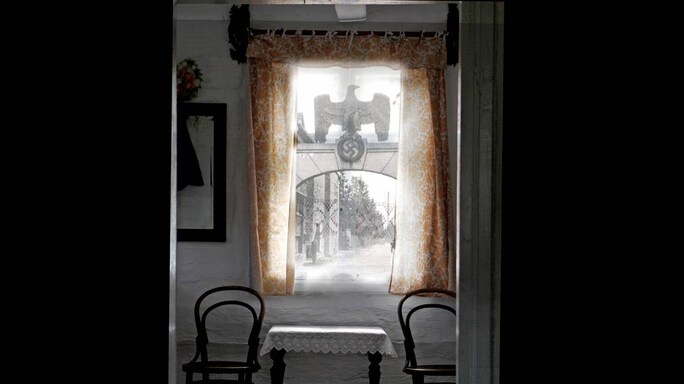

Photo Illustration: (inset) Courtesy of the US Holocaust Museum; (background room picture) © Brian Bujalski/Shutterstock

Photo Illustration: (inset) Courtesy of the US Holocaust Museum; (background room picture) © Brian Bujalski/Shutterstock

Berlin, 2010. The cold rain hung heavy in the air as I made my way down a wide empty street on the southern outskirts of Berlin. I had just one day to spend at the German Federal Archives. As I stopped to read the street sign, my troubled heart battled with my will. Wasn’t this a betrayal of the family? After months of struggling with the idea, I had decided that I must learn about Opa, my mother’s father. As none of my family would ever be willing or able to tell me the whole truth, I had to find it myself.

I approached the front desk. “I am looking for information about a particular person,” I said.

A fresh-faced young man asked, “You want to know about a family member?”

“Yes, my German grandfather,” I said. “I was born in Brazil, and I believe I was never told the real reasons for my mother’s family’s presence there,” I added.

“I understand,” he said, the sharp blue outlines of his irises softening.

He took the slip I had scribbled on, stood up energetically, and typed my grandfather’s name into the search engine of the workstation behind him.

“There is only one record in our archives under that name,” he said. “They are Ahnenerbe and other papers. Most likely they contain information about your grandmother too. I’ll have them copied and sent to you. There are about 100 pages.”

Oma? Why would my grandmother be in these papers?

I folded my hands to stop them from shaking. “What does this say about my grandfather? Was he in the SS*?” The archivist suddenly realized I didn’t understand the meaning of Ahnenerbe.

“Yes,” he said. “Ahnenerbe was an organizational part of the SS.”

As I walked out, I imagined opening the documents and finding they were not about my grandparents. But in my heart I knew it was true. These people were my very own.

A Troubling Silence

I knew Opa only through a few photographs. He remained in Brazil, a world we left behind when I was three years old. He passed away when I was nine. I was as unaware of his death as of his life. It wasn’t uncommon that relatives faded in families. The difference with Opa was that his fading was not only total, it was mandatory.

Father and Mother transplanted the family from one country to the next. We sailed through them all on an island of German tradition, even though Father was American. Many times as a young child I had visited my grandmother, Oma, in her apartment in Baden-Württemberg in south-western Germany. The table was always elegantly set, with a smaller tablecloth overlaid like a diamond on a larger one, and the gold-rimmed plates framed by sterling silver cutlery with a stag engraved into the grip.

These items were what remained of a turbulent family history that no one wished to discuss. Raising it elicited an angry exchange of words between Oma and her daughters. Mother’s words were always the sharpest, and when she wielded them, everyone fell silent. My American father would intervene by suggesting a stroll in the park. All my sister and I wished to do was to escape the room.

Julie Lindahl's grandfather is seen in the dark coat in the foreground. He joined the SS in 1934. (Photo courtesy of Julie Lindahl)

Julie Lindahl's grandfather is seen in the dark coat in the foreground. He joined the SS in 1934. (Photo courtesy of Julie Lindahl)

I commenced my master’s degree in international affairs at Oxford in 1990. During my scholarship year in Germany the previous year, the Wall had defined my studies. Now it was gone. Suddenly, the dormant history behind the Iron Curtain had begun to mill with life. I could feel there was something very personal about this event. Opa had been a farmer in occupied Poland during World War II. Mother was born there. What were my grandparents doing there? This wasn’t their original home.

