- HOME

- /

- Culturescape

- /

- Entertainment

- /

Kiran Desai's New Novel Explores What It Means to Belong-and What It Costs

Booker Prize winner Kiran Desai discusses her sweeping new novel, in which she explores themes of migration, memory, love, and the burden of history across generations

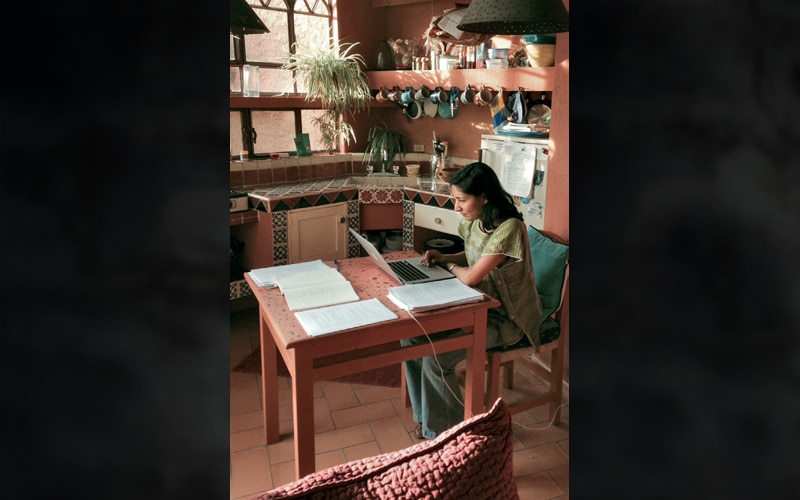

photograph by M. Sharkey

photograph by M. Sharkey

A novel over two decades in the making, by a celebrated young Booker-winning novelist—naturally, there was a great deal of anticipation a round Kiran Desai’s new, nearly 700-page doorstopper The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny. And yet, the book has exceeded those high hopes in style, earning rave reviews around the globe and a place on the 2025 Booker shortlist.

Set mostly between 1996 and 2002, the novel’s two central characters Sonia and Sunny are both Indian immigrants living in the United States. When they were college students, their respective grandfathers (who’re neighbours in Allahabad) launched an unsuccessful matchmaking attempt between the two youngsters. Sonia gets involved with an abusive, controlling older artist called Illan while Sunny starts a relationship with Ulla, who’s more than a little defensive about her rural origins and her white, Republican parents.

Many years later, a fortuitous encounter on an Indian train offers Sonia and Sunny a second chance at love—but can they overcome their personal and generational traumas, to say nothing of the obstacles put up by their respective families? The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny is a slow-burning epic, a novel that never shies away from tackling big ideas. Globalization, xenophobia, America’s ‘war on terror’—all of these themes are beautifully depicted in the novel.

Through Sonia’s work as a budding writer of fiction and Sunny’s job as a journalist, Desai also offers her thoughts on India’s decade of economic reform in the 1990s, as well as the subcontinent’s brutal histories of communal strife and feudal relations.

Reader’s Digest: Take us through some of the historic events used as ‘temporal anchors’ in the novel. What real-world events impact the lives of these characters in direct and indirect ways?

Kiran Desai: In my mind, I was always set that I wanted to start from Sunny and Sonia’s grandparents, who lived and worked in British India. Their children would represent newly independent India’s first steps on the global stage, and their children, in turn, come of age in a newly globalized India, after the economic reforms of the early ’90s. Events like the anti-Sikh riots or the Babri Masjid demolition are referred to during conversations, but they are peripheral to the lives of these characters.

My maternal grandmother was German, and Sonia has a German grandfather in the book. In a subplot that I later edited out, we would meet Sonia’s grandfather in 1940s Germany. I wanted to make the connection between ’40s Germany and the rise of nationalism in India and elsewhere today.

“To me, it is extraordinary that the world is still fighting over religious stories," says Desai.

“To me, it is extraordinary that the world is still fighting over religious stories," says Desai.

