- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Classic Reads

- /

Lion in the Living Room

Five decades after two young men brought a playful cub into their London home, the tale has touched a whole new generation

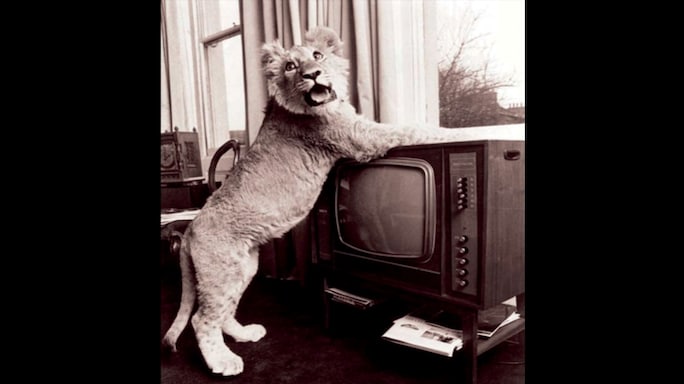

Christian the lion plays in Bourke and Rendall’s London flat in 1970.Photo: Derek Cattani

Christian the lion plays in Bourke and Rendall’s London flat in 1970.Photo: Derek Cattani

The story begins in London in the swinging ’60s. In the exotic-animals section of the legendary department store Harrods, with its motto Omnia Omnibus Ubique—all things for all people, everywhere—a lion cub sits in a small cage.

Two fashionably long-haired, bellbottom-wearing young Australians, John Rendall and Anthony ‘Ace’ Bourke, chance upon the little African cat and decide to buy him. Rendall and Bourke name the cub Christian and raise him as a pet in their groovy pad in the city’s affluent Chelsea area. Their domesticated charge eventually becomes too big for their flat and for London, so they take him to Africa in August 1970.

A remarkable story so far, but it’s what occurred after this which made Christian the lion a 21st-century pop-culture sensation.

A year after parting with their beloved pet, Rendall and Bourke travelled to northern Kenya, where Christian had been successfully assimilated into the wild. Their reunion with the lion was filmed. A few years ago, the moment was posted on YouTube, where it has generated more than a hundred million hits and went viral, becoming a staple for email forwards.

If you haven’t seen it yet, the three-minute clip shows Christian perched on a rock as the two men wait expectantly about 70 metres away. The animal stares at the men, before taking a few steps closer for a better look. Suddenly there is an undeniable flash of recognition and the young lion leaps into action, grunting with excitement as he makes a beeline for the waiting pair and bounds into their open arms. Wrapping his huge paws around their shoulders, the lion fervently licks his old friends’ faces and nuzzles at their necks.

The scene has such emotional power it could be mistaken for a scene from a choreographed Hollywood movie that employs modern animatronics. But this is no fictional tale; rather, it’s an enchanting glimpse into the true story of a lion called Christian.

For many viewers, no doubt, the clip’s appeal may stem from simple amazement over the fact that the wild animal did not attack the men. But its emotional impact on others is something Rendall and Bourke, almost 43 years on, are still trying to understand.

“Is it the depiction of such a close bond between animals and humans? Is it about growing up and separation? Is it about loss and loneliness and the joy of reconnection? Is it the unconditional love Christian demonstrates?” They pose these questions in the introduction of A Lion Called Christian (published by Random House), a revised 2009 book released to fill in the gaps behind the popular video (the book’s original version is from 1971).

Today, Bourke, 66 and Rendall, 68, remain close friends. “Sitting and looking over old photographs, and talking about him, we’ve fallen in love with Christian all over again,” says Rendall, now a committed conservationist who divides his time between London and Sydney, Australia, working as a public relations consultant on travel and wildlife projects.

Bourke lives in Bundeena, on Sydney’s southern outskirts, and has be-come one of Australia’s leading curators specializing in Aboriginal and colonial art. He, too, is involved in “the urgent fight to preserve the world’s wildlife.” There is no doubt their experience with Christian has left an indelible mark. The cub was not born in the wild, but in the now-closed Ilfracombe Zoo in Devon on England’s south coast. Nine weeks later he was sold to Harrods and sent to London by train. At the time, there were no laws restricting the sale of exotic species.

“Animals were traded without limitation and no reliable records were kept,” says Rendall. “Looking back, we should never have been allowed to buy a lion and were unwittingly supporting the trafficking of animals, which we are definitely against. But this was the ’60s.” Things changed in 1973, when UK introduced the Endangered Species Act.

The male cub captivated the two friends, who were both raised in rural areas and had an affinity for animals. In Australia, Bourke grew up with dogs on the edge of the bush, and rescued his first cat at age 11. Rendall was raised on a farm in with kelpies and blue heelers, both Australian breeds of dog.

