- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Bonus Read

- /

Living Hell

Two years ago massive, out-of-control bushfires were burning across much of Australia. Writer Bronwyn Adcock was among those caught up in the chaos

The Gospers Mountain fire consumed a vast expanse of land north-west of Sydney.

The Gospers Mountain fire consumed a vast expanse of land north-west of Sydney.

One afternoon in late November 2019, I left Canberra in a haze of bushfire smoke to drive back to my home on the South Coast of New South Wales (NSW). As I headed east, past dried-out farm country and stands of brittle eucalypts, a fierce wind whipped up a thick fog of dust and smoke. The smoke could have been coming from anywhere—there were more than 60 fires burning across NSW that week.

About halfway between the national capital and the coast, I pulled over to do a phone interview for a story I was working on about the extraordinary bushfire season already unfolding.It had started unseasonably early in Queensland in late winter, before moving into northern NSW in spring.By early November, more than 1.6 million hectares had been razed, six people were dead and nearly 500 homes were gone in NSW’s north. Places thought to be impervious to fire, such as rainforest and coastal swamps,were burning. At one point, the firefront was 6,000 kilometres long.

All this before the first day of summer. Fire chiefs and scientists warned the worst was still to come. I was starting to frame my story around something I’d read by ProfessorDavid Bowman, an experienced fire ecologist from the University of Tas-mania. He’d predicted this fire season would “reframe our understanding of bushfire in Australia”, and it would be“teaching us what can be true under a climate-changed world”. What would this new world look like, I wondered,and how prepared were we?

The author, Bronwyn Adcock, and her husband Chris.

The author, Bronwyn Adcock, and her husband Chris.

Before I made my phone call, I checked the Fires Near Me app on my phone. This is the NSW Rural Fire Service's platform for distributing bushfire information. Anyone living on a bush property, near state forests or national parks, relies on it.

On my phone, I could see a new fire had appeared on the map. It wasn’t near my home, but it was near the highway. I cancelled the interview and left quickly in case the road was closed.

The fire was in dense bushland, a couple of kilometres from Nelligen, a village about half an hour inland from the tourist town of Batemans Bay, on the coast. Arriving in Nelligen, I could see clouds of smoke pulsing hundreds of metres into the sky. Small spot fires were breaking out closer to town. Car doors were slamming, and people were screeching in and out of driveways as they raced to be wherever they needed to be. Some stood transfixed, talking loudly into phones, eyes locked on the fire. I was struck by a sense of collective fear.

Exactly a week later this fire would be bearing down upon my own property with a ferocity I could never have imagined, and I would be waiting in another town to see if my husband and home had survived.

Over the course of the summer the Currowan fire—named after the state forest where it was ignited by lightning—would continue to threaten my extended family, friends and community. It would take lives and more than 300 homes. It would give us a day when there was no safe place left to be.

STATE OF EMERGENCY

For many Australians, the first real sign that something we weren’t equipped to handle had arrived came during the first week in November. Nearly 100 fires were burning out of control across NSW, and 17of them were considered life-threatening emergencies.

The state’s fire chief predicted that the days ahead would be “the most dangerous bushfire week this nation has ever seen”, and on 11 November,NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian declared a seven-day state of emergency,closing nearly 600 schools.A catastrophic fire warning was issued for the state’s most populated areas, from Newcastle down to Sydney, Wollongong and the South Coast.In a statement, the Rural Fire Service(RFS) warned people that the scale of the danger meant not everyone would get help: “There are simply not enough fire trucks for every house. If you call for help, you may not get it.”

All firefighting agencies were stretched, not just the RFS. There were not enough NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service firefighters or experienced fire managers. And, despite Australia being two and a half months into its worst-ever fire season, only half of the large, high-volume water bombers that Australia leases from the northern hemisphere had arrived.

For its first five days, the Currowan fire burned in the sparsely populated forests that lie just inland from a string of small South Coast villages, such as Bawley Point. My property is on the side of a mountain that marks one of the edges where this vast backcountry ends and the coastal terrain begins. There was no immediate threat, but some days I could see smoke rising behind the mountain, and I started to find the occasional burnt leaf on the lawn.

The Currowan fire cast ominous clouds of smoke and dust over much of the New South Wales South Coast.

The Currowan fire cast ominous clouds of smoke and dust over much of the New South Wales South Coast.