When the avowedly progressive (some would say ‘woke’) Sunny meets his white American girlfriend Ulla’s Republican parents, there’s an over-abundance of caution and civility from both sides because they’re both afraid of what the other party will think of them. This scene is set in the late ’90s, of course. Do you think you would have written this scene differently if it had been set in 2025?

I think part of the confusion that Ulla’s parents feel is because they know very little about India and Indians. In 2025 they would have some exposure to the Internet and would therefore have more things to talk about with Sunny. However, we are living in even more polarized times today compared to the 90s. I actually think this might have led Ulla’s mother to be even more polite and civil in a saccharine way—even more caution, from both sides. At the same time, the widespread American anger that we see against immigrants today, and especially Indian immigrants … it would certainly have coloured the opinions of Ulla’s parents, who are Republican voters and are generally old-fashioned, salt-of-the-earth people.

A recurring theme in your work has been the conflict between religious India and secular India, starting from your debut novel Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard (1998), where the protagonist is erroneously thought of as a holy man. How do you see that conversation shaping now, nearly 30 years after that novel was published?

To me, it is extraordinary that in this day and age the world is still fighting over religious stories, essentially. When I wrote my first novel, it was almost like I was trying to recapture a childhood version of India. But the conversations have shifted so drastically since then. In ... Sonia and Sunny, their parents belong to a generation that has made the conscious decision to move away from religion, so that a new idea, a secular nation and society, can succeed. But today even very young people in America and India are moving towards religion in the public sphere; politicians here in America are quoting Bible verses. Look at this kid who was just assassinated [Charlie Kirk]; he was just 30-something, right?

A quarrel over religion is also a quarrel over storytelling, right?

Yes, one of the running themes in the novel is Sonia’s struggle to decide how she would like to tell her story—negotiating fantasy, magical realism and other narrative modes. And that struggle is mirrored in the wider conflicts around religious stories that are also, of course, full of fantastic events.

There’s a scene in the novel where Sonia and her then-boyfriend, the artist Illan, are watching a documentary on the painter Edvard Munch, who endured a series of misfortunes. You’ve written this scene as, at least half, a joke; it’s partly satirical. Do you feel this is an overrepresented stereotype—the perennially suffering artist?

I do feel there’s a profusion of images or stories that paint the suffering artist in a haloed fashion—especially when it’s now clear that there were many great artists and writers who led quite comfortable lives. I mean, if I look at my bookshelf, there’s Marcel Proust, right?

I mean, I listen to Joseph Haydn all the time and by all accounts, he never had a tough day in his life.

Exactly! We must be wary of stories that insist upon artists being miners of pain. The idea that they cannot write or paint or make music in the absence of suffering is a fantasy. And yet, at the same time, I do believe that sometimes, pain can make your art more mature and three-dimensional—how could it not?

The burden of parental expectations has been felt by several Kiran-Desai characters down the years, of which Sunny is the latest. In your view, how are parental expectations different in India compared to America or Europe?

Sunny definitely feels like he has the weight of his mother’s expectations on his back at all time, he is constantly under her gaze. That’s also one of the ways in which the novel is structured—who is looking at who; who feels constrained by whose gaze. But at the same time, Sunny and Babita belong to a very Westernized family. In Babita’s eyes, she is not the typical Indian parent because she has very American ideas of selfhood and insisted her son study abroad and later, work there. Basically, these are parents who have told their children not to look after them in the old-fashioned way … while secretly hoping, of course, that they will be. This creates a gap between stated and unstated expectations—and this kind of dilemma is more likely to happen in India than in America or elsewhere in the West.

Do you have rituals that help you mentally ‘reset’ after a time-consuming project like this one? Having finished a novel of this size, scale and ambition, how do you decide what to tackle next?

It’s not a question of rituals so much as psychologically letting go of the book once it’s out in the world. It’s published and people are now going to make of it what they will—that’s the way it works with books and readers. I am not overly worried about what story I want to tell next. I think I am going to let the next one come to me. Right now, I am just focussed on being in the moment.