Two Horrific Attacks, One Forever Love Story

He survived multiple shark bites. She was hit in the Boston Marathon bombing. Then they found each other

Illustration by Guy Shield

Illustration by Guy Shield

Colin Cook remembers the moments just before. Water lapped against his legs as he straddled his surfboard 300 feet from the shore of Leftovers Beach on Oahu. He had been out some two hours already, and he felt exhausted but happy. He looked the part of a seasoned surfer that October morning in 2015. Shaggy reddish brown hair, broad shoulders, lithe build, his 5-foot-10-inch frame snug in board shorts and a wetsuit top.

He’d moved to Hawaii from his childhood home in Rhode Island for moments like this. Out here, at age 25, he could live life slowly. Back east, everyone lived at the frenetic pace of achievement. Almost as an act of defiance, Colin had come out to Oahu and rented a literal walk-in closet in a house owned by the guy he worked for, a manufacturing entrepreneur and a surfer himself. The closet was 4 feet wide and 15 feet long—with the cot Colin bought to sleep on, there was no room to manoeuver. But it was steps from a front door that opened on to the beach.

Colin owned 15 surfboards and acted like a pro surfer even though he wasn’t one. He told himself in those days that he didn’t want to turn pro. He thought competitions would taint what he loved. Instead he glassed—the slow, careful process of fibreglassing and sealing surfboards. It was not at all like the career his dad had as a sports apparel executive and not the life his sister had created as an Ivy League graduate. Amid the beauty of Oahu, Colin tormented himself with questions about why he didn’t have his father’s ambition or his sister’s intelligence. The only answer that quieted his mind, he had found, lived in the barrel of the next wave.

I’m just gonna get a couple more in, he thought that morning in 2015. A couple more waves before paddling in to get ready for work.

Then the force hit him like an 18-wheeler. He was instantly underwater and disoriented from the impact and then above water desperate for breath and then pulled under once more, even more violently. Colin saw the flash of a tiger shark, twice as long as he was, biting down on his left leg. He punched the shark on its nose, again and again and again. The shark thrashed from the blows, butted Colin, then pulled away. He rose to the surface. Panicked, panting, he grabbed his surfboard to try to paddle to shore. He looked behind him for the shark but saw something else.

His left leg, just above the knee: gone. Blood reddened the blue waters.

Colin saw the shark’s fin close on him.

Help!” he yelled. “Shark attack!”

Illustration by Guy Shield

Illustration by Guy Shield

I’m going to die out here, Colin thought.

Already the shark was on him. Colin pushed and punched for his life, and somehow the beast turned away from him again.

The first three fingers of Colin’s left hand hung at nauseating backward and sideways angles.

Colin scrambled on to his board. The open wound of the stump that had been his left leg shot out blood in time with his heartbeat. His vision blurred, darkened. Colin fought to stay awake.

Suddenly, a large Polynesian man stood near him on a stand-up paddleboard. The man clubbed the shark with his paddle until it swam away. He tossed his safety leash to Colin, but Colin couldn’t grab it because of his mangled hand and the blood that dripped from the rope, slickening it.

The shark returned, its dorsal fin parting the water even faster than it had the first two times, the beast more furious than ever.

“Tell my family I love them,” Colin gasped. The man ditched the paddle, heaved Colin on to his back, lay chest-down on his board and swam for it. The shark followed the whole way.

Sydney Corcoran, too, remembers the moments just before. With her parents, Celeste and Kevin Corcoran, she was watching runners approach the finish line of the Boston Marathon on that overcast April 2013 afternoon. Sydney, 17 at the time, wore a sweatshirt and a down jacket. It was 8 degrees but a party there on Boylston Street.

Celeste and Sydney inched between the revellers and the metal fencing the city had erected along the sidewalk. Celeste’s sister, Carmen Acabbo, was running her first marathon, and they all planned to celebrate when she finished. Around 2:45 p.m., Celeste and Sydney jostled their way even with the yellow finish line. As they waited for Acabbo to come into view, it was hard not to cheer for themselves a bit too.

