- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Classic Reads

- /

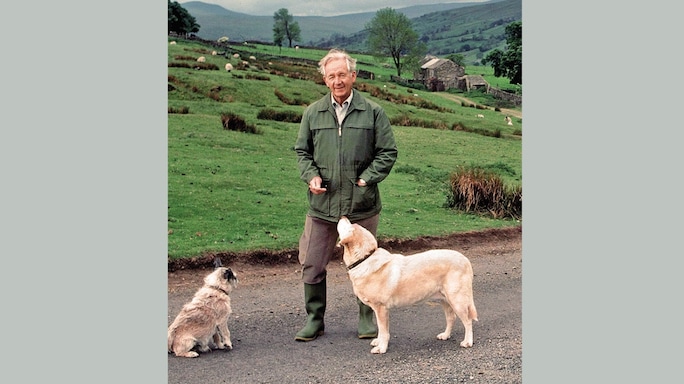

Man's Best Friends: From the Book James Herriot's Dog Stories

A love of dogs inspired this man to become a veterinarian. Here, he shares some of his favourite stories

photo © Julian Calder/Shutterstock Leash illustration by elizabeth traynor

photo © Julian Calder/Shutterstock Leash illustration by elizabeth traynor

Growing up in Glasgow, Scotland, James Herriot dreamt of becoming a ‘dog doctor.’ After earning his qualifications as a veterinarian in 1939, he found work in the rural region of Yorkshire in northern England. Contrary to his childhood dreams, he mostly treated farm animals. Still, he never lost his love for dogs, both as pets and occasional patients. In time, Herriot began to write about life as a country vet. His books, populated by delightful characters both animal and human, became international bestsellers. In 1986, he gathered together into one book stories about dogs—the animal that inspired him to become a veterinarian in the first place. Here are a few of his tales.

The Stray

If things were quiet in our surgery in the town of Darrowby, my boss, Siegfried Farnon, and I would walk across the cobbles on market day to have a word with the farmers gathered around the doorway of the Drovers Arms pub. One day, we noticed a little dog sitting up and begging in front of one of the stalls.

“Look at that engaging little chap,” Siegfried said. “What breed would you call him?”

“He’s like a sheepdog, but there’s a touch of something else—maybe terrier,” I replied.

As we drew near to him I squatted down and spoke gently. “Here boy. Let’s have a look at you.” Two friendly brown eyes gazed at me from his attractive face, but as I inched nearer he turned and ambled away. I refrained from following him because Siegfried was strongly opposed to the whole idea of keeping dogs as pets. He said it was utterly foolish—despite the fact that five assorted dogs travelled everywhere with him in his car.

While I was standing there, a young policeman came up to me. “I’ve been watching that dog begging all morning,” he said. “But like you, I haven’t been able to get near him.”

“Yes, it’s strange. I wonder who owns him.”

“I reckon he’s a stray. It beats me how anyone can leave a helpless animal to fend for himself.”

As I lay in bed that night I was unable to dispel the image of the little creature wandering in a strange world, sitting up and asking for help in the only way he knew.

Friday night of the same week, Siegfried and I were arraying ourselves in evening dress in preparation for the Hunt Ball at East Hirdsley, about 15 kilometres away. I had just managed to don the complete outfit when the phone rang. It was the young policeman.

“We’ve got that dog, Mr Herriot, the one that was begging in the marketplace. One of the men found him lying by the roadside outside of town. He’s been in an accident.”

I told Siegfried. “Always happens, doesn’t it, James?” he said. “Just when we’re ready to go out. Better go there and have a look. I’ll wait for you.”

The policeman led me to the kennels behind the station and opened one of the doors. The dog was laying very still. He had multiple lacerations, one hind leg was crooked in the unmistakable posture of a fracture, and there was blood on his lips.

When I gently raised the head, it was as though somebody had struck me in the face. The right eye had come out of its socket and sprouted like some hideous growth from the cheekbone. I looked into the dog’s face and he looked back at me, trustingly—from one soft brown eye.

“What d’you think, Mr Herriot?” I knew what the policeman meant. A quick overdose of anaesthetic and this lost, unwanted creature’s troubles would be over. I stood up. “May I use your phone?”