As my studies progressed, a picture I preferred to deny began to form. Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, an early phase of the war. What if Opa had been one of the invaders?

During a visit from Father at Oxford that year, I asked him, “What did Opa do during the war?” Father responded abruptly. “You must never raise that subject again,” he said. He cast a look of disappointment at me I had never experienced from him before. My heart plummeted.

The last time Father and I saw one another, years later, he had waved goodbye and shouted, “Take care of my grandchildren.”

After his passing, I fell into depression. Shame wound its tendrils around me and my family. But to take care of my children, I had to take care of myself, and the only way to do that was to cut away the tendrils and go to their roots.

“Take time to attend to this,” my husband said. In order to fulfill my last promise to Father, I would have to break the one I had made to myself and to him years ago: never to look into the past.

Grim History

The documents the archivist sent me qualified my grandparents for membership in Hitler’s elite. There were birth dates, places of residence and a family tree going back to 1800 intended to uphold the illusion of racial purity.

In the photographs, Oma smiled at the camera. The earlier photographs of Opa revealed a defiant young rebel, in the tailored tweed jacket, jodhpurs and polished high-cut leather boots typical of his Hamburg middle-class origins. In later photographs, the lapels of Opa’s jacket were wide and proud, with ample room for the insignia of the party and the SS.

He had joined the party in 1931; membership in the mounted SS followed three years later. Throughout the war, Opa and Oma had resided with their family in western Poland where they, as members of a new elite, spearheaded the creation of the Reich’s model blonde province, the Warthegau.

On a cold, wet evening in December 2012, I made my way down the two-lane road that once had been the main route north out of Hamburg. I was headed to the inn that Opa and Oma had settled in with their children some years after the war.

At the reception in the illuminated castle-like house, the mayor, whom I had notified, presented himself and Herr Schuhmeister, a contemporary. I recognized the dark beams of the restaurant from family photographs. At the table, the engraved stag on the silver cutlery gleamed in the candlelight. I lifted the dessert spoon and examined the engraving. It was the same cutlery as Oma’s.

“Is something the matter?” asked the mayor.

“No,” I said. “I recognize this symbol.” This triggered a flood of storytelling by the mayor and Schuhmeister, who revealed that he had once fallen in love with one of Opa’s four daughters.

“The lady of the house dared not raise her head and was very quiet,” he said. “One day the girls told me they would have to leave.”

The mayor reached for his portfolio. “I have some documents that may be of interest to you,” he said. He placed the papers on the table.

Back in my hotel room, I opened the folder and read the testimonies of villagers who remembered Opa as a paranoid tyrant who kept his revolver by his side. Opa maintained strong connections to his former SS network. On days when the parking lot was filled with Mercedes-Benzes and the inn was closed to the public for exclusive hunting weekends, the locals knew.

The townspeople were without doubt about Opa’s motives for suddenly departing for Brazil in 1960. By the time Adolf Eichmann** was captured in May of that year, the unofficial amnesty of the 1950s made possible by the exigencies of the Cold War was over. While Chancellor Konrad Adenauer’s Christian Democratic Union had campaigned on “a quick and just denazification”—a contradiction in terms—a decade later the government could no longer resist the pressure from outside the Federal Republic to bring at least some perpetrators to trial. Eichmann’s argument about following orders fell on deaf ears. Opa must have felt the figurative noose tightening.

Julie Lindahl, aged 2, pictured with her grandfather in Brazil (Photo courtesy of Julie Lindahl)

Julie Lindahl, aged 2, pictured with her grandfather in Brazil (Photo courtesy of Julie Lindahl)

The next morning, I drove to the tiny town that was the site of an estate Opa had acquired in 1937.

Long orderly horse barns flanked a brick mansion covered in red creeping vines. Even in the rain, I could appreciate the grand vision.

“At the turn of the century the kaiser established a horse-training station for the imperial cavalry across the whole area, and this was its centre,” the widow who lived there told us.