Three years earlier, Sydney had crossed a pedestrian walkway on Massachusetts’s North Shore and was struck by a car. She had bounced off its windshield and hit the pavement so hard that her older brother, Tyler Corcoran, was sure she was dead. Well after Sydney was released from the hospital, the brain bleeding and swelling caused such headaches that she could attend her public high school in Lowell, Massachusetts, only every other day.

By the time she stood close to Celeste at the finish line that April afternoon, Sydney had worked through physical pain, anger, guilt and depression. She finally felt peace. The worst, Celeste said, was behind them.

Then came a noise loud enough to blow out Celeste’s eardrums. She felt as if she’d been flipped in the air. She looked around. Black smoke clouded Boylston Street, blown-out plated glass was scattered across the sidewalk, and blood—blood was everywhere. Celeste tried to sit up and couldn’t. Tried to locate Sydney and couldn’t. Kevin told her he was going to cinch her legs with a belt. She looked down and saw that her legs dangled by the skin around her knees. The blood pumped out in time with her heartbeat. Kevin tied the belt tight, hoping to stanch the flow of blood. The pain was excruciating.

Illustration by Guy Shield

Illustration by Guy Shield

Out of Celeste’s line of vision lay Sydney. A part of the detonation mechanism in the homemade bomb that had just exploded had rocketed through Sydney’s right quadriceps and snicked the femoral artery of her upper thigh. She was bleeding out.

Sydney could feel that something was wrong. Her right leg wouldn’t move the way her brain was telling it to. There was too much smoke to locate her parents. People ran around her. Their faces were terrified. Some were covered in blood.

Where are Mom and Dad? she thought. Am I an orphan now?

Sydney put pressure on her right foot in an effort to stand, and she passed out.

She came to. A Marine was tying a tourniquet made of T-shirts tight around her leg—she gasped from the pain. The Marine told another guy, Matt Smith, to put pressure on the wound in her leg.

Sydney’s thoughts moved beyond the pain. Are there more bombs? Will I survive them?

Her vision blurred, then darkened.

Smith pressed his forehead to hers. “Just squeeze my hand, keep talking,” he said.

She nodded, but time warped. When she came to, she was in a medical tent, erected for marathon runners but now for survivors of the bombing. People told each other, “Her eyes are white! Lips are purple! Get her in an ambulance!”

She wanted to say how much this talk scared her, but she couldn’t speak. She was so cold. Why was her family not here? Next, she was in an ambulance, and pain pulsed through her leg with every pothole and corner while someone hovered in and out of her vision and everything turned white and fuzzy.

I know I’m going, she thought, and I had an OK run.

Colin Cook looked around the hospital room at The Queen’s Medical Center in Honolulu and remembered snippets of the lost hours.

The paddleboarder, his chest to his board, and Colin sure he’d die. Words that floated in a fever dream ...“2 inches above the left knee.” The need to repair the mangled fingers of his left hand. And now this moment, the second day, coming off heavy medication.

My God, I am alive, he thought.

His dad, Glenn Cook, and older sister, Cassie Cook Burns, had arrived.

A doctor entered and said he was there to check Colin’s vitals. Colin took the occasion to peek at his phone.

“What are you looking at, Col?” Glenn asked.

“Watching a live feed of the North Shore’s waves,” Colin said.

Everyone chuckled.

Then the doctor told Colin he’d be lucky to walk again.

Colin stopped chuckling.

Colin took his prosthetic leg in his hands and shimmied and grimaced and pulled until it was on. He was back in his childhood home in Tiverton, Rhode Island. His dad lived here now, and Mary Beth rented a place nearby to help out while Colin recovered.

Colin’s new leg was a heavy, cumbersome, ill-fitting thing, and when he rose in the living room to try to walk, he stumbled to the floor. The nerve endings at the edge of the residual limb were causing him pain. The skin needed to callous over the limb and help desensitize the nerves. Doctors told him it would take time to get comfortable with the prosthetic, but time passed and the situation did not improve. He could not walk more than a few paces before the pain and exertion overwhelmed him and he stumbled again to the floor. Surfing felt further and further away.