At the other end of the line Siegfried’s voice crackled with impatience. “James, it’s the Hunt Ball! We’ve got to go now. It’s just a stray dog.”

“I know, Siegfried, but I can’t make up my mind. I wish you’d come and tell me what you think.”

There was a long sigh. “All right, James.”

He created a stir as he swept into the station, a camel-hair coat thrown over his sparkling-white shirt and black tie. The young policeman led him back to the kennels.

Siegfried crouched over the dog, then carefully raised the head. “My God!” he said softly. Then he straightened up. “Let’s get him to the surgery.”

On the table we anaesthetized the dog and examined him thoroughly. Finally Siegfried said, “There’s enough here to keep us going till midnight.”

I looked at him across the table. “What about the Hunt Ball?”

“Forget it. Let’s get busy.”

We began on the eye. I lubricated the ball, and Siegfried manoeuvred it back into the orbital cavity. “No major damage,” he said. “We’ll just stitch it together to protect it for a few days.” Then we got the broken ends of the dog’s fractured tibia together and applied a cast. Finally we stitched the many cuts and lacerations. The most disturbing thought was that after all our efforts we would still have to put him down if nobody claimed him within 10 days.

When we finished, we carried the dog through to the sitting room on a blanket, laid him before the fire, and poured a drink. Siegfried reached down and touched one of his ears.

“What an absolutely grand little dog,” he murmured.

Two days later I took the stitches out of the dog’s eyelid and was delighted to find a normal eye underneath. “Look at that!” the young policeman exclaimed. “You’d never know anything had happened.”

But the days passed and nobody inquired about the dog or offered to take him. On the 10th day I made my way to the police kennels. Putting down a young, healthy dog is a terrible thing. I hated it, but as a veterinarian I had to do it.

“Still no news?” I asked the young policeman. He shook his head. I went into the kennel, and the shaggy creature stood up against my legs, his eyes shining. I turned away quickly. I’d have to do this right away or I’d never do it.

“Mr Herriot.” The policeman put his hand on my arm. “I think I’ll take him.”

“You?” I stared at him.

“Aye,” he nodded slowly. “We can’t give all the stray dogs in here a home, but somehow this one’s different.”

Warm relief began to ebb through me. I looked at the policeman. “What’s your name?” “Phelps,” he replied.

“Well, that’s fine, Phelps!” I had to fight an impulse to shake his hand and thump him on the back but managed to preserve a professional exterior. I didn’t see our patient again until four weeks later when the cast was due to come off. Phelps brought in his two girls along with the dog. They eagerly put their arms around their new pet and hoisted him onto the table. His wide mouth panted in delight. Phelps smiled.

“I can’t tell you what pleasure he’s given us, Mr Herriot. He’s one of the family.” I got out my saw and began to cut the plaster. “It’s worked both ways I should say. A dog loves a secure home.”

Phelps laughed and addressed the little dog. “That’s what you get for begging at the stalls on market day. You’re in the hands of the law now.”

Hesitating Steps

“Could Mr Herriot see my dog, please?”

Familiar enough words coming from the waiting room of our practice in Skeldale House, but it was the voice that brought me to a halt just beyond the door. It sounded just like Helen Alderson. I tiptoed forward and peered through the crack in the door. All I could see was a hand resting on the head of a patient sheepdog, the hem of a tweed skirt and two silk-stockinged legs.

Then a head bent over to speak to the dog and I had a close-up in profile of a small straight nose and dark hair. I was still peering when Tristan, Siegfried’s younger brother and a veterinarian himself, shot out of the room and collided with me. Stifling a curse word, he grabbed my arm and hauled me along the passage into the dispensary.

“It’s her!” he said in a hoarse whisper. “The Alderson woman! And she wants to see you! Not Siegfried, not me, but you!”

He looked at me wide-eyed as I stood hesitating. “What are you waiting for?” he hissed.

“Well, it’s a bit embarrassing, isn’t it? Last time she saw me I was a lovely sight.” I had met her at a dance, and in fact had been so drunk afterwards that I couldn’t speak.

Tristan struck his forehead with his hand. “She’s asked to see you—what more do you want? Go on, get in there!”

I marched into the waiting room. Helen looked up and smiled. It was the same friendly, steady-eyed smile as when I first met her. We faced each other in silence for some moments.