We are always, more or less, ready for fire. When we built a decade ago,we used non-combustible materials and installed huge water tanks. Firehoses are permanently fitted on the house and we maintain a large cleared area around the house. But that week I pulled out the bags of fireproof clothing and bought extra sprinklers. Local RFScrews and firefighters who worked for national parks and state forests traipsed through the bush around the clock,strengthening containment lines or locating the edges of the fire. Volunteers with day jobs or family responsibilities took the night shift.

By the end of its first five days, a Saturday night, the Currowan fire was nearly 8,000 hectares in size and only30 per cent contained. Our best hope was waiting for rain that everyone knew wasn't coming. Another disquieting thing happened that week: the FiresNear Me app stopped working. On the ground it felt as if we were flying blind.

THE FIRE COMES FOR US

Six days after it ignited, the Currowan fire left the back country and started roaring towards the small towns and villages along the coast, as well as hundreds of more isolated properties, including my own. Thick orange smoke churned in the sky. I received a text message from emergency services telling people in our area to seek shelter.

I bundled photo albums and children into the car and drove them to my parents’ house, in a semi-rural farming area about 40 kilometres further north, well away from the fire, then returned home to work with my husband, Chris, on final preparations.A WhatsApp group had sprung up, with people in our area sharing information about the path of the fire. We knew it was coming, but we didn't know exactly where, or when.Our Achilles heel was a place on the mountain we called the ‘saddle’; if it came through the saddle, the terrain would serve as a funnel, and any fire would be catastrophic.

The first night, I was home alone.Chris is an RFS volunteer and was out with a truck. Every few hours I would go outside to look and smell. At 3 a.m.I jolted awake to the lights of a longtruck moving through the forest below us. It was a beekeeper, coming to remove his hives. I remembered a story I'd read about the North Coast fires, of beekeepers coming to check their destroyed hives after a fire went through and being traumatized by hearing animals screaming in pain, and I was struck with a terrible clarity about the situation we were in.

The next afternoon I left, joining my children at my parents’ house. Chris stayed to defend our home. Police roadblocks shut off 50 kilometres of highway; you were either in the fire zone or you were out. We’d discovered a way to listen to the RFS emergency radio scanner—real-time information about the path of the fire—and I had it on constantly.