Illustration by Guy Shield

Illustration by Guy Shield

Colin’s mother, Mary Beth Cook, arrived next. The two had always been close. Before his parents’ divorce, when Colin was little, Glenn had travelled a lot for work and Mary Beth had found ways to play to Colin’s strengths. That meant dirt bikes for the son who thrilled to danger, as well as carpentry lessons from Mary Beth’s father because Colin could not sit through a school day. His ADHD diagnosis didn’t resolve his troubles in school, which wrecked his confidence.

Always shy, Colin became anxious as the years progressed. He had a few friends but no large social circle, no long-term girlfriend. Mary Beth became his confidante, his centre. She soothed his frustrations as he did his homework. She watched him surf, even in Rhode Island’s frigid winters.

Surfing quieted the story Colin told himself: that he was not good enough. He’d never thought he was good enough to be like his dad or his sister. Just as he’d never thought he was good enough to turn pro. Other elite surfers in Oahu said he had the proficiency. But Colin couldn’t get himself to say it.

The same went for dating. He’d never found a girlfriend, despite his chiselled build and kind manner, because any conversation with a girl turned awkward.

Only Mary Beth and surfing could pull him from his most self-lacerating thoughts. In the hospital room, he drew her close. “Mom, when do you think I’ll be on a board?”

“One day,” she told him. “You’ll be back on your board one day.”

One day that week the muscular Polynesian man who had saved Colin knocked on his hospital door. He said his name was Keoni Bowthorpe. He was 33, with the square jaw and stubbled chin of an action movie star.

Bowthorpe had three small kids and a wife. In the months prior to the attack, he had been tempted by a job on the mainland, he said. Yet some force had told him to stay on the islands. Not just to stay there, but also to grow stronger as a surfer and swimmer.

“God prepared me to save your life,” Bowthorpe told Colin. “And God has been preparing to save your life too.”

Colin wanted to believe he could will his life back to its old existence, but after Bowthorpe left, he searched on his phone for surfers who’d lost a limb above the knee and returned to surfing. He found a few people—in the world. None with a prosthetic that allowed them to surf the way they once did.

There’s no way, he thought.

In the emergency room at Boston Medical Center, doctors told Kevin that they would have to amputate his wife’s legs. He knew Celeste’s life would always be cleaved now into before and after—but that was not the worst of it.

Why hadn’t he been able to find Sydney at the finish line? He had been a few feet behind Celeste and Sydney when the bomb exploded. He’d seen its force blow Sydney back.

Celeste kept asking where Sydney was, and Kevin hadn’t had the courage to tell her that he feared their daughter was dead. Now, with Celeste in surgery, Kevin bawled.

Two hours later, he and Tyler received word: Sydney was alive and here at Boston Medical. Doctors had to remove veins from her left leg to create, in essence, a new artery in her right leg. Soon Sydney was conscious and recovering and, eventually, was put in the same room as Celeste.

Celeste, still groggy from her own surgery, saw her daughter: matted hair, a gray complexion from the blood loss. She looked down at her own legs and what wasn’t there, then reached over to hold Sydney’s hand.

The burgeoning reality of a diminished life followed him and his mother on to a flight to Orlando, Florida, in February 2016. Colin relied on crutches to get around, and his dread trailed him right up to their destination: the 22,000-square-foot Prosthetic & Orthotic Associates.

POA billed itself as different from other prosthetic centres. Its founder, Stan Patterson, had roughly a dozen patents and an on-site fabrication lab where a silicone cast of the residual limb would form the outline of, eventually, the perfect prosthetic, he told Colin. “We’ll have you walking in a week.”

Colin scoffed. Patterson would succeed where the prosthetists up north, with their Ivy League affiliations, had failed?

Patterson sensed Colin’s doubt. He took Colin and his mother to the vast rehab room, where they met a middle-aged patient with pearls and diamond bracelets wrapped around the ankles of her two prosthetics.