“Do you know anything about the pre-war or wartime occupants of this house?” I asked.

“I don’t know anything about that,” she said.

Denial

“So, tell us more,” said Oma, her ancient eyes still sparkling with the curiosity of youth. “What adventures did you get up to in Hamburg?”

Oma was two years shy of a century, but her mind retained its sharpness. She had endured depression for many years and continued to suffer from nightmares and an uncontrollable blinking condition. My mother’s sister, Auntie Best, had taken over as her caregiver.

I presented Oma with a Christmas arrangement I had purchased at a handcrafting boutique near the brick mansion. She read the label out loud.

“Why, your aunt was born there before the war!” she exclaimed.

“Yes, I know,” I said, uncertain as to how I was going to handle this conversation. “I can see why Opa went for that place, with all its past connections to the kaiser and his horses. Opa liked horses, didn’t he?”

“Horses?” she ridiculed. “We never had anything to do with horses.”

“But Opa liked riding. You said so yourself.”

“You’ve got things very mixed up, child,” said Oma, who seemed a thousand miles away from me.

I rose to make myself useful in the kitchen. When Oma called for me to come back, I decided to face her with the question that the documents had already answered. Acknowledging facts must surely be better for all of us.

As I sat down across from Oma’s armchair, she had already launched into memories of Poland. “We lived a beautiful life there,” she said. “But we had to work to make it so.” Her tone changed abruptly, and she looked sternly at me. “Those lazy Poles had no idea what an honest day’s work was until we arrived and organized things.”

I found it impossible to simply listen and interrupted her monologue. “Oma, Opa was in the SS, wasn’t he?”

“No, no,” she continued, dismissing my suggestion as outlandish. I slumped in my chair. The blow of being lied to was nauseating, and my head was immediately gripped by the most painful headache. “Had he not done as they told him, they would have strung him up, you know!” My head nodded unthinkingly. These were not the insane mutterings of an old lady. Oma had made a desperate effort to justify a lie.

That evening at a local café with my beloved Auntie Best, I asked her, “Who was Opa?”

My aunt continued to stare downwards, circling her finger around the base of her wine glass. “I never had any problems with him,” she said. “Although we had to work hard at the inn, we got most things we wanted.”

She heaved a sigh, wishing that the mild prelude of what she had to say didn’t have to be over. Aunt Gise, her older sister, had always been the last to finish up work in the inn at night. She was pretty—blonde and blue-eyed—and so Opa had touched her. Besides this, Oma’s life with him had been terrible. He drank and couldn’t keep his hands off other women.

Auntie Best stopped speaking. It was time to retreat back into the confines of the family’s pact. “Now we shouldn’t stir all this up any more,” she said. That night, as I lay sleepless, many things became clear to me. Opa had taken the violence of war home with him and unleashed it on his own family. How could Oma continue to live with such a man?

A document reflecting the ‘Blood and Land’ ideology from the Farmers Association of Pinneberg, where Julie's grandfather joined the Nazi Party in December 1931 (Photo courtesy of Julie Lindahl)

A document reflecting the ‘Blood and Land’ ideology from the Farmers Association of Pinneberg, where Julie's grandfather joined the Nazi Party in December 1931 (Photo courtesy of Julie Lindahl)

Poland, 2012

Two years later, the Institute of National Remembrance in Pozna, Poland, provided me with accounts about my grandfather from the people to the local courts in 1946.

In the reading room, I shook archivist Robert Nowicki’s hand. “Welcome to the IPN,” he said, his energetic smile beaming down from a great height. He ushered me to a table and placed three sets of bound photocopied documents on the table.

“What do these documents say he did?” I asked.

Flipping through the pages, Robert replied, “It says he beat people very badly, was a terror to the people, called them pigs and dogs.” He closed the door, leaving me alone with the pages of testimonials in Polish.

But soon Robert was next to me again. He patted me on the shoulder and led me out of the reading room. For the next half hour in the staff kitchen, Robert listened patiently as the unplanned monologue of why I was here poured forth.

