- HOME

- /

- Features

- /

- Classic Reads

- /

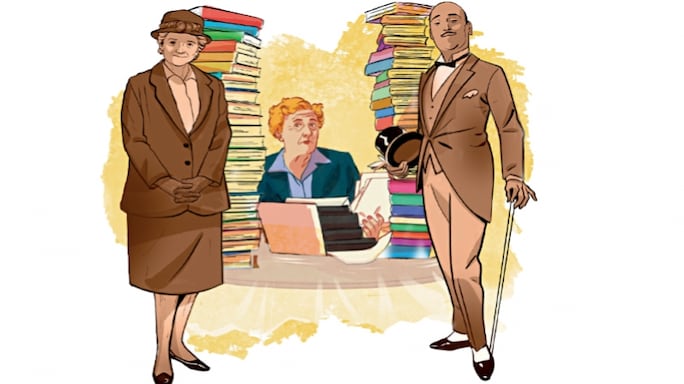

Agatha Christie: Murder by the Book

More widely read than any other English writer, she baffled the world with masterly tales of murder and remained something of a mystery herself

Illustration: Siddhant jumde

Illustration: Siddhant jumde

Last October, connoisseurs of detective fiction eagerly turned the pages of a new novel with special and apprehensive interest. Not only was it the final Agatha Christie book to be published—a mystery entitled Sleeping Murder—there were rumours that in it, the inquisitive Miss Marple, one of the best loved super sleuths ever created, would meet her match and die.

Happily, as critics noted with relief, this particular Agatha Christie trail—like so many others, ingeniously woven into her plot—proved false. The author who in Curtain, hadn’t hesitated to kill off her similarly renowned detective, Hercule Poirot, allowed Miss Marple to surmount all perils, alive and triumphant.

The Times critic, H. R. F. Keating, gladly recorded Miss Marple’s survival and enthused: “It’s vintage Christie, marvellously easy reading, constantly intriguing. How does she do it? Timing. Unerring timing.”

But Agatha Christie remained modest about her achievements. She even played down her prodigious output, once calling herself “a sausage machine”.

By the time of her death, a year ago, last January, at the age of 85, the high priestess of detective fiction had 110 titles to her credit—66 of them full-length murder mysteries—with estimated sales of more than 350 million copies. She has been translated into 157 languages, 63 more than Shakespeare.

Christie wrote her first book in 1920, and made only £25 off it. Photo: Alamy

Christie wrote her first book in 1920, and made only £25 off it. Photo: Alamy

Her stories have inspired 15 films, and 17 of her plays have been staged. The Mousetrap is the world’s longest running play, having opened in London 24 years ago; it is still going strong. Curtain was heading bestseller lists on both sides of the Atlantic the week she died.

In all, Agatha Christie earned an estimated Rs 15 crore from her detective stories. She reputedly made more money than any writer in the English language. She may well have made more money than any writer in history. Before Sleeping Murder was published, the American paperback rights were sold for an unprecedented Rs 75 lakhs.

Born Agatha Miller in Torquay, Devon, she grew up in a well-to-do home with an American father and an English mother who took the unconventional view that schooling was hard on a child’s eyes and brain. Her parents tutored her, and she read a lot, especially romantic novels, and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes—an influence on her subsequent writings, as she freely admitted. One day, when she was ill, her mother suggested that she while away the time by trying to write a short story. That started her on a series of tales of “unrelieved gloom, in which most of the characters died.”

Murder is Announced

In 1915, during the First World War, her eldest sister bet her that she couldn’t write “a good detective story.” She accepted the challenge. By then, Agatha was married to Archibald Christie, a Royal Flying Corps officer, and working as a Red Cross volunteer in a Torquay hospital. Belgian refugees were billeted around town, and from observing them, she evolved the prototype of Hercule Poirot, with his egg-shaped head, waxed moustache and shiny patent shoes. He came up with a solution in Dame Agatha’s first detective novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles.

For three years, The Mysterious Affair at Styles was turned down by one publisher after another. Finally, it appeared in 1920, sold fewer than 2,500 copies and earned her £25. It was not until her seventh book, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, was published in 1926, that Agatha Christie became famous. At the time, she and her husband and daughter, Roseland, were living in Berkshire. Not long after, her comfortable life started coming apart. Her mother died, and her husband fell in love with another woman.

Agatha simply vanished. Her abandoned car was found in a local country lane, and for 10 days, thousands of policemen and volunteers combed the nation for her. Following a telephone tip, the police found her in a hotel at Harrogate, registered inexplicably under the name of the woman her husband was later to marry. The story made headlines, and some cynics called it a publicity stunt to plug The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.

Although it was confirmed that she had been suffering from amnesia, Agatha Christie remained uptight about her disappearance for the rest of her life. However, it had made her name known throughout the land. The book eventually sold more than a million copies.

Two years later, she divorced Colonel Christie, but kept his name for her crime stories. In 1930, she married Max Mallowan, an eminent archaeologist who was knighted in 1968. For years, she accompanied him on digs in the Middle East, helping him photograph and tabulate artefacts. In a book written under the name Agatha Christie Mallowan, Come Tell Me How You Live, she gave a light-hearted account of their expeditions. She also wrote short stories in a book of verse, and under the name of Mary Westmacott, was author of several romantic novels.