Her name was Celeste Corcoran. Her Massachusetts accent made Colin and Mary Beth feel at home. Celeste told them about the bombing and the shared hospital room with her daughter. She had felt a sharp physical pain in the lower legs that were no longer there, a condition known as phantom limb syndrome. What was there had atrophied and seemed shriveled before her, just like her future. At night in the hospital, when she thought her daughter in the bed next to her was asleep, Celeste had sobbed.

Mary Beth remembered seeing Celeste and Sydney on the Today show after the bombing. Sydney’s voice had been hoarse from her being intubated days earlier, but in that interview, they had refused to be victims.

“If you have the spirit and you know that you want to do it—I can absolutely achieve it,” Celeste had said.

Celeste told Mary Beth and Colin how resilient and mature Sydney was. Her classmates at Lowell High had named her prom queen weeks after she was released from the hospital. Sydney chose a strapless, cream-coloured dress, walked in on crutches, and wore her crown when the TV cameras and photographers asked to see it.

As Celeste showed them more recent photos of Sydney, without her prom crown, her beauty still had an almost regal air.

At the end of Colin’s week at POA, Patterson helped him into a new, custom prosthetic. Because of the company’s patented process of using the silicone cast to shape a prosthetic rather than fitting a generic one on to an amputee’s leg, the prosthetic fit snugly, without pain at the nerve endings of Colin’s limb. Patterson demonstrated how to swing his hip to move his leg. Hip swing, step forward.

Patterson walked alongside Colin, then drew back. Colin took his first steps—tentative, unwieldy, still painful steps, but he was walking again. He let loose a yip of a laugh, the way he used to out on the water.

Taking it in, Mary Beth cried and looked at Celeste. She was crying too.

Illustration by Guy Shield

Illustration by Guy Shield

Celeste and Mary Beth became both friends and co-conspirators. In the weeks after POA, after they’d returned to their respective homes, they settled on a goal: somehow get Colin and Sydney in the same room.

Colin was oblivious to all this. The success at POA had refined his obsession. Somehow he had to surf again.

The limited surfing prosthetics on the market all assumed the same thing: The surfer had lost a leg below the knee. An above-the-knee surfing prosthetic didn’t exist. How would a company mimic the ball joint and solidity of the knee and the individualized curvature of any one person’s calf and foot?

From his childhood living room, Colin sketched what his surfing leg might look like. Less a stiff metal rod than the curved blade that some Paralympic sprinters now favor. Its flexion could allow Colin to squat and pivot on the board. What he needed was a curved-blade prosthetic that connected to a ball-socket knee, and then Stan Patterson’s upper-leg prosthetic that fit snugly to Colin’s limb.

Colin had two childhood friends, Brendan Prior and Max Kramers, who were engineers in Rhode Island. He asked whether the carbon fiber they used on manufacturing projects might be used to create his new surfing leg.

The trio’s first iteration of an above-the-knee, surfing-ready prosthetic was fine for standing and walking, but the blade was too long for Colin to squat on his board. The next try had a blade of the right length, but the knee joint wasn’t sturdy.

That wasn’t the only problem. As they made leg after leg, the trio noticed that the carbon-fibre tip of the bladed lower leg—Colin’s new foot—provided little balance when he pivoted laterally. They fit the blade inside a sneakered foot they manufactured, but it slid off wet surfaces.

What about a foamed composite foot? they thought. Something that absorbed water but didn’t slide off the surface of the board.

Within days, the three friends set about creating a foam foot, working with the same composite materials used in high-end sailboat racing. Soon composite feet littered the floor of Colin’s house. He wanted something sticky enough to pivot on a wet surface but not so sticky that it felt glued down. No foot did exactly what Colin needed.

Colin sketched small changes. His mom, who was back in Georgia, where she now lived, kept nagging him about some charity event in North Chelmsford, Massachusetts, but it barely registered. For weeks, Colin kept his focus on his designs, right up until the literal hour his dad told him they needed to leave for the event.

The night was a fundraiser for 50 Legs, a non-profit that helped cover the cost of prosthetics. After the marathon bombing, Celeste Corcoran had received her prosthetics from 50 Legs. She’d be there tonight as an honoured guest, and Colin’s parents told him that her daughter would be there too.