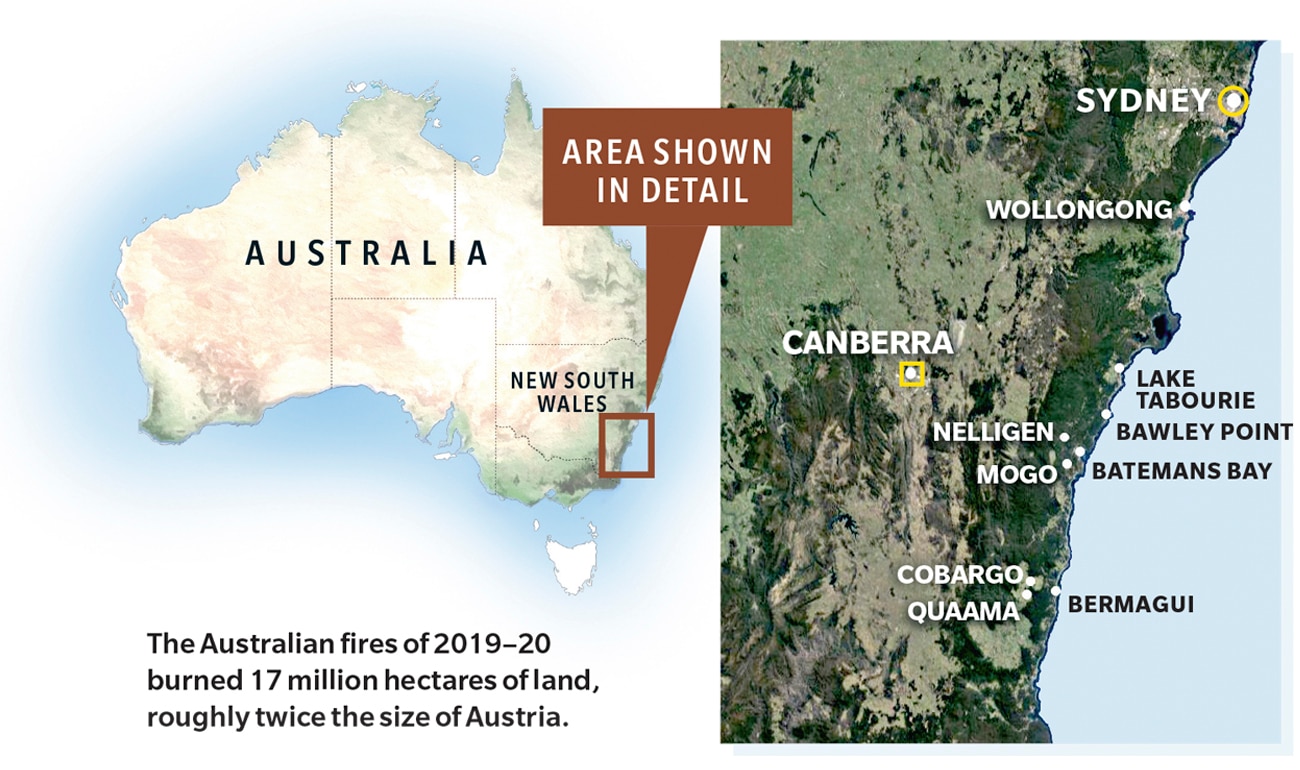

The Australian fires of 2019–20 burned 17 million hectares of land, roughly twice the size of Austria.

The Australian fires of 2019–20 burned 17 million hectares of land, roughly twice the size of Austria.

Tuesday afternoon, exactly a week after Currowan ignited, in a last,strange stab at normality, I found myself sitting in the car at my son’s cricket training, listening to the scanner, madly scribbling down notes. The WhatsApp group was pinging. On a map, I was plotting the emergency calls and reports of fire, and at 6 p.m.I knew with certainty it was coming over the saddle. I called Chris, but he already knew—because the fire was upon him and he was fighting it.

While the fire front was coming from the west, the first flames arrived from the east. The wind had carried burning embers kilometres ahead,igniting the forest below us and sending a canopy fire burning up the hill towards our house. It wrapped around the house and was then joined by the front, coming down the hill from the west.

With the canopies flaming, the fire ignited in the short grass, racing up under the house and licking at its edges. The carport and shed started exploding. Within minutes, the three possible escape routes through the forest to the highway were on fire.

When Chris called about 20 minutes later, I could hardly hear him for the roar and the heave in his voice,but I heard him say he needed help.I yelled ‘get into the house’ and the phone cut out.

I called the mobile number of David Sharpe, Chris’s deputy captain in our local RFS. “We’ll get him,” Sharpe said.

I waited for nearly an hour—a time of terrible, grey limbo when I shut myself in a room at my parents’ house, the children playing outside—until the call came to say Chris was alive.

It was too dangerous to stay and protect our house. When I heard, the next day, that our house was still there,enormous relief was again tempered;three of our neighbours had lost theirs.

The fire burned right up to Bronwyn Adcock’s house, with her husband Chris trapped inside.

The fire burned right up to Bronwyn Adcock’s house, with her husband Chris trapped inside.

We’d had our turn, but the Currowan fire was still launching at several small coastal communities, and dozens of properties around us. Everyday, someone I knew was in danger.Aerial resources had turned up: water bombers hummed in the sky. Still,there were not enough resources to go around for everyone.

The highway remained closed for eight days. With people in the fire zone running low on food, ice and medicine, I gathered things they needed and met Chris at the roadblock. I exchanged the supplies for a forgotten homework book and two guinea pigs.

By that weekend, on Sunday, 8 December, more than half of the 100 fires across NSW were out of control, and we were just one of many communities being upended.The Gospers Mountain fire, which started in Wollemi National Park in October with a lightning strike, was now consuming a vast area north-west of Sydney, including the Blue Mountains, and was being described as a “mega fire”. On social media, the Bureau of Meteorology said: “The massive NSW fires are in some cases just too big to put out at the moment.

”In the second week of December the air quality index in Sydney reached 11 times higher than ‘hazardous’, with buildings being evacuated as smoke triggered fire alarms.

By late December, the Gospers Mountain fire was so voracious it was filmed travelling up the sheer 200-metre cliffs of the Grose Valley in the Blue Mountains. By then it had burned through 4,68,000 hectares, earning the dubious distinction of being the biggest forest fire from a single ignition point in Australian history.

Much of the town of Cobargo was devastated by bushfires on 31 December 2019.

Much of the town of Cobargo was devastated by bushfires on 31 December 2019.

HORROR AT THE COAST

Into late December, the Currowan fire continued to grow in all directions. It merged with another fire on its northern flank. Some days it flared,emergency warnings were issued,alerts sent for ember attacks, then it would subside. Only to have the process repeat days later.

The charred landscape around our property was deathly quiet. I laid out water and feeding stations for the echidnas, wombats and wallabies I once saw every day, and they were left largely untouched. The once forested landscape was stripped so bare I could see contours in the land I never knew were there.