“Families where there is silence and lying are not happy—it was the same thing in the Communist time,” he said. Robert had a way of putting things that was refreshingly straightforward. “What will you do now?” he asked.

“Drive into the countryside tomorrow and see whether I can find these places,” I said.

“I could go with you,” Robert offered eagerly.

The following morning, Robert forced his tall frame into the passenger seat of the compact rental car and unfolded a map of west-central Poland. He pointed to a location about an hour east of Pozna, to a place now called Wilczyn, which the Nazis had renamed Wolfsbergen. “We will try to find estates of your grandparents—documents say there were three in this area—and maybe some eyewitnesses.” A stone dropped in my stomach. Would any of them still be alive?

A few farmhouses, some of them derelict, dotted the flat countryside. Opa and Oma must have felt at home here, the landscape similar to their home in Schleswig-Holstein, in northern Germany. Robert stopped some of the villagers passing by and returned with new information about people we could meet.

We drove to the home of Kisnewski, a 90-year-old man with thick, arthritic hands. His great-granddaughter repeated Robert’s words in Kisnewski’s good ear. Kisnewski’s eyes lit up with fear and he shouted Opa’s name, covering his head with his arms to protect himself from imaginary blows. Robert translated. “Some people are lined up against a wall to be shot … they try to escape … he is hiding in a barn watching … he is afraid.”

“We must stop! Stop this!” I pleaded with Robert as Kisnewski’s great-granddaughter took hold of the old man’s arms and calmed him.

I had decided that we should not continue, but Robert was resolved to keep on. “There is at least one more, a Mr Januszewski.” His parents worked on one of my grandfather’s estates, he said.

Januszewski, a stocky man in his 80s, welcomed us into his home, where we sat at a dining table overlooking a garden. Robert translated. “Your grandfather beat him when he did not take off his hat, but only with the hands.” Januszewski pointed above his eye. I looked at the scar. What hand could deliver such a blow?

“Your grandmother liked her garden. Many flowers,” Robert continued. Opa had beaten the gardener many times. “Blood everywhere. He almost died. Farm manager too, when he tried to protect other workers. Always on white horse watching and making terror.”

“Not happy man.” Januszewski shook his head.

“He says if you are like your grandmother, you are an angel,” Robert said. I looked at Januszewski in disbelief. “She made sure they got medicine, treatment after beatings. Your grandfather didn’t know.”

As we said our farewells, Januszewski clasped my forearms tightly in his hands. “Be happy,” he said. “It wasn’t your fault.”

So many things suggested that Januszewski was the son of the gardener. This man, who as a child had watched his nearest having the life beaten out of them with regularity, had seen to it that the descendant of his family’s oppressor could walk free. It was the most selfless act I had ever witnessed.

***

Upon my return home from Poland, Opa’s birth certificate waited in the mailbox. In the margin of the first page was a long paragraph of swirling script that had been signed off by a Helené Schachne, a midwife who had been present at Opa’s birth. The infant had been left with her until he was three years old, when his father claimed him.

Opa’s parents came from different social classes. Their marriage, let alone parenthood together, was a violation of social norms. I opened my albums to one of the few pictures of Opa’s mother. Her pleasant face was framed by a dark bob. Leaning toward his mother to satisfy the photographer, was Opa. “He couldn’t tolerate his mother,” Oma had once said.

Suddenly, I thought I understood the unhappiness that Januszewski had noticed. I rested momentarily in the image of the deserted child, until the brutal perpetrator overtook him and defied all comprehension.

Grand Ambitions

With each day that passed, the bronze horse on the mantelpiece at home haunted me more. Mother had given the statue to me years ago and said that she had never liked it. Today as I observed the horse, I asked myself why Opa had joined the mounted SS.

Today I would meet Nele Fahnenbruck, an expert on the mounted SS, in Hamburg. We planned to visit the villages where Opa had lived before the war and to trace the impact of joining the SS on his life and family.

As we drove to the first estate Opa had taken over at the same time as he joined the SS in 1934, Nele commented, “Looks like he didn’t lose time cashing in on his privileges,” she said, with eyebrows raised. Affiliation with the mounted SS had accelerated Opa’s class journey from humble city merchant with a cabbage patch in the countryside to grand estate owner.