It was a big event, almost 200 people, with hors d’oeuvres, a full bar and a band. Oh, man, Colin thought as he walked into the hall. This is gonna be awkward. In a space this loud and cavernous, he could get so self-aware and ill at ease he’d go mute.

And now here came Celeste—fast-talking, high-energy Celeste—shaking Colin’s hand and introducing herself to Glenn and ceding the floor to Sydney.

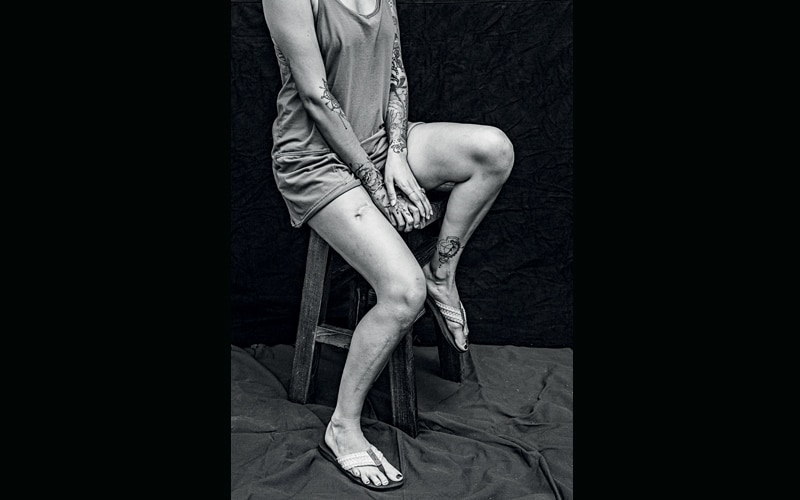

By then, Sydney was 21, more than three years past the marathon bombing, and her black dress cut above the knees made no attempt to hide the surgical scars that ran along her toned right leg. You saw in her eyes what she’d told her mother: She was tired of immature “boys.” She hoped to meet a man, someone who’d been tested by life and was now confident from having endured those tests. The way she’d become.

“Nice to meet you,” Colin said.

He was flustered by Sydney’s beauty, her maturity, above all his ever-nagging sense that whatever he said would be wrong. So he said little.

Sydney walked away.

Later, as Sydney and Celeste talked to stragglers across the room, Glenn decided to intervene. He walked over to Sydney.

“Hey, listen,” Glenn said. “This is how he’s always been. If you want to try to connect, you need to get his number.”

She nodded. Her mother had told her what had happened at POA, how Colin had come to trust that he could walk again. Maybe he’d get why she had a tattoo of a lion across her back and the words ‘choose to live’ on her wrist.She crossed the floor of the hall.

“Hey,” she said when she got to Colin. “If I gave you my number, would you ever text me?”

With the help of two engineer friends, Colin created a surfing prosthetic. Photo: Mike Borchard

With the help of two engineer friends, Colin created a surfing prosthetic. Photo: Mike Borchard

On their first date, Colin could barely eat because of his nerves, convinced he’d say something stupid. Then they went to a movie where they couldn’t talk at all. Colin walked Sydney back to her Volvo SUV and didn’t try to kiss her, didn’t think he deserved to. He watched her drive away, and he got back on the highway to Rhode Island. His phone rang.

Sydney.

She asked if he was still in the parking lot. When he said no, she said that was too bad. If he were, she’d drive back and give him a kiss.

They agreed to a second date, which led to more dates and, for Colin, a sense of unease that he’d somehow screw up a good thing. His anxiety peaked when he drove to the Corcorans’ place north of Boston, where Sydney and her parents had moved after the bombing. It was a large house that had been configured for the wheelchair Celeste used when the pain in her legs became unbearable.

Colin tried to be lighthearted with Celeste and Kevin, but in a moment when it was just Colin and Sydney in the living room, he turned to her.

“Isn’t it weird that I’m an amputee?” As in, How many amputees do you need in your life?

She told him his experience didn’t burden her. She liked it. His life was one she understood. She’d been that close to death too. Now she was here, with him.