“It’s Dan, our sheepdog,” she said at last. The dog wagged his tail furiously at the sound of his name, but yelped as he came toward me. I bent down and patted his head. “I see he’s holding up a hind leg.”

“Yes, he jumped over a wall this morning and he’s been like that ever since. He can’t put any weight on the leg.”

“Bring him through and I’ll have a look. But go in front of me, and I’ll be able to watch how he walks.”

I held the door open, and she went through ahead of me with the dog. I could see by the way he carried his leg under his body with just the paw brushing the ground that he had a dislocated hip. This was a major injury, but the chances were I could quickly put it right—and look good in the process.

In the operating room I hoisted Dan onto the table and examined the hip. No doubt about it—the head of the femur was displaced.

“When will you be able to start on him?” Helen asked.

“Right now. I’ll just give Tristan a shout. This is a two-man job.”

“Couldn’t I help?” she asked.

I looked at her doubtfully. “You mightn’t like playing a game of tug-of-war with Dan in the middle.”

“I’m quite strong and not a bit squeamish.”

“Right,” I said. “Slip on this spare coat and we’ll begin.”

The dog didn’t flinch when I injected anaesthetic into his vein. Soon he was stretched unconscious on his side. I took hold of the affected leg and spoke across the table.

“I want you to link your hands underneath his thigh and try to hold him there when I pull. Okay?”

It takes a surprising amount of force to pull the head of a displaced femur over the rim of the acetabulum. Helen did her part efficiently, leaning back against the pull, her lips pushed forward in a pout of concentration.

I tried all sorts of rotations and twists on the flaccid limb and was wondering what Helen must be thinking of this wrestling match when I heard a muffled click. I flexed the hip joint. The femoral head was once more riding smoothly in its socket.

“Well, that’s it,” I said. “Hope it stays put. The odd one does pop out again, but I’ve got a feeling this will be all right.”

During the struggle with Dan’s hip, I had been able to observe Helen at close range. I had discovered that her mouth turned up at the corners as though she was going to smile; also that the deep, warm blue of the eyes under the smoothly arching brows made a dizzying partnership with the rich black-brown of her hair. I picked Dan up and settled him on the back seat of Helen’s car; under a blanket, he looked at peace with the world.

Helen called that evening to report Dan was up and walking. “Thank you so much for what you’ve done.”

“Not at all. He’s a grand dog.” I hesitated for a moment. “Oh, you remember we were talking about Scotland today. Well, I was passing the Plaza this afternoon and I see they’re showing a film about the Hebrides. I wondered if perhaps, er … you might like to go and see it with me.”

Another pause and my heart did a quick thud-dud.

“Yes, I’d like that,” Helen said. “When? Friday night? Well, thank you—goodbye till then.”

I replaced the receiver with a trembling hand.

For the Love of the Chase

Looking out our bedroom window across the weathered reds and greys of the roofs of Darrowby to the hills beyond, I could see that it was going to be a fine morning. Following our honeymoon, Helen and I had set up our first home on the top of Skeldale House. Siegfried, who was no longer my boss but my partner, had offered us free use of these empty rooms on the third storey and we had gratefully accepted; it was makeshift and spartan, but there was an airy charm.

Helen soon had the kettle boiling in our little kitchen–dining room, and we drank our first cup of tea by the window looking down on the garden. After breakfast, I went downstairs, collected my gear, and headed out for Robert Corner’s farm to treat a foal that had cut its leg.

I hadn’t been there long before I spotted Jock, Mr Corner’s sheepdog and a dedicated car chaser. The farm was at the end of a long track that twisted between stone walls through the gently sloping fields to the road below, and Jock didn’t consider he had done his job properly until he had escorted his chosen vehicle right to the very edge of the property.

I watched him now as I finished stitching the foal’s leg. He was slinking about, a skinny mass of black and white hair, pretending he was taking no notice of me. But his furtive glances gave him away. He was waiting for his big moment.

It wasn’t until I had started my car and begun to move off that he finally declared his intentions. As I gathered speed he broke into an effortless lope. That sparse frame housed a perfect physical machine, and the slender limbs reached and flew again and again, devouring the stony ground beneath, keeping up with the speeding car with joyful ease.