“After this, he purchased the imperial horse training station you haven’t seen yet,” I explained.

The property teemed with equestrians, some of them on horseback in the riding arenas and others tending to their horses in the stalls. The place smacked of order, discipline and quality.

“My grandmother said he had nothing to do with horses.“

“Your grandmother didn’t tell you the truth,” Nele said. “This has always been horse country. It’s obvious that your grandfather’s career was given a nice lift by the mounted SS.”

“Look,” she said, turning to me, impatient with my tiptoeing. “The mounted SS were Himmler’s chosen knights who would restore Germany’s honour and demonstrate its Aryan supremacy in the riding competitions of Europe, and eventually in war. Power and influence came with the job.”

After I got home, I phoned Oma to ask how Opa had got hold of the mansion and the horse-training centre they acquired in 1937.

“Ach!” she replied dismissively. “They were just a bunch of old heath farmers squatting there.”

After putting down the receiver, I looked up the heath farmers and learnt that they were persecuted as socialists by the regime. Did Oma know? I wandered through the house and stopped before the horse on the mantelpiece. I longed for it to step out of its stiff, bronze shell, graze free on the grass and shoo the flies away with a gentle swish of its tail.

Dirty War

In 1947, Opa made a declaration to the Allied military administration of his record in relation to Nazism. It was full of testimonies to his decent character and intentions, so-called Persilscheine, a cynical term for such character endorsements that referred to the washing detergent Persil.

The Allies regarded Opa as an extremist who had joined the party before the takeover of power and the SS in its early days. A lawyer argued he had only been interested in the sport; membership in the SS was a coincidence. The eventual classification, a category III or Lesser Offender, focused on ideological commitment before the war rather than what transpired in the occupied territories. In December 1948, Opa was dismissed as a category V: “exonerated, no sanctions.”

Flustered by these documents, I picked up a photograph of Opa as a perky young man next to a wobbly-legged foal. “What happened to you?” I asked in a shaky whisper. While I had heard the confessions of eyewitnesses, I still didn’t have a clear picture of the consequences of Opa’s engagement in the mounted SS.

In the denazification documents, Opa claimed that he had taken up his assignment in occupied Poland in November 1939, two months after the invasion. This clashed with Oma’s insistence that he had left in September.

I phoned historian Jochen Boehler, my expert on the invasion of Poland. “Some of Hamburg’s best SS riders had been incorporated into policing squadrons, which followed on the heels of the Wehrmacht to establish so-called law and order in occupied Poland,” he said. They were given instructions by Hitler to ‘close hearts to empathy’ and ‘proceed brutally’.”

His voice halted. “The consequence was that these men unleashed a war so dirty that later analyses of what happened could only describe it as the decay of man. These squadrons set the tone of life in occupied Poland, and, according to those who knew them, were themselves never the same again.”

There are records of these men who were reassigned to agriculture directly after the invasion, he said. “You say that he was eager for land. Well, this was the fastest way to get hold of it.”

“And what if he really did leave in November?” I asked.

“That’s not a pretty story either,” said Jochen. Estates and farms were raided in the early hours. The inhabitants had minutes to pack up, if they had not already fled into the freezing forests. If they attempted to return, they were usually shot. Homes were stolen, people hounded and chased and the remaining labourers beaten into submission, all from the back of a horse.

I went to bed but found no peace in sleep. Instead, I heard the agonizing sound of the unmilked cows across the countryside, their owners either driven away or shot.

Germany, 2013

I visited Oma again. She had looked the same for a very long time, the snowy white waves of hair still framing a peach-skinned face. Yet she was over 100 years old, and each time I visited her I assumed would be the last.

Over the past two days, we had continued to find other subjects of discussion over Auntie Best’s meals. In the middle of the table was a black hole of suspicion that none of us was prepared to name. I realized the time for charmed conversation with Oma was running out.

If I told Oma what I knew would it bring her more or fewer nightmares? The last thing I wanted was for her to return to the depression, and to ruin Auntie Best’s good work. As I lay in bed in my hotel room that night, I determined that I would leave an old woman in peace. Yet with her nightmares, blinking and depression, Oma appeared never to have found any peace.

