- HOME

- /

- Culturescape

- /

- Entertainment

- /

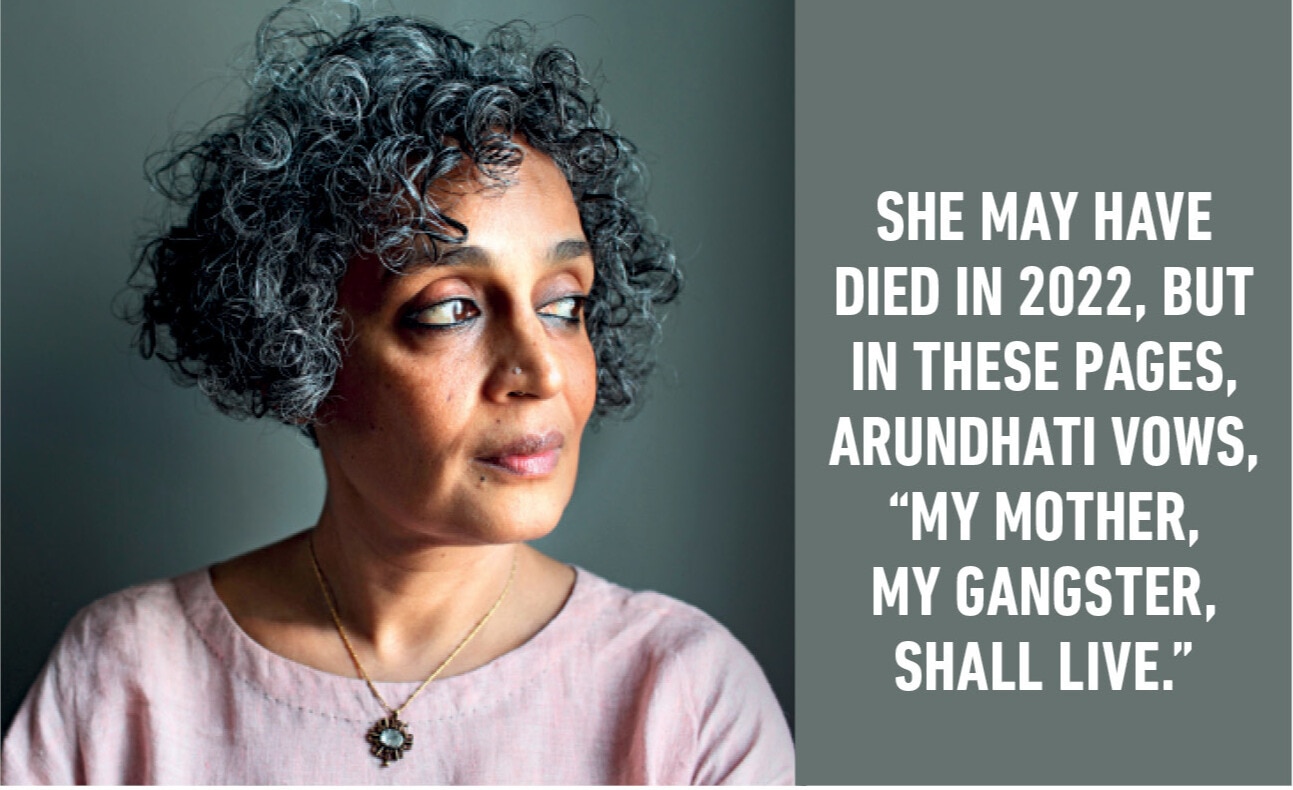

A Life of Defiance: Arundhati Roy's Memoir Reveals the Roots of Her Radical Empathy

Arundhati Roy’s new memoir recounts a life of resistance, survival, and radical empathy, and explores how an accomplished, and complicated, mother shaped her fierce independence and refusal to conform

photograph by Mayank Austen Sufi

photograph by Mayank Austen Sufi

“I never wanted to defeat her,” Arundhati Roy says about her mother. We’re speaking on Zoom, several days before the much-anticipated release of her memoir, Mother Mary Comes To Me, available across India now. In Delhi, at one well-known bookshop, the entire window display has been given over to Roy. Her ubiquity is a reminder of the extraordinary grip she has had on readers’ imaginations ever since The God of Small Things was published, winning the Booker Prize in 1997, as independent India turned 50 and the stage appeared to be set for a newly confident country to emerge from the long shadow of British colonialism.

Mother Mary Comes To Me can be read as a companion text to Roy’s loamy debut, a novel spilling over with human nature in all its variety and pungent excess. In her memoir, Roy indeed chooses not to defeat her mother, not to settle scores, or take the opportunity to have the last word. Instead, she—as she always did—cedes the stage to the formidable, volcanic, Mrs Roy. She may have died in 2022, but in these pages, Arundhati vows, “my mother, my gangster, shall live.” And so Mother Mary ... is both a celebration of a difficult, unequivocally great, woman, and an account of how to survive, or rather transcend, one’s childhood.