There was a sharp bend about halfway down the road and here Jock sailed over the wall and streaked across the turf, a dark blur against the green. Finally there was the run down to the paved road. My last view of him was of a happy panting face. Clearly he considered it a job well done.

There was another side to Jock: He was an outstanding performer at the sheepdog trials. Mr Corner could have sold the little animal for a lot of money but couldn’t be persuaded to part with him. Instead, he purchased a scrawny female counterpart of Jock. Soon there were seven fluffy black balls tumbling about the yard. Jock watched indulgently as they tried to follow him in his pursuit of my vehicle, and you could almost see him laughing as they fell over their feet and were left trailing far behind.

It happened that I didn’t return to Robert Corner’s farm for about ten months. When I finally saw the pups again they were like seven Jocks darting about the buildings. As I prepared to get into my car they peeped furtively from behind straw bales, slinking with elaborate nonchalance into favourable positions for a quick getaway.

When I revved my engine and shot across the yard, the immediate vicinity erupted in a mass of hairy forms. On either side of me the seven pups pelted along, their faces all wearing the intent, fanatical expression I knew so well. When Jock cleared the wall the pups went with him, and when they entered the home stretch I noticed something different. Jock had always kept his eye on the car—his main opponent. Now he was glancing at the pups on either side as though they were the opposition.

There was no doubt that Jock was in trouble. Superbly fit though he was, those stringy bundles of bone and sinew that he had fathered possessed all his speed plus the energy of youth, and it was taking every shred of his power to keep up with them.

Indeed, there was one terrible moment when he stumbled and it seemed that all was lost. But there was a core of steel in Jock. Eyes popping, nostrils dilated, he fought his way through the pack until, by the time I reached the road, he was once more in the lead.

But it had taken its toll. I slowed down before driving away and looked down at Jock standing with lolling tongue and heaving flanks on the grass verge. Everything in his posture betrayed the mounting apprehension that his days of supremacy were numbered. Just round the corner lay the unthinkable ignominy of being left trailing that litter of young upstarts.

I felt for the dog, and on my next visit to the farm about two months later I wasn’t looking forward to witnessing Jock’s final, inevitable degradation. But when I drove into the yard I found the place strangely unpopulated.

“Where are all your dogs?” I asked Robert Corner.

“All gone. There’s a market for good working sheep dogs.”

“But you’ve still got Jock?”

“I couldn’t part with him. He’s over there.”

And so he was, creeping around as of old, pretending he wasn’t watching me. And when I drove away, it was as it used to be, with the little animal running beside the car, but relaxed, enjoying the game, flying effortlessly over the wall and beating the car down to the road with no trouble at all.

I think I was as relieved as he that he was left alone with his supremacy unchallenged; that he was still top dog.

The Venus Incident

One day while I was having tea, Josh Anderson, one of our local barbers, arrived on my front doorstep. He was carrying his light-grey dog, Venus, a hound of baffling lineage that looked like a miniature sheep. She was bubbling saliva from her mouth and pawing frantically at her face.

“She’s choking, Mr Herriot … she’s had a chicken bone.” He was on the verge of tears.

I grabbed the animal’s jaws with finger and thumb and forced them apart. And I saw with a surge of relief a long bone jammed tightly between the back molars and forming a bar across the roof of the mouth.

“You can stop worrying, Mr Anderson, the bone is stuck in her teeth. Come through to the consulting room and I’ll have it out in a jiffy.”

I could see the man relaxing as we walked along the passage to the back of the house. “Oh, thank God for that, Mr Herriot. I thought she’d had it. And we’ve grown very fond of the little thing. I couldn’t bear to lose her.”

My son, Jimmy, age five, had left his tea and sandwiches and trailed after us. He watched with mild interest as I poised the instrument. Even at his age he had seen this sort of thing many times and it wasn’t very exciting. But you never knew what might happen.

Usually it is simply a matter of opening the mouth, clamping the forceps on the bone, and removing it. But Venus recoiled from the gleaming metal, and so did the barber.

I tried to be soothing. “This is nothing, Mr Anderson. I’m not going to hurt her in the least, but you’ll just have to hold her head firmly for a moment.”

Mr Anderson took a deep breath, grasped the dog’s neck, screwed his eyes shut and turned his head as far as he could.