My husband called. “I can’t sleep,” he said.

“I can’t either,” I admitted.

“You must tell her,” he said, sounding quite certain. “If you don’t, you will never forgive yourself. You cannot play the same game of lying if you are to have any self-respect.”

I knew exactly what he meant. All along I had pursued a story that I didn’t feel I had the right to. Fear of facing the family and of breaking their taboo would continue unless I told them the truth. After another lunch prepared by Auntie Best, I moved to sit on the footstool in front of Oma. I took her hand into mine and said a little prayer to myself. “Blame must not enter this space.” I repeated in my heart. Sensing that something important was about to happen, Auntie Best sat down in one of the armchairs.

“It is time for us to acknowledge the truth between us without blaming anyone, which is that Opa was an avid National Socialist and a fanatical SS man.”

One of the grand estates that Julie's Opa presided over during the war (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

One of the grand estates that Julie's Opa presided over during the war (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Not a window had been opened, but the air in the room was suddenly cooler. Oma’s hands retreated to her lap, and she straightened her posture. “That is correct,” she said. “He looked very smart in his uniform too. They were beautiful men. What people said about them is quite wrong. They were the best sort. People didn’t have as bad a time in the labour camps as was said. That was just Jewish propaganda!”

I envisioned myself scratching at a thin layer of dust on impenetrable ground. There had to be more. The remorse would surely come.

Auntie Best was speechless, but what could she say? She had been a small child during the war, after which a blanket of silence had been cast over the crimes of her parents. In that moment I saw what had happened in our family: Shame had been left to the next generations. Those responsible had shunned responsibility, and the unrecognized victims were their children.

“So, are they coming to get me?” said Oma, looking defiant and terrified all at the same time. The pathos in these words moved me to calm her and I shook my head. “No,” I reassured her. “In fact, a young boy whom Opa hurt remembered you as an angel because you called the doctor.”

She cut me off. “That is ridiculous!” Although her husband was long dead, the instinct to defend him was very much alive. I suspected she was still afraid of him, like a ghost that would never leave her.

“He didn’t kill anyone!” she insisted. “I was with him all the time. He only beat them,” she said, regaining her composure. “We just did the same as everyone else.” My head drooped. I had never felt as distant from her as when she uttered that “we”.

Oma spoke incessantly for two hours. Many stories were recycled. The flight to Brazil still had nothing to do with the war. Scraps of information were tossed out that contradicted other scraps. “I was in the NSV,” she said proudly of her affiliation with the National Socialist welfare agency. This organization had busied itself with spreading the corrupt idea of Aryan superiority and redistributing the belongings of people who had been sent to the ghettos and the gas chambers “to support the war effort.”

It was time to go. Realizing that we would never reach that common recognition and feeling of responsibility I had hoped for, I took her hands back into mine and stroked them with the deep pity I felt for this woman who could not be honest with herself.

“Goodbye, Oma,” I said, kissing her forehead.

Return To Poland

By now, I had visited every estate but one that Opa had taken over since 1934. The last place my grandfather and his family had lived in during the war was a baroque-style palace in Siemianice, or Schemmingen in Opa’s day, in south-western Poland. Each had been grand, but this one was beyond my wildest imagination. It was as though he had aspired to become the kaiser himself. Today the building is a forestry institute.

A man in his early 30s called Tomek, accompanied by his father, shook my hand heartily. “My grandfather was deported by the SS from here to a labour camp,” he said. “We have had to work hard to get this land back, but it is ours now.”

Tomek and his father drove Robert and me around the estate. In a vast stretch of farmland, a statue of the Madonna stood: a replica; Tomek said my grandfather struck down the original. I was ashamed to be so closely related to a person who would do such a thing.

He also told us that nearby was an unwed mothers’ home, supported by the local NSV, women like Oma. It was believed there were Jewish girls held there, and the children born to them were struck from the birth register. The rape of Jewish girls had become a standard weapon of the SS’s dirty war in the East. But fraternizing with Jewish women was illegal. Had the mothers’ home been used to cover up a problem or to run racial experiments? It was impossible to digest the monstrosity of it.

