- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Classic Reads

- /

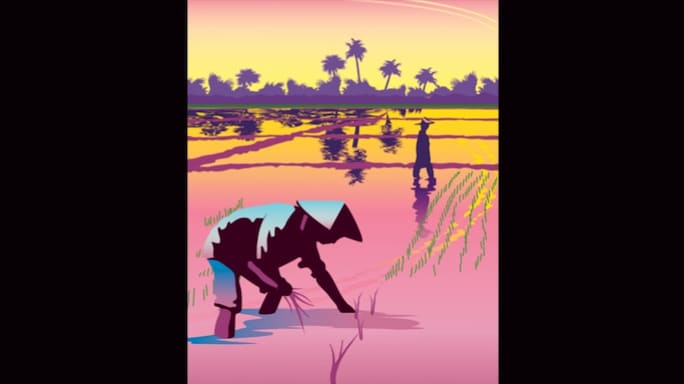

Crawling in the Paddy Fields

Hard physical work taught me an unforgettable lesson: you reap what you sow

illustration: Getty images

illustration: Getty images

I have ploughed, planted, cut harvests, pickled tea leaves and chopped wood in the isolated but beautiful countryside of Kuanhsi in Taiwan. But of all the chores that are a farmer’s lot here, crawling in a paddy field to rid it of weeds is, in my experience, the task that trains one best to develop a Spartan spirit.

Nowadays, of course, the farmer need only use chemicals to kill weeds. It was not so when I was a boy some three decades ago. From the age of eight or so, I had to contribute my share of labour along with my father and two elder brothers, Yuh-hsien and Yuh-tang.

Our family was too poor to afford paid labourers. Kneeling in a paddy field with a hat, a shirt and a pair of shorts my only protection, I was up to my thighs in mud. It splashed all over me, wet, sticky and dirty. When mud splashed into my eyes and on to my lip, I’d stand up, find the kettle of fresh water and try to wash it away; but it was always a long struggle before I could get it completely out of my eyes and off my lips.

The first weeding of the year occurred just before spring, and the second in midsummer. Then the blistering sun beat upon my arched back, making me feel like hot bread stuck to the side of a pan. The evaporating water from the paddy field steamed up my nostrils and face.

Between 10 in the morning and four or five in the afternoon, when the air hardly stirred, perspiration ran in rivulets, making streaks on my mud-covered arms and legs. It felt as if little bugs were crawling all over me. If a drop of sweat ran into the eyes, it would trigger tears. To prevent the sweat from running into my eyes, I kept my face as low as possible.

I told myself, Be patient! What good does it do to begrudge my lot? If my parents and brothers could go on taking it, so I could I. A kind of pride took place of the hurt in me. So thinking, I slowly pulled myself together and I crawled on.

When I pulled out rotten plants, they had a raw stench. The mud was so slimy that it made my flesh creep. Standing up, ploughing or planting, you didn’t feel it so much, but it hit you hard when you were working with your face close to the water.

My skin often developed rashes and my knees bled. The bamboo stakes and the bugs, worms and snakes in the water cut and stung. Moreover, the small leeches sucked blood and caused infection.

On the way home every day, I’d soak myself in the creek and then take a hot bath at home. I could not sit down and eat dinner until I was sure that every bit of dirt had been removed from my pores, and no hint of smell remained. When I put on clean, coarse cotton clothes, fragrant from drying in the sun, it was pure ecstasy.

Once, during my summer holidays, Father was sick, but he worked in the field just the same, because there was so much to do. As I looked at his lean figure, crawling ahead of me, I thought of my own dim future. I was tied to the land by job after back-breaking job, unlike other boys who had freedom to pursue happiness. Why were there people in the world who would never know what it was like to toil, and others, like me, who had been toiling ever since they were small boys, season after season, year after year? Why were some people sitting before electric fans or in air-conditioned rooms, while I was panting and sweating under the blazing sun? Why was there mud and more mud in front of me?

Only we farmers were willing to crawl, to assume the lowliest of positions in order to have a better harvest. Even a buffalo or a horse, when working for man, stands tall. I was suddenly consumed with great pity and great respect for the multitudes of poor farmers, and the focus of my attention began to extend beyond myself and my family. This was an important turning point in my life.

While resting beside a field one day, my brothers and I resolved to pursue useful knowledge and technology to help ourselves and other farmers improve our circumstances, and lighten our burden of labour. This resolve gave me strength so that when I went to university, and later to the US on a scholarship, my spirit rose above personal hardships. Crawling in the mud had taught me to take bleeding and sweating as part of my life, and not to be afraid in the face of difficulties and setbacks. But what was more important was that I had learnt the meaning of ‘you reap what you sow’.

Mother used to say, “Judge a man not by his face, but by his fields.” I appreciate more and more the meaning of these words. The land is dependable, as long as you are willing to toil on it. When the wind blew and the green rice plants swayed like waves in a sea, dazzlingly beautiful, a deep sense of satisfaction swelled up in me.

I laboured hard in the simple, isolated countryside of my home, and I am proud of this. Although later I went into academic research, I shall always remember what working in the paddy fields taught me: plant your feet firmly on the ground, work hard and you will be rewarded.

Editor's Note: The author’s brothers also found work away from the paddy fields. Yuh-Hsien became an agricultural and forestry official. Yuh-Tang became a deputy police superintendent.

From Reader's Digest May 1985