“Now, Venus,” I cooed. “I’m going to make you better.”

Clearly, Venus didn’t believe me. She struggled violently, pawing at my hand, to the accompaniment of strange moaning sounds from her owner. When I did get the forceps into her mouth, she locked her front teeth on the instrument and hung on fiercely. Mr Anderson could stand it no longer and let go.

Venus leaped to the floor and resumed her inner battle while Jimmy watched appreciatively. Things were looking up.

“I tell you what, Mr Anderson. I’ll give her a short-acting anaesthetic.”

Josh’s face paled. “Put her to sleep, you mean?” Anxiety flickered in his eyes. “Will she be all right?”

“Of course. Just leave her to me and come back for her in about an hour.” After he had left, I quickly made up a dose of pentothal.

I scooped Venus from the floor onto the table. Her jaws were still clamped tight and her front feet at the ready.

“Okay, old girl, have it your own way,” I said. I gripped her leg above the elbow and slid the needle into her raised radial vein. Within seconds her head dropped and her body sagged onto the table.

“No trouble now, Jimmy,” I said.

I pushed the teeth apart effortlessly with finger and thumb, gripped the bone with the forceps, and lifted it from the mouth. “That’s the professional way to do it, my boy. No undignified scrambling.”

My son nodded briefly. Things had gone dull again. He had stopped smiling. My own satisfied smile, too, had become a little fixed. I was watching Venus carefully and she wasn’t breathing. I told myself that there was no danger. She had received the correct dose. Just the same, I wished to God she would start breathing.

Jimmy had a feeling that something unpredictable, something funny, was going to happen now. He was right. I lifted Venus from the table, shook her vainly a few times above my head, then set off at full gallop along the passage. I could hear the eager shuffle of my son’s slippers behind me as I made a headlong rush for the lawn.

There I dropped the dog on the grass and fell down on my knees by her side in an attitude of prayer. I waited and watched as my heart hammered, but those ribs were not moving.

This just couldn’t happen! I seized Venus by a hind leg in either hand and began to whirl her round my head, attaining a remarkable speed as I put all my strength into the helicopter-like swing. This method of resuscitation was much in vogue at the time. It certainly met with the full approval of my son. He laughed so hard that he fell down on the grass.

When I stopped and glared at the still-immobile ribs, he cried, “Again, Daddy, again.” Seconds later Daddy was in full action once more with Venus swooping through the air like a bird on the wing.

The performance exceeded all Jimmy’s expectations. He probably had wondered whether it was worth leaving his jam sandwiches to see the old man perform, but how gloriously he had been rewarded. I don’t know how many times I stopped, dropped the inert form on the grass, then recommenced my whirling, but at last the chest wall gave a heave and the eyes blinked.

I dared not get up immediately because the old brick walls of the garden were still spinning around me.

Jimmy was disappointed. “Aren’t you going to do any more, Daddy?”

“No, son, no.” I sat up and dragged Venus to my lap. “It’s all over now.”

By the time Josh Anderson arrived, his pet was looking almost normal. “She’s still unsteady from the anaesthetic,” I said, “but that won’t last long.”

“Did you have any bother with her?”

My parents brought me up to be honest, and the whole story almost bubbled out of me. But why should I worry this sensitive man?

I swallowed. “Not a bit, Mr Anderson. A quite uneventful operation.”

A Border Terrier at Last

I had wanted a border terrier since I first arrived in Yorkshire nearly 50 years ago. But every time I lost one of my own dogs there was never a Border terrier available.

Most recently I had Hector, a Jack Russell terrier, and Dan, a big black dog who had belonged to our son Jimmy, now a veterinary surgeon. When Jimmy married, he left Dan with us. I spent many happy days with both dogs, driving along the roads and lanes of Yorkshire on my veterinary rounds and walking through the countryside during my free time.

After Hector and Dan died within a year of each other, I seemed to be in a state of limbo for several months—the only time in my life that I can remember being without a dog—and my walks would have lost their savour but for the fact that my daughter, Rosie, who lived next door, acquired a beautiful yellow Labrador puppy. She called her Polly, and I found to my delight that I had another companion. But my car seemed very empty as I went on my rounds.