Back in the driveway, the director of the forestry institute handed us a slip, “You must visit this man. He has written about your grandfather.” As we entered their apartment, Matysiak and his wife stared at me in wonderment. Matysiak had survived Opa’s fiefdom as a boy. We sat down at a table laden with fine porcelain, tea and biscuits.

“He was an unhappy man,” Matysiak said. This is what so many remembered about Opa.

“He had a temper like spitfire,” he explained. “His wife and children just cowered around him.” According to Matysiak, towards the end, Opa turned his attention to escaping the enemy from the East. “It was the 18th of January 1945. There were many convoys passing through our town on the same route back into the Old Reich. I will never forget the mothers holding their infants, who had frozen to death.

“Your grandfather led his hay-laden carriages out a different route to avoid the partisans. They were after his head,” said Matysiak.

I pictured my mother’s frightened eyes peeping out of the hay next to her older siblings. What had this three-year-old been told by her mother, now pregnant with a brother or sister?

“We remember his wife well,” he had said, referring to Oma. “She wore the NSV pin daily and was proud of it.”

Images of Oma passed before me like pieces of a torn canvas. To the young Januszewski she had been the angel who had called the apothecary. There was the image of the stalwart NSV leader, working for ‘maternal health’ in her area. There was the pregnant woman surrounded by her four children on a freezing night in a hay-laden carriage. And there were the delicate hands that stroked mine with gentleness.

“Quiet Is the Best”

Back home, photocopied documents had arrived in the mail from an archive in Ludwigsburg. According to an interpreter for the Gestapo, Opa had collaborated in “eradications” of unarmed locals in a forested area near Wilczyn known as the site of night-time executions by the SS and local Gestapo.

With a heavy heart, I called Oma. “I must say, you went very hard at me,” she said angrily, leaving no time for offloading sadness. “I haven’t been able to sleep.” Her complaint was like sandpaper that scratched open my guilt wound, so I listened.

“You should let him and this history rest in peace. You know nothing about that time. It doesn’t belong to you!”

The ensuing conversation turned ugly as fragments of the old NSV volunteer’s memory were tossed out into open view. “Your marriage has brought genetic uncertainties into our family. I am sure your daughter is already ripe for marriage.” My husband had three disabled siblings who had died young. My daughter was only 14. Whatever did she mean?

“All it takes is one kiss and there will be children,” Oma said.

In that moment it seemed to me that the vulgarity at the core of history’s unprecedented racial experiment was laid bare. Oma had gone to a wilderness with a man she feared because she too had participated in that experiment and felt the need to hide.

“I have to go now, Oma,” I said, trying not to fall apart.

She made sure to have the last word. “Remember that quiet is the best.”

In 2014, the news came that Oma was dying. She was two months shy of 103. During the year since we had last spoken something had shifted inside me. I had talked publicly of my discoveries. By breaking an old family taboo, healing had begun. My ears had ceased to hear the echo of Oma’s hard words. Now all I knew was that a life that had survived a terrible century and was closely tied to mine would soon end. The prospect of her loss and the knowledge of her tragedy left a gaping hole in my heart. At Oma’s grave, I felt an odd sense of neutrality about the way my relationship with her had ended. My husband had been right to advise me to face her with what I knew.

***

The spring rain had begun to fall outside the window to my study. I found solace in observing the wooden statue of an angel I had placed on a pedestal in our backyard after I had learnt of the Madonna in the field that Opa had struck down.

As the water gathered in her cupped hands, I imagined that she had the choice of how to hold it: with awareness and reverence, or with fear and indignation. The former was much more difficult, because it demanded self-respect to acknowledge kindnesses and admit one’s own injustices, and the inclusion of all life. The rain intensified, insisting that we must never stop trying.

*A major paramilitary Nazi organization which implemented the planned elimination of Jews and other races

**After the war, Eichmann was convicted and executed for war crimes as the chief architect of Nazi genocidal efforts.

The author has omitted surnames and other identifying details to respect the privacy of family members and survivors.