The Boys In The Cave

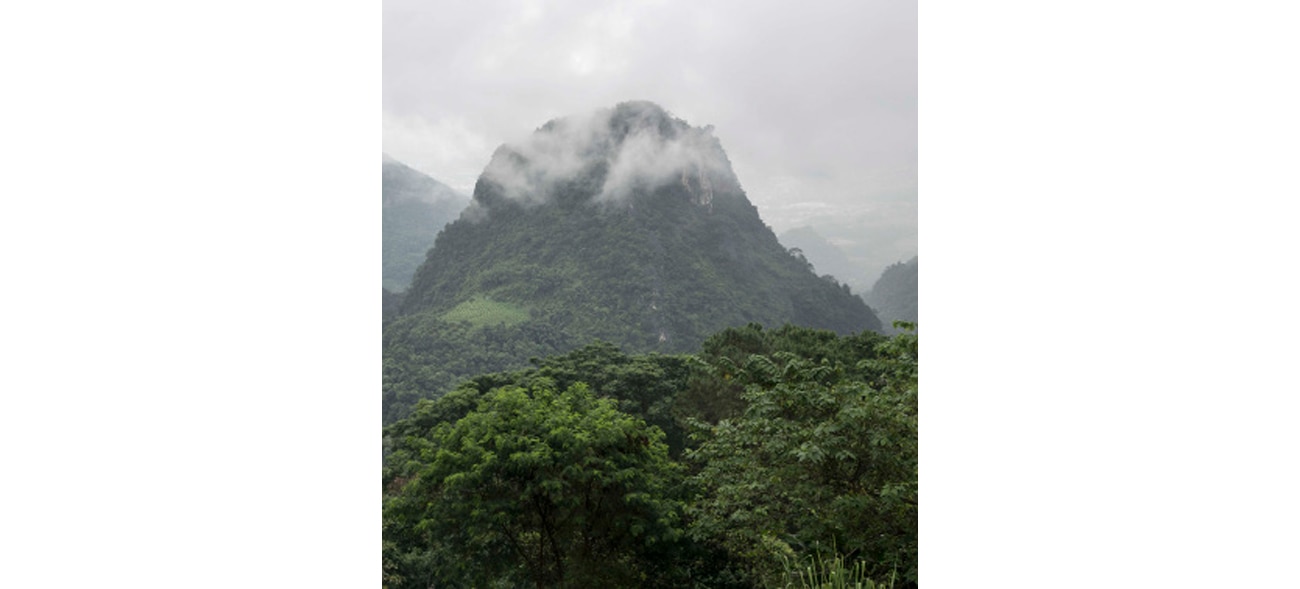

For the soccer team trapped deep in a Thailand cave, rescue seemed impossible

Saturday, 23 June 2018. The 32-de-gree-Celsius air in Mae Sai, Thailand's northernmost town, was like a hot damp towel wrapped around the Moo Pa (Wild Boars) soccer team, but they cycled to the pitch anyway—they always did.

If head coach Nopparat Khantha-vong was the team’s general, assistant coach Ekapol Chantawong—‘Ek’—was his friendly lieutenant. With his smiling eyes and chirpy voice, at age 25 he was more like a big brother to the kids. Having spent much of his childhood in a monastery, as many underprivileged boys in Southeast Asia do, Ek had learnt Buddhist discipline, meditation and kindness.

Ek often took his players to Tham Luang cave at the base of Doi NangNon mountain after practice. A half-hour bike ride away, it was a refuge from the heat and—especially appealing to Ek—the cell signals upon which the boys were hooked. So at noon the group headed there. It was the first time for Peerapat Sompiangjai, nicknamed,as many Thais are, with a shorter name:‘Night’. He planned to be home by 5 p.m. for his 17th-birthday celebration.

Entering the cave they passed a sign that read, in Thai and English, “DANGER!! FROM JULY TO NOVEMBER THE CAVE CAN FLOOD”. Coach Ek, who led the way, wasn’t worried; it was still June and the monsoon rains that would flood the cave’s channels hadn’t started yet. Behind him were Night;15-year-olds Note, Nick and Tee; Bew,Adul, and Tern, all age 14; and 13-year-olds Dom, Pong, Mark and Mix. Giggling among them was the littlest guy, ironically nicknamed Titan, age 11. With Ek, they were 13 in all.