It was a Saturday lunchtime when Rosie came in and said excitedly, “There’s an advertisement in the newspaper about some Border puppies. It’s a Mrs Mason in Bedale.”

I was all for immediate action, but my wife’s response surprised me. “The paper says that these pups are eight weeks old,” Helen said, “so they’d be born around Christmas. Didn’t you say that we’d be better with a spring puppy?”

“That’s right,” I replied. “But, Helen, these are Borders! We might not get another chance for ages!”

She shrugged. “Oh, I’m sure we’ll find one at the right time if only we’re patient.”

“But … but …”

“Lunch will be ready in ten minutes,” Helen said. “You and Rosie can take Polly for a walk.”

As we strolled along, Rosie turned to me. “What a funny thing. Mum is as keen as you to get another dog and yet here is a litter of Borders—the very thing you’ve been waiting for. It seems such a pity to miss them.”

“I don’t think we will miss them,” I murmured. “In fact, I’ll lay a small bet that when we get back, she’ll have changed her mind.”

On our return Helen was talking on the telephone. She turned to me and spoke agitatedly. “I’ve got Mrs Mason on the line now. There’s only one pup left out of the litter and there are people coming to see it. We’ll have to hurry.”

We quickly ate our lunch; then Helen, Rosie, granddaughter Emma and I drove to Bedale. Mrs Mason pointed to a tiny creature under the kitchen table. “That’s him,” she said. I reached down and, as I lifted the puppy, his tail wagged furiously and the pink tongue was busy at my hand. I knew he was ours.

The deal was quickly struck and, as we drove home with the puppy in Emma’s arms, a warm thought came to me: After nearly 50 years I had my Border terrier.

Helen and I settled down happily with Bodie. Helen had a dog to feed again, and I had a companion in my car and on my bedtime walk, even though at the moment he was almost invisible on the end of his lead.

His first meeting with Polly was a tremendous event. Bodie fell in love. This is no exaggeration. Polly became and is to this day the most important living creature in his world. Since she lived next door, Bodie was able to watch her house from our sitting-room window. A wild yapping was always the sign that the adored one had appeared in her garden. Fortunately, for his peace of mind, he had a walk with her every day.

One unfortunate result of Bodie’s infatuation is that he has become insanely jealous. He hurls himself unhesitatingly at any male dog, however large, who might be a possible suitor of Polly’s. Usually Bodie comes off second best. Yet he never surrenders.

Recently I had to stitch up his shoulder after an encounter with an enormous cross-bred Alsatian. By the time I dived in after Bodie’s unwise attack, the dog was waving him around in the air by one leg. But my Border, his mouth full of dog hair, was still looking for more trouble.

When he was about a year old, I was walking down a lane with Polly and Bodie trotting ahead. Suddenly Polly picked up a stick, Bodie seized one end of it, and in a flash a hectic tug-of-war was raging. Bodie growled in fierce concentration and, as Polly glanced at me with amusement in her eyes, I had the uncanny impression that I had got Dan, who loved carrying sticks during our walks, and Hector back again.

Bodie obviously regards himself as a tough guy and, as such, seems a bit embarrassed about showing his affection. If I am sitting on a sofa, he will flop down by my side, as though by accident. And he has a particular habit of creeping unobtrusively between my feet when I am writing. He is down there at this moment.

There aren’t that many Borders around and I find myself staring with the keenest interest whenever I see one. Other owners seem to be fascinated with Bodie’s scruffy charisma. There is a bond among us all.

Last summer, just after I had put my car on the ferry between Oban and the island of Barra in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides, I noticed a silver-haired American gentleman gazing at Bodie stretched out in the back window. The man told me about his own Border.

“Magnificent dogs,” he murmured reverently. He was voicing my own feelings, but when I think of Bodie I am not concerned with the merits of the breed. The thing that warms and fills me with gratitude is that he has completely taken the place of the loved animals that have gone before him.

It is a reaffirmation of the truth that must console all dog owners: that their short lives do not mean unending emptiness; that the void can be filled while the good memories remain.

From James Herriot’s Dog Stories by James Herriot (Pan Macmillan), © 1986 The James Herriot Partnership

Previously published in Reader's Digest November 1986

Illustrations by Elizabeth Traynor