“Ace and I both had a very strong reaction to the little cub and sat enchanted by the cage for hours,” Rendall recalls. “We were shocked to see this irresistible creature for sale and confined to a small cage, and felt compelled to do something. We decided we must be able to offer something better for the cub.”

Bourke and Rendall were careful about bringing Christian into public spaces, but a ride in an open-top car is too much to resist. Photo: Derek Cattani

Bourke and Rendall were careful about bringing Christian into public spaces, but a ride in an open-top car is too much to resist. Photo: Derek Cattani

It was an impractical idea and a huge commitment for two men in their early 20s, living and working with the owners of an antique-furniture store on London’s trendy King’s Road. They’d left Australia three months earlier with 11 friends from university and travelled through Europe independently before meeting up in London. After a few weeks of careful deliberation and a thorough interview process by Harrods, the friends paid nearly £12 and took the cub home.

“Even though we knew it would only be a short-term commitment of six to nine months at the most, we had to put everything else on hold,” Rendall says.

The large basement level of their aptly named shop Sophistocat was transformed into Christian’s bedroom and play area: toys and special food were purchased, and an arrangement made with a church minister for Christian to have free run of large walled gardens in the neighbourhood for daily exercise.

“It was a terribly exciting, creative time to be in London. There was already a group of Australians, like artist Brett Whitely and writer Germaine Greer, making waves in the art and publishing world. It was a rite of passage and we were all, in our own way, trying to do something different with every opportunity,” says Bourke.

The King’s Road was a Mecca for designers, musicians, artists and creative types, so a resident lion was not out of place. On weekends, the street was transformed into a parade of the flamboyant and the beautiful, and “exotic animals were part of this glamorous mix,” they write in their book.

Rendall and Bourke had no idea what to expect, nor to what degree the cub could be domesticated. Harrods put them in touch with a couple who’d bought a puma the year before, but nothing could adequately prepare them.“We had to wing it in many respects,” laughs Bourke. “There was no one who could give you advice, really. But Christian really was exceptional. He was highly intelligent, had a lovely even-tempered nature and a great sense of humour. He was also incredibly charismatic. People just fell in love with him and it made our job easier.”

Christian quickly settled into a routine, sleeping in his well-equipped quarters and being fed four meals a day according to a carefully balanced diet sheet. The first and last meals were a concoction of baby foods and vitamins, with two main meals of meat during the day. On occasion Christian gratefully gobbled up fillet steak treats from a local French chef who had a soft spot for the lion.

Sophistocat was a “jungle of furniture” and Christian loved a game of cat-and-mouse with his owners. “He was inexhaustibly playful,” Bourke recalls. “He would come up in the evenings and create these games, positioning himself behind pieces of furniture, insisting we ‘hide’ and then stalk us all around the shop. He also loved wastepaper baskets, the friends write in the book, “first to be worn on the head, totally obscuring his vision, and then ripped apart.”

Unlike many other cat family members, lions are social creatures that prefer to live in an extended family pack characterized by affection and intimacy. “We were Christian’s pride,” explains Rendall. “He automatically took us into his orbit, and accepted and loved us as if we were his family.”

Christian quickly became a popular fixture in the neighbourhood. He had a steady stream of admirers stopping by for a game, a cuddle or to observe him from a distance as the ever-growing cub lounged on an antique table in the shop window. “Late in the afternoon he loved to sit in the window, watching the passing activity. He was the area’s star attraction and locals were fiercely proud of him,” they write. “One actress friend of ours, Unity Bevis-Jones, became particularly attached to Christian, stopping by every afternoon to play with him,” says Rendall. “They were mutually besotted.”

Photos of Christian being driven around in a car and eating out at trendy restaurants reflect his celebrity status—he would receive movie premiere invitations and a starring role in a modelling shoot for nightgowns in Vanity Fair. “He was even interviewed by [legendary BBC radio presenter] Jack de Manio,” laughs Bourke.

Nevertheless, his owners were protective and rarely took him outside Sophistocat or the church grounds. “He liked outings, but they were infrequent. We had to ensure Christian’s and everyone else’s safety, so we were cautious,” Bourke continues. Rendall nods vigorously in agreement. “We had to always stay one step ahead and pre-think every situation. Are there windows? Are there open doors? Are there going to be children or dogs?” Fortunately, nothing un-toward ever happened, and Rendall and Bourke were at pains to make sure Christian knew who was boss.

One year after they left him with George Adamson in Kenya, Christian greeted his former owners with great excitement.

One year after they left him with George Adamson in Kenya, Christian greeted his former owners with great excitement.

“He very quickly grew too big for us, but we never let him know,” says Bourke. “We simply ignored any overt demonstrations of his superior strength. If we had put him in a situation where he was unhappy and felt the need to turn on us, we would not have been able to control him because of his size and strength, and the sharpness of his teeth and claws. But thankfully, that kind of situation never arose.”