In the days ahead, Colin called and texted, more playful in these messages with Sydney than he’d been with any other girl. Meanwhile, he and his buddies kept adjusting his surfing leg and foamed composite foot.

One day he went to the beach and, for the first time, tested the leg. Out among Rhode Island’s low and lolling waves, the knee buckled beneath him. The joint couldn’t withstand his body weight and the water rushing against it. The foot kept slipping off the board. As he swam back, no well of despair rose within him, as it once would have. Was this Sydney’s influence? He didn’t know. He just redoubled his efforts. He and Prior and Kramers tightened the flexion of the knee joint, hoping that a more rigid knee would support him on the board.

Days later, Colin made a second trek to the beach. He felt as if he was close to creating not only a prosthetic that no one else in the world had but also something like a new self.

At the beach, he lifted his board and swam out. On the first big wave, he pushed up … and the foot stuck. He manoeuvered on the board, pivoted, water crashed against him and ... the knee held.

MY GOD, I’M SURFING!

When he got back to land, Sydney was the first person he told.

The more he surfed, the better he felt, until he reached a decision. I want to win competitions with my new leg. I want to turn pro.

To surf as a pro, though, meant that the puny waves off Rhode Island or Massachusetts wouldn’t do. Sydney and Colin decided to move to Southern California, where Colin had extended family and Sydney’s administrative job had an office. Colin found a job designing surfboards in Oceanside, a beach town about an hour south of Los Angeles. They got a place near the water. And bit by bit, their lives fell apart.

It was the distance from Sydney’s family. Her mother was her inspiration, and her brother her best friend. She didn’t feel nearly as poised and confident now as everyone had always assumed she was. There was the bombing, and then the days, months and—she should be honest—years when she relived it. The dread had begun almost immediately after the bombing. She had nearly been killed in a car accident and then again at the Boston Marathon. The universe doesn’t want me here. Death was following her. When she and her mother had shared that hospital room, Sydney stared at what the bomb had taken from Celeste. What had Sydney done wrong in her life for that to happen to her mother?

She thought this all the time. Then her thoughts turned suicidal. The part of Sydney that still wanted to live held fast to the one thing she could still control: what she ate. She would limit it at any meal or, just as often, skip the meal entirely and work out like a fiend.

The thoughts spun blacker in the weeks and months after the bombing, and so the workouts ran longer and the anorexia took a still stronger hold. Then the nightmares began. In one, the most vivid, Sydney crawled through a U.S. Army obstacle course, down in the mud, avoiding the barbed wire above, and then jumped to her feet and ran. Tracking her, gaining ground on her, were the Boston Marathon bombers, homemade explosives in their hands and hatred in their eyes.

She woke yelling and drenched in sweat. She tried therapy for the PTSD and anorexia. It helped. But the dark thoughts returned, or the nightmares did, or the desire to control it all did.

She met Colin and he offered an answer. After his attack, he said, he was never scared of sharks. That astounded her. About six months into their relationship, he even convinced Sydney to travel to Hawaii with him and swim with the sharks there.

She was nervous that day—but Colin wasn’t. With local shark experts guiding them, including Keoni Bowthorpe, Colin got into the ocean miles from the shores of Oahu and swam right next to Galapagos sharks and reef sharks. They were close enough to touch. Back on land, he shrugged it off.

“The ocean is their home,” he said. It amazed her. Inspired her. Colin made her feel good. Strong. Especially when his own insecurities—like a searing self-doubt about making it as a surfer—rose up. Sydney from the start intuited how to buoy him and soothe him.She felt useful around Colin, in other words. She knew him better than he did. She felt loved. And this led her to love him all the more.

But now, in California, the dread returned. She realized she had been able to help Colin only because of how well her mother and father and brother had helped her back in Massachusetts. Her homesickness wasn’t a homesickness at all. It was the severing of an identity. Sydney felt unmoored in California, leading an existence that was as quietly bleak as it had ever been after the bombing.

What made it harder was the way that Colin had thrived out here.

With Sydney’s encouragement, he had found Paralympic-style surfing competitions. The usefulness she offered no longer felt good. She cried every night, most mornings and a good chunk of each afternoon.