The mouth of the cave was large enough to fit the Taj Mahal. Mud stains some six metres up showed the high-water mark of previous years’ floods. About 1.6 kilometres in they turned left at a T-junction. They wanted to reach Pattaya Beach—a sandbar named after a Thai resort town—more than half a kilometre further in. The boys,marching fast, encountered small passages they had to stoop down and squeeze through. Titan, who was also experiencing the cave for the first time,found himself afraid of the dark and the creepy shadows cast by their flashlights. But he didn’t dare tell anyone.

There wasn’t much to see at Pattaya Beach, but the Wild Boars were happy to have an adventure to celebrate Night’s birthday. Coach Ek checked his watch; they’d been in the cave about an hour. They headed back.

But before they reached the T-junction, instead of the stagnant water they had crossed on the way in, they found deep, fast-moving water. Ek pulled a rope from his bag, tied it around his waist and instructed three of the bigger boys: “If I yank twice, pull me back. If I don’t, you can come too.”

Ek dove down, but the darkness,depth and current defeated him. He yanked twice. Night felt a surge of panic as he helped haul in his coach.

It was now about 5 p.m. The scared boys hadn’t eaten in hours. Worried they would panic, Ek told them something he didn’t believe himself—that the water would probably recede by morning. “You’ll see,” he said. “Why don't we find a place to sleep?”

They retreated to the high sandbar of Pattaya Beach, which typically remained above water during the floods.Ek gathered the boys for their usual Buddhist prayers, chants he hoped would soothe them, before they clumped together for sleep. But the boys’ sobs echoed off the walls.

The Rains Arrive Early

Though the Wild Boars didn’t know it, the monsoon rains had arrived early. And parents grew alarmed when their sons didn’t return home. At 10 p.m., a local team of rescuers was called in and a few parents made their way through the deepening mud to the cave entrance, near where the boys’ bikes stood parked.The ranger wouldn’t allow them to goin, so they shouted into the entrance:

“Night!”

“Bew!”

“Titan!”

The only answer came from the cave: echoes bouncing the names back.

At 7 a.m. on Sunday, 24 June, rescuers entered the cave. Vern Unsworth, a 63-year-old local Brit who came to the cave after receiving many phone calls overnight, knew this place better than anyone. Over several expeditions, heand his friend Rob Harper had created a new, extended survey of the cave system, replacing one from the 1980s.

At the T-junction, Unsworth stopped in his tracks. The bowl that he’d seen so many times was now completely underwater. He’d been told there was water, but didn’t expect this much.There was nothing he could do so he returned to the mouth of the cave.

That second night, the boys were pushed further into the cave system by rising water. In what would later be called Chamber Nine, about 2.3 kilometers from the entrance, the muddy ground slanted sharply up toward the cave wall. A flatter area served as living and sleeping quarters. Whenever a boy started to cry, the others would hold him and try to cheer him up.They were cold, hungry and scared,and Ek helped them stay calm with regular prayer and meditation. They had no food but the stream below gave them water. Tee held his mouth open under a stalactite and swallowed drop after drop until he felt full.

This was only the start of a more than two-week ordeal.

Where Were the Boys?

Days went by and still nobody knew where the boys were, or if any had survived starvation, hypothermia, or drowning. Thai SEALs—the navy’s elite force—had failed to find them. A thousand troops and helpers gathered outside the cave, and the world watched news reports, hoping for a miracle. But as waters rose, the military suspended rescue attempts.On 28 June, the fifth day after the boys entered the cave, an expert in water management, 32-year-old ThanetNatisri, began an operation to divert water on the mountain above the cave with pipes and pumps so that it didn’t seep into the cave. It made the difference; the tunnel became navigable.