From the outset, Bourke and Rendall were aware that the environment they’d created for Christian at Sophistocat was a temporary solution. As he grew from 15 kilos to 85, so too did their concerns about his future. Then, by sheer coincidence, the two lead actors of the 1966 hit wildlife film Born Free, Bill Travers and Virginia McKenna, came into the shop to browse for furniture. “They fell immediately under Christian’s spell and wanted to help. They subsequently contacted their great friend George Adamson, one of the world’s foremost lion experts, who agreed to take on the challenge of introducing Christian to the wilds of Africa.”

Together with the animal star of Born Free, a tame lion called Boy, Christian would form the nucleus of a new man-made pride. Travers and McKenna produced documentaries on animal conservation and, to cover expenses, proposed the filming of The Lion at World’s End to follow Christian’s training and journey to Africa.

“It was the perfect solution. We were so thrilled and relieved,” says Bourke. “George warned us a King’s Road lion may have trouble assimilating, but we grabbed at the opportunity with both hands.” In 1970, after lengthy negotiations with the Kenyan government, the two Australians flew to Nairobi with one-year-old Christian. The pair watched on in Adamson’s shadow as Christian instinctively removed thorns from his tender paws during his first walk on African soil and valiantly attempted to stalk his first prey. Curiously, of all the lions under Adamson’s care, Christian made the transition with the greatest ease.

“Apart from initial toughening up, he required no training,” wrote the late Adamson in the 1971 edition of A Lion Called Christian. “No one knew lions better than George did,” says Bourke. “He had an extraordinary understanding and love for them. So although it was difficult to say goodbye, this was the outcome we all wanted. We still can’t believe it all worked out so beautifully.”

Over the course of the next year they kept abreast of Christian’s progress and in 1971 returned to the reserve. Adamson had advised the pair that Christian was likely to remember them, something that is often misquoted in media articles and YouTube’s opening commentary, but even Adamson was surprised by the extreme tenderness of Christian’s greeting.

“The questions everyone asks us after watching the video are: ‘Weren’t you worried?’ ‘Weren’t you scared?’ ‘Didn’t you think he was going to attack you?’” says Rendall. “The truth is, we were absolutely not afraid and never doubted for a second that he’d be happy to see us and it would be a wonderful greeting. We recognized his body language, his loving expression and we knew he was excited. He was bigger, but he was still the same lion we had known intimately for a year, and it was as simple as that.”

When you watch the video, continues Rendall, “you see him looking as if he’s thinking, Is it them? Is it them? We couldn’t bear to wait a minute longer, so we called out to him. And there’s that priceless moment when you can see that he knows, and down he comes.”

Rendall is barely able to hold back the tears as he reminisces about the excitement of that day—Christian looking so healthy, the head of his new pride, showing his old affection. “It encapsulated our friendship, our love for him and his love for us. It was the culmination of all the time and love we put into him.”

In 1972, Rendall and Bourke had one final reunion with the lion who was now fully integrated into the wild. At that time, Christian was about 230 kilos and one of the largest lions Adamson had ever seen. A letter Bourke wrote to his parents at the time reads: “We saw Christian every morning and evening for a walk and a chat. He is much calmer and more self-assured than last year, and stunning to be with. Just as silly. Huge. Jumped up on me only once as before on his hind legs and did it extremely gently. He licked my face as he towered over me. He nearly crushed John trying to sit on his lap!”

Christian’s first night in the African bush was spent with a comfortable pillow and a reassuring paw on Rendall’s face.

Christian’s first night in the African bush was spent with a comfortable pillow and a reassuring paw on Rendall’s face.

They spent nine full days with their former King’s Road pet and were introduced to his pride of lionesses before Christian disappeared into the wilderness, never to be seen by the friends again. Today, Christian has his own Wikipedia entry, Facebook page and a lasting legacy through the work of the George Adamson Wildlife Preservation Trust. The friends marvel at what could be achieved if everyone touched by Christian’s story worked together to address some of the world’s most urgent social and environmental issues. According to Rendall, education is one of the most important pillars of the George Adamson Trust.

“The tragedy of Africa at the moment is that so many educated people are leaving. And many of those left behind are dying of cholera. If you are dying, you are not going to be concerned about wildlife. And if you are starving, the animals become much-needed food to survive. And who are we to say what people can or can’t do to survive?” The revival of interest in Christian’s story, Bourke says, has highlighted how dependent people become on their pets in these stressful times. “We form such close relationships with them. I think that’s one of the main lessons to come from all this.”

YouTube visitors all post their heartfelt responses and repeatedly echo the same sentiment: “Thank you for showing the world that all wild animals deserve to be treated with love and respect. You are an inspiration.”

Editor’s Note: Rendall passed away on 20 January 2022. Yet, their bond continues to inspire awe among millions. Google ‘Christian the lion video,’ to view Ace and Rendall’s reunion with the lion, a year after he was released into the wild.

First published in Reader's Digest May 2009