- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Classic Reads

- /

I Knew Those Wright Brothers Were Crazy!

A firsthand account from one of the first people to hear—and initially dismiss—the news of a breakthrough that heralded the dawn of a new era

A historic photograph taken by John T. Daniels on 17 December, 1903, showing Wilbur and Orville Wright during the first successful airplane flight.

A historic photograph taken by John T. Daniels on 17 December, 1903, showing Wilbur and Orville Wright during the first successful airplane flight.

One morning in late November 1903, I left Currituck Beach Lifesaving Station and drove my one-horse beach cart down the shore to the forsaken dunes of Kitty Hawk. There was a break in the telegraph wire there and it was my job, as telegrapher and line repairman for the US Weather Bureau, to fix it. The Bureau had full Coast Guard duties then, and upon that line might depend the fate of ships driven ashore on North Carolina’s treacherous Outer Banks.

As I spliced the line I waved indifferently to two figures over on the dunes. They were the Wright brothers—two eccentric bicycle mechanics from Dayton, Ohio, who believed they were going to make a horseless motor carriage fly like a bird. They were crazy, of course.

By now all of us native islanders knew Wilbur and Orville Wright by sight. For four years now they had come to camp on this lonely expanse of sand and experiment with what looked like a clumsy kite of wood and cheesecloth. Now they came up the beach and stood watching me work.

“Flown yet?” I asked, hoping the irony wasn’t too transparent.

“Not yet,” Orville Wright said quietly. “The hurricane last month tore up our camp, and that gale the other day ripped it apart again.”

“What with all the delays, we’re just beginning to assemble our aeroplane,” Wilbur said,”but we’ll be trying it soon. We’ll let everybody around here know when we’re ready. I hope you can come.”

“I hope so,” I lied politely, “but I have to stay at the Lifesaving Station practically 24 hours a day. It’s my job to sight any ships in trouble and telegraph Norfolk. My telegrams bring the tugs down to grab ships before they can go on the shoals.”

“Really?” said Orville, with what appeared to be genuine interest.

“I have to be where the big news breaks. That’s why I can’t afford to spend much time away down here.”

“I see,” said Orville. “Well, good luck.”

I finished repairing the wire and departed from Kitty Hawk. I was anxious to get back to where big things might be taking place. The next week, on 3 December, the most sensational news story that had ever happened on the Outer Banks broke, right in my lap. A curious craft came wallowing down the Atlantic before a northeast gale. I looked at her through binoculars and suspected from her peculiar cigar shape that she must be one of the Navy’s wonderful new submarines. They were the first ones that had been proved to be practical. Two of them, the Moccasin and the Adder, had left Newport, R. I., for Annapolis in tow of the Navy tug Peoria. I guessed that the tug had lost her tows in the preceding night’s storm. The tug was now hovering about the sub as the helpless vessel rolled toward our beach. This was the kind of action I’d told the crazy Wrights about. This was my big break.

It was I who, ahead of other observers on the beach, recognized the sub as the Moccasin; I who dashed to my telegraph instrument and flashed the news to the Portsmouth Navy Yard; I who was waiting on the beach when the sub finally struck that night.

I set up my instrument on an orange crate, cut into the main line to Norfolk, and wired Admiral P. F. Harrington: “U.S.S. MOCCASIN STRANDED 11:30 P.M. ABREAST CURRITUCK LIGHT. WRECK STATION ESTABLISHED. DRINKWATER.”

For two weeks I covered myself with glory. There, her keel stuck in six feet of sand, lay the marvellous diving boat in which Miss Alice Roosevelt, daughter of President Teddy himself, had recently allowed herself to be submerged at New London, Conn. There lay the tin fish that was the No. 1 headline news of America, and not a word about her could go out to the world except through my telegraph key.

Six tugs with 12 inch thick cables failed to budge the Moccasin, and every day she remained stranded my reputation increased. In order not to miss reporting a single detail about her salvaging I fashioned a tent from an old beach cart cover and slept on the shore beside her.

By the evening of 17 December, I was a tired young man. I was smug, however. Hadn’t Admiral Harrington sent me two commendations for my alertness? Hadn’t the Weather Bureau raised my salary from $600 to a handsome $720 a year? So I was a bit irritated when, about 8:30 that evening, the telegraph wire between Nags Head and Currituck broke down and I was asked to relay to the mainland a few trivial telegrams telephoned to me from down the beach. Some duck hunters were wiring their wives when they’d be home. And there was a message from those crazy Wrights to their sister Katharine. I tapped it out: “FLIGHTS SUCCESSFUL. WILL BE HOME FOR CHRISTMAS.”

Only then did I recall that this had been the day the Wrights had invited anyone interested to come to Kill Devil Hill and see them ‘fly’. I wondered if I could have missed anything by not going down there that morning—as five other islanders, three of them buddies of mine in the Lifesaving Service, had had the curiosity to do. I decided the trip would have been a waste of time.

The news of the Wright flights I had so indifferently helped relay to the world created scarcely a ripple of attention. Of course there was that ridiculous tale the five islanders who had witnessed the ‘flying’ kept telling. The Wrights, they insisted, had flown four times in their 605-pound [300-kg] aeroplane, and on the last and longest flight had travelled 852 feet and remained in the air 59 seconds. But from the way most newspapers ignored the yarn I knew there was nothing to it.