Many of Agatha Christie’s stories were first published in The Strand Magazine, such as this one from February 1936. Photo Alamy

Many of Agatha Christie’s stories were first published in The Strand Magazine, such as this one from February 1936. Photo Alamy

Appointment with Death

But it is as a purveyor of the fine art of murder for relaxation that Agatha Christie made her mark. Her books were painstakingly researched. Her hospital work gave her first-hand knowledge of poisons. Her husband’s archaeological expeditions provided occasional background material (Murder in Mesopotamia, Death on the Nile) and she even set one story—Death Comes as the End—in Egypt in 2000 BC, doing “endless research on everyday details.”

One skeptical reader took the Orient Express across Europe just to be sure that Agatha Christie was right about the train switches in Murder on the Orient Express. She was.

The tightly constructed Christie plot—some were thought out while she was in the bath, munching apples; others when she was washing up or cooking—earned her the title ‘Queen of the Maze’. She loved to bamboozle, but maintained that she never actually misled the reader; she allowed the reader to mislead himself.

For example, a murder suspect is asked to verify a date. He crosses the room and squints at a calendar. The reader is misled into thinking the date he tells us is relevant, but the clue is that the suspect is too short-sighted to see across the room.

Another Christie gimmick is the over-the-shoulder ploy. Someone looks straight ahead over another person’s shoulder and is stunned by what he sees. The scene is described to us in detail, so we know exactly what people and things are in the line of vision. The tell-tale clue is tossed off so casually that we fumble it in a series of red herrings.

In one of her most ingenious plots, Dame Agatha made one of the victims the murderer. Another time, she made her detective a killer. Such masterly sleight of hand won her royal approval. When the BBC asked the late Queen Mary what she wanted for a birthday programme, she requested a radio play by Agatha Christie. The author obliged, then rewrote it as a short story and finally a full-length play. She called it The Mousetrap, from the “play within a play” in Hamlet.

The Midas Touch

Dame Agatha never dreamt the play would be so successful, but the royalties which she turned over to her grandson have made him wealthy. In fact, she gave away the rights to many other works while she was still alive, thereby avoiding omnivorous death duties and keeping her estate down to about Rs 15 lakhs when she died.

In later life, she said she wrote only one book a year, delivered to her publisher in time to assure the public ‘a Christie for Christmas’, because if she wrote more, the greater part of the profits would have gone to the government to be spent “mostly on idiotic things.”

St. Martin’s Theatre has been home to Christie’s The Mousetrap since 1974 till date—making it the longest running play in the world. Photo: Alamy

St. Martin’s Theatre has been home to Christie’s The Mousetrap since 1974 till date—making it the longest running play in the world. Photo: Alamy

A shy, retiring woman who loved her garden, Dame Agatha, was described by her literary agent as “an old-fashioned gentlewoman.” She moved, as did her murderers, in a world of large country houses where people dress for dinner and lament the passing of good servants, where the silver is highly polished (to show fingerprints), and where young girls never walk but “run lightly” across the lawn, which is well-manicured (to show footprints).

There are no four-letter words, no Freudian implications, since sex is confined to a chaste kiss. “I don’t like messy deaths. I don’t like violence,” Dame Agatha insisted. Although it was said that she profited more from murder than any woman since the Lucrezia Borgia. “I know nothing about pistols and revolvers, which is why I usually kill my characters off with a blunt instrument—or better still, poisons.”

Since she despised characters who “go around slugging each other just for the sake of it,” she made the dapper little Hercule Poirot rely on “the little grey cells” of his mind to solve his cases. Poirot—fussy to a fault, supremely sure of himself, constantly flicking minute specks of dust off his sleeve and punctuating his sentences with bits of schoolroom French—is probably the most famous fictional detective since Sherlock Holmes.

When Dame Agatha invented him, she described him as a famous Belgian sleuth who had retired before the first World War. That would have made him about 120 at his death in 1975, a literary event which The New York Times marked by flashing his obituary across the front page.

Dame Agatha admitted that Poirot’s popularity surprised her since he wasn’t “the kind of private eye you’d hire today.” But it is not hard to understand the universal appeal of Poirot or, for example, of the elderly lady’s sleuth, Miss Jane Marple, a character inspired by Dame Agatha’s grandmother and great aunt who first appeared in 1930, solving Murder at the Vicarage. They represent logic in an illogical world. Virtue always triumphs; villainy is always found out. The detective story is thus profoundly moral. Agatha Christie has spun her stories for more than half a century while teaching a lesson in moral responsibility: “It’s what is in yourself that makes you happy or unhappy.”

By the time she died, she had lived to see ‘an Agatha Christie’ become a synonym for a detective story. Tributes to her poured in from every continent. She was called a legend, one whose name would outlive most of her contemporaries, a magnificent source of entertainment.

Perhaps a tribute that said it best was a newspaper editorial that ended: “She gave more pleasure than most other people who have written books.” And that is no mean achievement.

From Reader's Digest June 1977