In another writer’s hands, Roy’s memoir might have been an extended meditation on the famous opening lines of Philip Larkin’s poem This Be The Verse—with its resigned, hard-won acceptance that parents will inevitably fail, will inevitably do damage to their children, and will inevitably leave lasting scars. But, Roy told me on Zoom—as a well-fed, ageing dog ambled into view behind her—from the time she was very young, she learnt how to dissociate her mother’s public persona, the grand battles she fought, and the private darkness, the violence she visited upon her children.

Roy learnt, in a way her brother never could, how to forgive her mother’s cruelty, her manipulations, her tirades of temper, and her refusal to provide maternal comfort, security and, on occasion, love. “I turned,” Roy writes, “into a maze, a labyrinth of pathways that zigzag underground and surface in strange places, hoping to gain a vantage point for a perspective other than my own.” It was an early education in radical empathy. “Seeing her through lenses that were not entirely coloured by my own experience of her made me value her for the woman she was”, Roy observes. “It made me a writer.”

In the face of her mother’s rage, Roy practised a form of self-erasure, of self-silencing, subsuming her own persona so thoroughly within that of her mother that Roy sometimes imagined herself as a lung, breathing life into her severely asthmatic mother’s decaying body. But Roy’s instinct for self-preservation flickered long enough for her to understand she needed to escape from Mrs Roy, escape from the prison of her mother’s personality.

Mrs Roy—Mary (hence the title)—was a Syrian Christian who married outside her privileged, highly educated if insular community and then found she could no longer live with her husband—a dissolute charmer who managed a tea estate in Assam. Mary took her children to Ooty, where her own father had a house. Once a respected “Imperial Entomologist”, Roy’s grandfather had left behind trunks full of fine clothes and a legacy of vicious violence.

From Ooty, Mary Roy, penniless and nearly defeated, went to Ayemenem in Kerala, her mother’s village. Mary’s brother, G. Isaac, a Rhodes scholar with a Swedish wife and three sons, had already returned to the village, giving up his education to “start a pickle, jam and curry-powder factory” with his mother. It is among this collection of accomplished, overeducated eccentrics and their endless squabbles, that Roy grows up, running as often as she can to the river. “It made up for everything that was wrong in my life”, Roy writes. “I spent hours on its banks and came to be on intimate, first-name terms with the fish, the worms, the birds and the plants.”

For Mary Roy, life in Ayemenem was to come face to face with her inability to do what Indian women were supposed to do—keep her marriage and family together, even at the expense of her own desires and ambitions. But then she starts the school for which she becomes famous. And eventually she takes the legal action for which she becomes even more famous, securing after a decades-long battle the Supreme Court-granted right on behalf of all Syrian Christian women to claim an equal share of her father’s property.

It is impossible not to warm to Mary Roy, who, in her daughter’s telling, is so magnificently contemptuous of tradition. Her brother, G. Isaac, also emerges in Roy’s sympathetic text as a marvellous bundle of contradictions, as capable of generosity and love as he can be of calculating pettiness. Fans of The God of Small Things will recognise Isaac in the character of Chacko. “Anything’s possible in human nature”, Chacko tells his niece in the novel. “Love. Madness. Hope. Infinite joy.” It is the insight that has fuelled Roy’s writing, that arguably encapsulates her entire way of seeing and she learnt it in Ayemenem, in seeing how a family can at once rip itself apart and put itself back together.

That said, Roy fled her family at the first opportunity, heading to Delhi to take up a place at the School of Planning and Architecture. If in Ayemenem, Roy had been the “wild child with calloused feet”, in Delhi she’s the urban version, revelling in her freedom to live as she chooses. The 1989 television movie she wrote—In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones, directed by Pradip Krishen, by then her partner—is a faithful recounting of a rambunctious time, a hopeful, silly moment when the relative poverty of students didn’t mean a corresponding poverty of imagination.

In Delhi, as Roy comes into her own, the reader senses the influence of her mother in her allergy to compromise and convention. Roy, like Mrs Roy, will do as she does and the world will adjust itself around her. It turns Indian convention—in which no one is as impinged upon, as without agency, as the Indian housewife and mother—entirely on its head. Roy’s fierce attachment to independence, to the rights of individuals, can be directly traced to her upbringing, to watching her mother forge her own path, however thorny and unyielding the land.

Mrs Roy’s school Pallikoodam, and its Laurie Baker-designed campus in Kottayam, is a manifestation of her indomitable will. In the same way, Roy’s books and essays are a manifestation of her stubbornness, her congenital inability to fold under pressure. There is no excuse for the terror—verbal and physical—Mrs Roy inflicted on her daughter; no mitigating her words: “You’re a millstone around my neck,” she would say to a prepubescent Roy, “I wish I had dumped you in an orphanage.” But Mary Roy does provide her daughter with a model of defiance, a living, breathing (or rather wheezing) model of how to slough off insults like dead skin.

As we wrap up our conversation, Roy tells me about her disgust with how we’ve become “hateful people”, hiding our hate behind the fig leaf of patriotism. Her books, flawed as they are, and her life, flawed as all of our lives are, have always been a rebuke to those who would talk grandly of abstractions—such as nation, duty, and civilizational values—while paying absolutely no heed to the particular. Roy’s fidelity has always been to the individual and to individual capacity. And it is through this love and acceptance of difference, that both Arundhati and Mary Roy find and build community.

If only, more of us had their spirit.