“Can you, like, try to be happy?” Colin asked.

“I’m trying. I’m really trying.”

Sydney makes no effort to hide her scars. Photo: Mike Borchard

Sydney makes no effort to hide her scars. Photo: Mike Borchard

By 2019, Colin had won the U.S. nationals twice but faltered both times at the world championship in California. At worlds, the stage seemed too big, with too many other great surfers, too much searing self-doubt.

Sydney reminded Colin as he prepared for the 2020 Paralympic championships—first a statewide competition, then nationals, then, if he qualified, worlds—that he himself talked of how he wanted to be more than the victim of his attack. Winning the world championship would serve as evidence of a man who had not only bested that day but moved beyond it.

“You’ll win when you can believe it,” she told him.

He took regionals and then nationals again, and in mid-March 2020, in what would be the last days before COVID-19 shut everything down, Colin stepped onto the beach of the International Surfing Association’s World Para Surfing Championships, held north of San Diego on the shores of La Jolla.

When he got in La Jolla’s waters for his first heat, his inner critic did what it had always done: quieted enough so Colin could focus on advancing to the next round. It went like this for four days. Colin won and won. In fact, he was the favourite heading into the finals.

On that morning, the fifth and last, he thought about how he would screw this up because that’s what he always did at worlds.

Sydney heard it: the self-talk that he mumbled before the previous two worlds competitions and, frankly, at so many points throughout their four-year relationship. I’m not sure I can do this. Why am I even here?

She looked deeply into his eyes. It stopped the talk and Colin’s pacing.

“You are a great surfer,” she said. “Do this for the love of surfing.”

Soon the three finalists hit the water: Colin Cook of the U.S., Eric Dargent of France, and Naomichi Katsukura of Japan.

Colin let the others take waves, waiting for the perfect one that he alone could ride. The world narrowed until there was only Colin and the waves and Sydney’s mantra: “Do this for the love of surfing.”

The perfect wave crested, and he rode it. Then another perfect one. He rode that too. When he reached the shore, the evidence from the judges was irrefutable—Colin was the world champion for adaptive surfing in the above-the-knee division.

Colin (above) can surf again with his new leg. Photo: Mike Borchard

Colin (above) can surf again with his new leg. Photo: Mike Borchard

Colin and Sydney got married in April 2023 and now live on Oahu. It was a risk, moving still farther west from Lowell, but Sydney has found here what Colin has always cherished. On their afternoon hikes to the top of one of Oahu’s lush mountain peaks, taking in the Pacific, or on their morning walks for coffee, Sydney likes the island’s slowed-down life that dwells on the moment before them, which they’ve learnt is all they really have. She’s better. The dread and, in particular, the severing of self are things of her past.

She’s also taken the advice she gives Colin. She ignores the fear that rises when pursuing the life she wants. She’s quit her nine-to-five—she never liked the corporate life— to make candles that she ships to an ever-burgeoning list of mainland clients.

Surfing was an Olympic competition in last year’s summer Games, and adaptive surfers might be able to compete in future Paralympic Games. Colin is looking toward a time in which he might be Colin Cook, Paralympian. Even he laughs at how big his dreams have become.

Colin and Sydney have built a new life in Oahu. Photo: Mike Borchard

Colin and Sydney have built a new life in Oahu. Photo: Mike Borchard

Sydney still shapes them. She has to. Colin wakes in the morning now wanting to surf but is sometimes terrified that a shark will bite him. The PTSD took six years to surface, and these days, on the worst days, it keeps him from riding the waves. When his panic is a physical pain in his chest, Sydney guides him to the beach. She watches while he latches on his surfer’s leg. Most days she says nothing.

Then he breathes out and, after a nod from her, tiptoes his way into the water. “Just knowing she’s back there ...” he’ll later say but not be able to finish, for how much her presence on shore means to him in the water.

By the time the first wave hits, he’s fine. New Colin.

When he comes in, she’s still there, and the two of them, holding hands, walk home.

Esquire (14 October 2024) © 2024 Paul Kix.

For more thrilling tales of survival, click here.