While our home survived, it was uninhabitable because the fire had consumed all our water tanks, the underground septic system and solar power. I’d found a temporary place to live in Bawley Point. It was near our home, and because the fire had already burned right up to the village’s edges, it seemed unlikely to burn again.

I learnt more about the night of the fire at our place. The forest into our property was already well aflame when the Bawley Point RFS crew arrived to rescue Chris. The captain,Charlie Magnuson, directed the crew of one other man and three women to activate sprinklers outside the truck and prepare fire blankets before driving in, past flames on both sides of the road, higher than their vehicle. They risked their own lives. I dwelled on this, not always comfortably, understanding what an enormous thing it was that I had asked of these people.

On the morning of 31 December—New Year’s Eve—I woke at 3 a.m. Ever alert, the first thing I did was check the now-working Fires Near Me app.I couldn’t believe what I was seeing.The day before, a new fire had started in remote bush at a place called Badja State Forest, around200 kilometres south-west of Bawley Point, on the far South Coast. Now,the app was showing it was barrelling towards towns, including Cobargo,a semi-rural community near my brother's farm. I texted him; he was already in the car with his family,racing to the coast.

The Badja Forest Road fire moved so swiftly and ferociously in the hours before dawn that many people only rose from their beds as the fire was upon them.

I turned on the RFS scanner and it was horror and utter chaos. An RFS crew reported that they were pulling children out of a burning home. (“They have no shoes on—can someone get me an ambulance?”)Houses were burning in the village ofQuaama. A truck tried to save them,then suddenly it was: “Red, Red,Red—we are retreating to the fireshed, we are on life protection only.”A plea to stop Cobargo residents fleeing straight into the path of the fire. News that shops in the historic town were on fire. And a desperate voice: “There’s no bloody trucks, so we're buggered.”

By morning, around 5,000 people were sheltering in the little coastal town of Bermagui, including my brother and his family. Sitting in the kitchen at Bawley Point, around breakfast time, I heard a report :“Mate, I think we could be one hour from impact on Bermagui and we have no trucks there.” I thought I was going to vomit. I googled the safest way to shelter from fire in a car,texted instructions to my brother, then walked outside to breathe.

I learnt the Currowan fire was also on the move that morning when Isaw a neighbour, who’d just returned home after being evacuated from her workplace in the town of Batemans Bay, around 40 kilometres south of Brawley Point. She had a small burn on her arm from an ember. I was so shocked I made her repeat the story several times: an ember attack in town?

The Currowan fire was in fact going through parts of Batemans Bay, the village of Mogo, and into two beach-side hamlets packed with holiday-makers. Thousands of people were chased on to beaches, watching as houses went up in flames. Hundreds of properties were burnt.

Phone and internet communications were patchy, but as the day progressed,I started to hear that something terrible was also happening to our north. The Currowan fire had raced into the small lakeside hamlet of Conjola Park—around 40 kilometres from Bawley Point—just before lunch. Some residents say the first they knew of it was when their yard was on fire.

Locals trying to defend their homes say the town water supply stopped working. Fire and Rescue NSW trucks arrived, but without town water they were limited in what they could do. The only road out was blocked by fire, barely passable for even emergency services, so residents and thousands of tourists staying in a caravan park were stuck, some fleeing into the lake—where they then saw in the new year. By the morning, 89 homes were gone and three people in the immediate area of Conjola were dead.

In all, the fires around New Year’s Eve took eight lives on the NSW South Coast. In the Eurobodalla Shire alone,which covers the towns of Batemans Bay and Mogo,more than 450 homes were destroyed—the vast majority by the Currowan fire.

The Currowan fire struck the Kangaroo Valley, south-west of Sydney, in early January. Three men managed to escape after their National Parks truck hit a fallen tree.

The Currowan fire struck the Kangaroo Valley, south-west of Sydney, in early January. Three men managed to escape after their National Parks truck hit a fallen tree.

“YOU HAVE TO CRY”

On the first day of 2020,residents of the South Coast and thousands of tourists woke to no power and virtually no internet or phone communications. Still reeling from the fire front that had just passed through—and which was still burning—we were warned an even more dangerous fire day was coming in four days. Premier Berejiklian again announced a state of emergency, the third for the season, and declared a ‘tourist leave zone’ covering a 14,000-square-kilometre area between Nowra—around 90 kilometres north of Bawley Point—and south to the edge of the Victorian border.

