- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Personalities

- /

Another Strange And Sublime Address

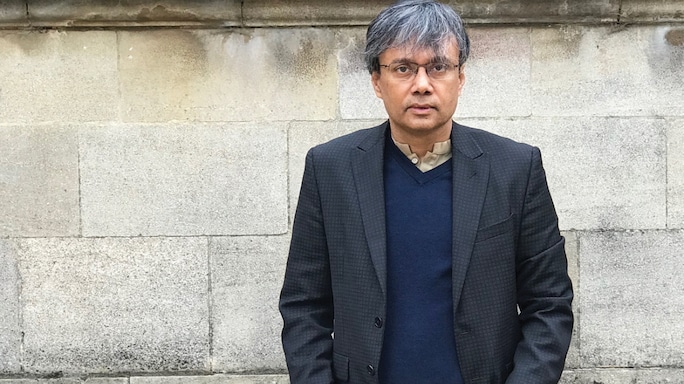

Author Amit Chaudhuri speaks to Reader’s Digest about his latest book, history, music and his attitude towards the teaching of creative writing.

In Sojourn, Amit Chaudhuri’s latest novel, an Indian academic arrives in Berlin as a visiting professor. With time, he merges with the city, loses his sense of self, flits between the past and present, creating a haunting reading experience. The author speaks to Reader’s Digest about his book, history, music and his attitude towards the teaching of creative writing.

Do cities like Berlin, where history weighs heavily, lead to disorientation, as felt by Sojourn’s protagonist?

The state of absorption is what is of primary value and importance to me. What I was playing with was the idea that the narrator goes to Berlin and becomes absorbed in a lot of what he’s seeing. The absorption causes a kind of wavering in the distinctions he would ordinarily—among them, between being an Indian and being a European. So, absorption becomes a form of surrender. [In] those unlikely moments, where he is recognizing places, as if he belonged there … he begins to become so much part of [Berlin’s] history, which he has forgotten, that he begins to lose himself. He begins to lose that sense of who he is.

But how important was the city of Berlin to the story of Sojourn?

I’ve written about cities all my life. I am now investigating [in this novel] a paradoxical history, which is not sufficiently defined by the historical definitions we are conscious of, and by which we define ourselves. Those have to be put aside in such an encounter. So, it’s not a question about thinking about Berlin first or my character first: I’m looking at a moment of historical change that’s long been present for me. I began to write A Strange and Sublime Address in 1986, and by then I would have sensed that a particular world, the world of modernity, was already passing. By the time the book was published in 1991, we had emerged into this new world, the Berlin Wall had just fallen and economic deregulation had taken place. So, this is a kind of moment in which to recollect what happened to us, to me, through this story about the city.

You write that “when freedom is the only reality, you are no longer free”. So, when are you really free?

One is only free in those secret moments of escape, of incompleteness, of failure. When everything becomes homogenized as free, everything is perfected in a sense, and then one is no longer free. If one has no escape from what somebody proclaims to be freedom, then freedom becomes a form of madness. Anything which has no alternative to it, no escape from it, is a kind of oppressive psychological condition. Freedom always consists of alternatives within a system. The system itself cannot be free. There always have to be moments of fissures and breakdowns in the system, from which freedom arises. Once pleasures and alternatives are taken away, one is no longer free, even if the system calls it freedom.

You’ve said that you have an aversion to completeness and perfectness. So does that mean you have a fondness for incompleteness or imperfectness?

I prefer incompleteness and unfinishedness. One of the traditions of cherishing incompleteness is the kind of worldview that, in the arts, we call modernism. In modernism, the ambitions of the European Renaissance—to produce finished objects and also reproductions of finished objects, or in paintings to create the illusion that it’s giving us reality—were rejected in favour of giving us more imperfect, unfinished portrayals in which the process is not kept out of view. We see it also in some in some branches of romanticism, in paintings and in poetry—the love of, say, ruins. It reveals that life lies in the process, the process of making or the process of decay. The process of decay is very akin to the process of making, in that it’s not finished yet. Tagore (who contrasts srishti or ‘creation’ with nirman or ‘construction’ in the 1880s), and, later, Lawrence and Tanizaki speak about this with activity. The finished object, for me, is a kind of dead object.

As a creative writing teacher, what do you teach your students?

I share with them whatever thoughts I might have about this problem we call writing … I do not censor them. The focus of creating writing workshops has taken attention away from the fact that ideas of craft, ideas of writing are all first historically contingent and they arise at a certain point of time, in a particular manifestation, as embodiments of the way we think of writing at any point of time. So, there are no universals when it comes to ‘craft’, for instance. There is no universal rule about overwriting or precision or what a wrong or unnecessary adjective is. This leads us to a great conundrum, and to the mysteries of writing, which we must confront at some point as writers, and teachers of writing.

We also need to look beyond this idea of producing a work which reads well and is publishable. We need to look at questions to do with writing that underlie our decisions—what we take pleasure in, what we don’t take pleasure in, our differences with other writers.

Lastly, because creative writing workshops have become a service industry all over the world, we believe that the centre of our attention is what is happening in the workshop—the writing done by others in the workshop, and primarily the writing that has been done by me, the workshop participant. But we actually pursue writing because we are interested in writing—not just our own writing, but writing itself. And literature as a discipline, criticism as a discipline, was to a great extent formed by writers. That is because the matter of writing was a life-and-death matter to them. Not their own writing, but writing. There is an amnesia about this now.

You are an accomplished Hindustani classical singer. Which do you most identify with—writer or musician?

Music imposes a sort of continuity and routine. One is consciously tied to that particular routine of being a musician, of trying to keep up with its demands, which, for me, has been a matter of more than 40 years. I’ve compared it to sports, but unlike sports, it’s a lifelong activity. As for that question of which one I identify myself with … I will say neither. Of course, I feel anxiety about what I write, and what I publish, and writing also involves pride and self-knowledge. Without that self-belief, I wouldn’t be doing what I was doing. But, there is no self-conscious identity in me as a writer or musician. I just happen to be doing these things.

You have often spoken about the fallacy of the West as a beacon of freedom and liberal thought and secularism. Could you please elaborate?

I think ‘the West’ is a bogus term. I think ‘White’ is a bogus term. What is this extraordinary identity created by a misreading of skin pigmentation? These are such bogus categories because they have no real history, and they allow us to continue to think lazily about history. ‘The West’ as a category made a huge comeback after 9/11, and after globalization. 9/11 legitimized the rise of the West, and it’s a blithe, self-referential term for a club that certain people belong to. Its not a question of being European—you can be Western only as long as you are part of Western Europe or the USA, but not Russia or Poland.

So, it’s a numinous value, quasi-mystical and transcendental. And as a category, it is an insult to secular histories of other parts of the world, which are far stronger and more complex and robust than this version of secularism (which becomes synonymous with something called ‘Western values’) we see now.