- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Personalities

- /

From Rolihlahla To Nelson To Madiba: Tracing The Political Life Of Mandela In 10 Points

On the 102nd birth anniversary of Madiba, Reader’s Digest looks at the political journey of South Africa’s first black president

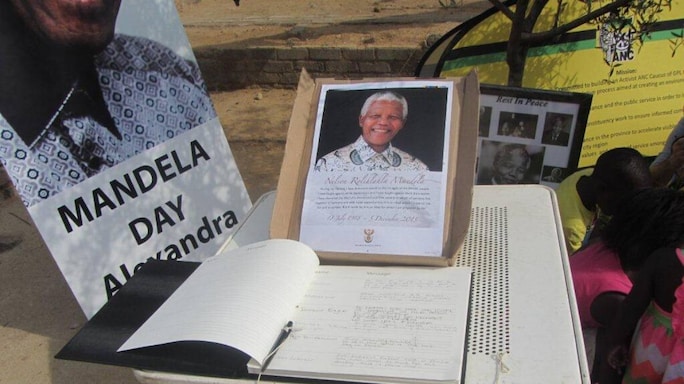

The community of Alexandra mourns the death of Nelson Mandela in 2013. (Photo: Flickr)

The community of Alexandra mourns the death of Nelson Mandela in 2013. (Photo: Flickr)

The year was 1994. South Africa had conducted its first all-race national elections and chosen a coalition government led by Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela—the first black president in the country’s history. Legislated apartheid was now over, and the man who brought his tormented country out of the darkness of government-sanctioned racial segregation into democracy was now resolutely placed as a worldwide symbol of peace and racial equality.

Here is a look at Mandela’s journey to becoming the father of the nation and a global exemplar.

1. Mandela was born to Nonqaphi Nosekeni and Nkosi Mphakanyiswa Gadla Mandela, on 18 July 1918. His parents named him Rolihlahla—the literal translation of which is ‘pulling the branch of a tree’, but colloquially means ‘troublemaker’, in Xhosa. He got the name Nelson when he was 9 years old from a teacher at the Methodist school in Qunu, South Africa. This was in 1920s South Africa—still a British colony—where it was common practice to give African children English names, so that British colonists would be able to pronounce them easier. In his later public years, Mandela was addressed as Madiba—his Thembu-clan name—out of reverence and endearment.

2. After Mandela’s father passed away, 12-year-old Mandela was made a ward of Jongintaba Dalindyebo, the-then regent of the Thembu people, at the Great Place in Mqhekezweni. When Mandela returned to the Place without finishing his BA degree at Fort Hare—he was expelled from the institution for participating in a student protest—the king was furious and threatened to marry him off, unless he returned to finish his degree. Mandela ran away to Johannesburg and worked as a security officer at a mine, till he met an attorney by the name of Lazer Sidelsky, who allowed Mandela to do his articleship through his firm—Witkin, Eidelman and Sidelsky.

3. Though Mandela, along with his African National Congress (ANC) colleague, Oliver Tambo, established the first-ever black law firm, it took him nearly 50 years to get his law degree. Mandela had renounced his claim to the chieftainship of the Madiba clan of the Xhosa-speaking Tembu tribe, with dreams of becoming a lawyer but by Mandela’s own admission, he was a poor student. He enrolled at the University of the Witwatersrand for an LLB, only to quit in 1952. He picked up the study of law again after his imprisonment in 1962 through the University of London, but did not complete that degree either. Mandela finally earned his LLB degree in 1989, in the last months of his imprisonment, through the University of South Africa. Till then, Mandela was only able to practise law because he had obtained a diploma in 1952.

A young Nelson Mandela, circa 1937 (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

A young Nelson Mandela, circa 1937 (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

4. A politically active Mandela joined the ANC in 1944 and became one of the driving forces in the formation of the ANC Youth League (ANCYL). Four years later, South Africa’s first National Party government was elected through a white-only ballot, an event that codified apartheid—and the existing racial segregation already entrenched in the social and economic order—into law. Through laws such as The Race Classification Act, The Mixed Marriages Act and The Group Areas Act, race became the sole marker—and the darker one’s skin was, the more draconian the discrimination.

5. It was against this backdrop that Mandela toured the African nation organizing campaigns of mass civil disobedience. In 1952, Mandela was charged under the Suppression of Communism Act, receiving a suspended prison sentence and a 6-month-ban—a punishment that meant a person could not be quoted, could not travel, speak or write publicly and could only associate with one person at a time.

6. The Sharpeville massacre in March 1960 where police opened fire at a crowd of black protestors sparked a key change in Mandela’s non-violent approach to politics. Around 250 protestors were killed or wounded. Emergency was declared in the country and over 11,000 people, including Mandela, were detained. The ANC was outlawed and designated a terrorist organization. Mandela was therefore technically on the US terror watch list till 2008.

A painting showing the victims of the Sharpeville massacre on 21 March, 1960 (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

A painting showing the victims of the Sharpeville massacre on 21 March, 1960 (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

7. The massacre propelled Mandela to argue in favour of a military wing within the ANC, and the Umkhonto we Sizwe or ‘Spear of the Nation’ was formed. He underwent military training in Ethiopia and became its first commander. When apartheid was eventually dismantled in South Africa, he choose Sharpeville as the site to sign the country’s new constitution on 10 December 1996.

8. After going underground, Mandela is known to have disguised himself as a chauffeur, a gardener and a chef in order to travel in secret. His ability to move around undetected even earned him the nickname ‘the black Pimpernel’, a reference to the novel The Scarlet Pimpernel, about a hero with a secret identity. Despite his undercover skills, Mandela was captured on 5 August 1962 at a roadblock in Natal and sentenced to five years in prison. In the infamous Rivonia Trial that took place in October 1963, Mandela along with several others were tried for sabotage, treason and violent conspiracy. It was during this trial that he gave his famous ‘Speech from the Dock’, on 20 April 1964.

9. Narrowly escaping the death penalty, Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment and spent 27 years in prison, including 18 years on the notoriously brutal Robben Island penitentiary. Forced to perform hard labour in a lime quarry, he sustained permanent damage to his eyesight, and contracted tuberculosis. Increased uprisings led to more political detainees being sent to the prison where they met Mandela and formed alliances that revived ANC networks. Soon, the prison came to be known as the Nelson Mandela University.

Former South African President F. W. de Klerk with Nelson Mandela at the World Economic Forum, 1992 (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Former South African President F. W. de Klerk with Nelson Mandela at the World Economic Forum, 1992 (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

10. During his imprisonment, Mandela refused three conditional offers of release. Major changes in the world resulted in increased national and international pressure to end apartheid and release Mandela.On 11 February 1990, Nelson Mandela was freed from prison by then South Africa President F. W. de Klerk. Together they worked to abolish apartheid laws, free civil-rights protesters, remove bans on political parties and, as a result, prevented civil war. They were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 for their work towards building a rainbow nation.