The highway to our south was completely impassable. The only escape route out was north, and for two days this route was rarely safe or open.At times, the gridlock of traffic waiting to escape stretched out for nearly10 kilometres; small convoys would get through, only to have the roadblocked again by fire. Holiday-makers desperate to leave slept in their cars on the roadside.

Petrol stations ran out of fuel, and the few that still had it served queues stretching out of sight. Hordes gathered outside the local grocery store,where only a small number of people were let in at a time.

As shelves emptied, the mayor of the local Shoalhaven council issued a plea: just take what you need.Water supplies and waste systems were damaged, and warnings were issued to some coastal communities to boil drinking water and avoid swimming in the ocean. In a surreal start to 2020, I was rationing fuel and pooling food with friends.

The fires cast an eerie glow over holiday-makers who were forced to huddle on the beaches around Batemans Bay.

The fires cast an eerie glow over holiday-makers who were forced to huddle on the beaches around Batemans Bay.

On the second day of the year,I came home to find Bawley’s RFS captain, Charlie Magnuson, in tears at our kitchen table. It had been along and gruelling fire season, but these few days had been especially tough. The morning Conjola Park went up in flames, the Bawley RF Shad no fire trucks—one was broken down, the other seconded elsewhere.

Eventually they’d borrowed one, with part of the crew being dispatched to Conjola Park—to find a community destroyed, residents wandering the streets in shock, thousands of distressed tourists trapped on the edge of the lake—while the rest raced to a hamlet further north to rescue two people who were suffering horrific burns. The crew gave first aid and comfort to them while they waited for a helicopter. “You have to cry,” Magnuson said. “There’d be something wrong if you didn’t.”

A FINAL BRUSH WITH FIRE

My family had one final brush with the Currowan fire. On January, the tourist convoys had finally escaped the region and the South Coast was as quiet as winter.For a brief moment that morning, as I had my first swim in the ocean for the season, I dared to hope that maybe the forecasts of a terrible fire day had been wrong. But then I walked up the Bawley Point headland and saw new black smoke billowing out to my north, near the little village of Lake Tabourie.

Some people had evacuated from Tabourie earlier in the day as a precaution, but now cars were pouring into Bawley with those making a last-minute escape. I called two people I knew who had remained but were not planning to defend. You need to move now, I said.

I received a phone call from a neighbour telling me that smoke was coming from behind the mountain at our already burnt property.I pulled on fireproof clothing and,with a friend, raced home. The windwas roaring and newly burnt leaves were coming in the air from behind the mountain. With broken tanks and burnt-out pipes, I could barely cobble together a water supply. I quickly lost my nerve for being there.

On my way back to Bawley Point,an RFS bushfire alert pinged on my phone—it was a ‘seek shelter as the fire approaches’ warning for an area that covered from Bawley to as far north as Nowra.

Back in the Bawley house—which was now sheltering 12 adults and children and a few too many dogs—we debated whether to go to the headland straight away or to wait. The power went out.

A strong southerly wind came through. Not long after, I got a phone call from someone I knew to be generally unflappable, but his voice was racing as he started telling me about how he’d just been helping a friend defend a property further north when the southerly had whipped up a firestorm that he had barely escaped in his car.

Just as I was wondering why he was telling me this, he got to his point:“Where are your mum and dad?”My parents’ house—the place where we had first sheltered when the fire hit our property a month earlier—was now apparently in the path of this latest reach of the fire.

I called them immediately. Dad answered just as they were pulling into the local showground to take shelter with around 100 people and countless animals. They’d been at home, with no sign of fire, when everything went black and they heard a pinging on the roof.It was raining embers, and within seconds the yard was on fire. All they had time to do was get in the car and drive away, leaving the lights and TV on.

Billions of animals died in the Australian fires, while many others, including this injured koala at the Port Macquarie Koala Hospital, were rescued.

Billions of animals died in the Australian fires, while many others, including this injured koala at the Port Macquarie Koala Hospital, were rescued.

We discovered the next day their house had been saved by a group of local men who turned up in their utes. They saved numerous houses that day—places the RFS couldna get to. This is the flipside of the story of this bushfire season: Australians doing everything they could.

The 2019–20 Australian bushfire season burned more than 17 million hectares of land—equivalent to 70 percent of the land area of New Zealand.Thirty-three people, including nine firefighters, died and more than 3,000homes were destroyed. More than three billion animals were estimated killed, with the possibility that some endangered species are now extinct.In NSW, a third of the national park estate and more than 80 per cent of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area were burnt. The estimated cost to the economy was in the tens of billions of dollars.

The Monthly (February 2020), Copyright © 2020 by Bronwyn Adcock.