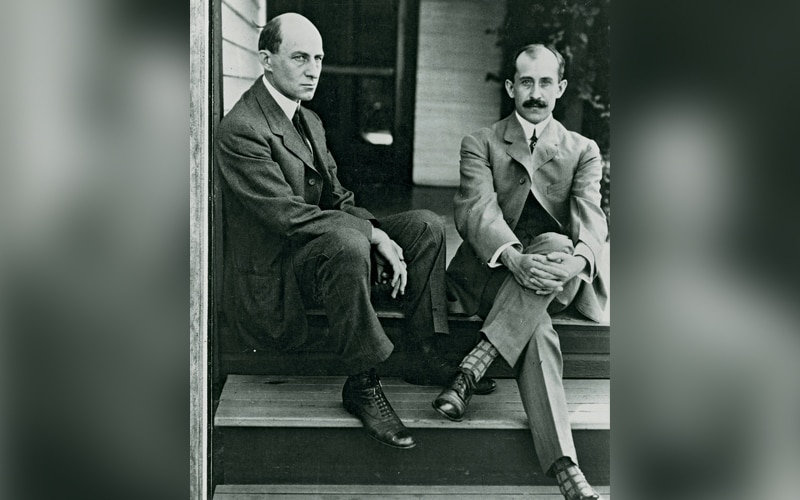

Wilbur (on the left) and Orville Wright at their home in Dayton, Ohio, 1909

Wilbur (on the left) and Orville Wright at their home in Dayton, Ohio, 1909

On the morning after the alleged flights, I found out later, only three newspapers in the world mentioned the Wright foolishness. They all printed parts of a story written by a cub reporter named Harry P. Moore of the Norfolk Virginian Pilot. Full of fiction, the account reported that Wilbur Wright had soared with bird-like ease three miles [five kilometres] out over the ocean, while Orville ran about shouting, “Eureka!” But young Moore’s story, the first to report the birth of the airplane, was no more inaccurate than hundreds of others written later by ‘experts’. And Moore was the first reporter to realize that flying was important.

Editors failed to share his enthusiasm. On the evening of 17 December, Moore tried to interest 21 newspapers in his flight story, but only five of them warmed to the idea at all. On the morning of the 18th it appeared in only the Virginian Pilot, the Cincinnati Enquirer and the New York American. That afternoon the Wrights’ hometown Dayton Daily News ran a small item on an inside page. Fred C. Kelly points out in his definitive biography, The Wright Brothers, that the editor failed to distinguish between a heavier-than-air flying machine and a gasbag equipped with a propeller, so the headline was: “Dayton Boys Emulate Great Santos Dumont.”

Most people were like me—they just couldn’t take the thing seriously. Probably the Wright boys hadn’t flown at all, we figured. The renowned American astronomer Simon Newcomb had stated that it was impossible to fly a heavier than air device. For five years I—and millions of others —continued to disregard what was happening, even though in 1905 Wilbur Wright claimed he had flown 24 miles [38 kilometres] in 39 minutes. Then, in 1908, the crazy Wrights returned to Kitty Hawk to test a so called biplane they were trying to dupe an indifferent War Department into buying for $25,000. By then I was chief telegrapher on the Outer Banks, and for reporters who came to my house at Manteo I wired the first 42,000 words of news stories on something they called ‘military aviation’. I still didn’t believe a word of it.

Over my key, the freelance reporter Donald Bruce Salley telegraphed the Cleveland Leader that he had seen the 1908 Wright machine leave the ground. The editor flashed back angrily: “Cut out the wildcat stuff. We can’t handle it.” Salley had me wire the same story to the New York Herald, which replied, “Confine yourself to facts.”

To get the truth the Herald sent its star reporter Byron R. Newton to the scene. When Newton reported he had seen a man fly, his paper accused him of faking and he was suspended from the staff. Newton tried to sell his eyewitness accounts to a leading magazine but the editor wrote him: “Your manuscript does not qualify either as fact or fiction.”

Finally my curiosity got the best of me and I set out for Kill Devil Hill to see what was really going on. My mouth gaped as I beheld a two winged contraption of split fir and cloth bear a man and a clattering engine into the blue! I rushed home, signed an affidavit to that effect and sent it to the New York Herald. Byron Newton got his job back (he later became Assistant Secretary of the Treasury).

I now began to suspect the awful truth: perhaps I had covered the wrong news event back in 1903. Perhaps I should have reported the details of the Wrights’ first flights instead of the wreck of my beloved Moccasin. I, commended for being an alert observer, had neglected to report or even to see the most significant news event of the 20th century.

Editor’s Note (1956): Alpheus W. Drinkwater, patriarch of North Carolina’s Outer Banks, is a well-known raconteur, sought out by tourists almost as often as are Kill Devil Hill and the Wright Memorial Pylon. At 81 he serves as a volunteer ground observer for the Air Force. Mr Drinkwater says: “Though always in search of miracles, people lag too far behind in their acceptance of miracles when they happen.”

First published in Reader's Digest November 1956