On day 10, Monday, 2 July, a pair of the world’s best cave divers who had flown to Thailand would attempt to find the boys. Vern Unsworth had drawn a map of where he thought the boys could be, and the newly arrived rats—Rick Stanton, 57, and John Volanthen, 48—committed it to memory. Then, for three hours they finned against the current, breathing heavily into their regulators and carefully unspooling a thin guideline behind them.Basic diving protocol, the line was their link to the outside world. They were farther into the cave than any of the rescuers before them could get.

Stanton checked his air gauge; he had consumed about a third of his supply, which meant they had to turn back soon. Cave divers use a third of a tank on the journey in and a third on the journey out, and reserve a third in case of trouble, like getting lost or stuck. Death can result from equipment failure, flash floods, slamming headfirst into rock—and panicking.

They passed Pattaya Beach, which water had swallowed up. Unsworth’s guess had been that the boys had taken refuge a few hundred yards beyond in a room that offered high ground.

Stanton and Volanthen were veterans of multiple cave rescues; some were successful, but more often they found corpses. To their knowledge nobody with zero provisions had survived this deep into a cave for this long. They figured that, sadly, wherever these boys were, they weren’t alive.

Stanton made a mental note to tell Volanthen they need to turn around soon. Then he surfaced, took off his mask and sniffed. Along the way,when the men had noticed air spaces above, they would bob up and take a sniff, their noses supplying information their eyes couldn’t. This time,there was the distinct smell of either human excrement—or decaying bodies. “Hey, John,” he said in the dark.“We’ve got something.”

Then, voices. As they drifted toward the sound, they saw a beam of light flick on and scan the water.

“When Will You Be Back?”

Moments earlier, Coach Ek had heard something: men’s voices.The boys stopped cold as Ek asked everyone to hush. Silence. Then the voices again.

The boys were unsure if what they were hearing was real. They so zealously conserved their flashlight batteries that they’d mostly been in complete darkness. They knew by their digital watches that ten days had gone by. Oxygen was dwindling, and sleep came fitfully; they longed for food, their parents, their beds.

Too tired to move, Ek whispered to13-year-old Mix to go to the water’s edge with a flashlight to check it out.“Hurry. If it’s a rescuer they might passus.” Now the boys saw two creatures that looked like spacemen with hoses attached to their mouths, and helmets bristling with lights. The semi-submerged figures were talking. Mix froze with fear.

Adul, 14, took the flashlight from Mix, and called out in Thai, “Officer! Officer, hello! Over here!” The voices didn’t answer.

Adul, stupefied that they had been found, was doubly confused when herealized the men were speaking English. He crept to the water’s edge. He could speak some English, but right now could only muster a “Hello!”

The divers first surfaced about 45 metres away. By 20 or so metres out,their headlights illuminated a couple of the Boars. “How many are you?”shouted Volanthen. “13!” came the reply. “Brilliant,” said Volanthen. They were all alive. He added, “Many people are coming”—though that promise would later dog Stanton and Volanthen with the sting of guilt. The more they came to understand the boys’ predicament, the less optimistic they felt.

“I am so happy,” Adul told them.“We are happy, too,” replied Volanthen.They went onto the sloping mud bank and stayed about 20 minutes. Stanton inspected their living quarters, the ten-foot-long ‘escape tunnel’ they had been digging, and the sleeping area they had leveled out. When one boy asked with a hint of desperation when they'd be back, the men responded,“We hope tomorrow.”

“We are hungry,” said the boys lifting their soccer jerseys to reveal bony ribs. The divers hadn’t expected to find them alive and had no food for them. Stanton took stock of the group.The little ones and the coach seemed lethargic and frail, but some of the bigger boys looked surprisingly energetic.

As the men prepared to leave, each boy came over and wrapped skinny arms around them. In a country where physical contact among strangers is unusual, where hands pressed together in front of one’s face takes the place of a handshake, the embraces showed the enormity of the boys’ relief and gratitude.

As news spread that the Boars had been found, cheers rang out at the camps of soldiers and volunteers that had sprung up around Mae Sai. In the park ranger hut the boys’ parents high-fived and hugged.

The next day, seven Thai SEALsmade the perilous journey, bringing space blankets, medical supplies, and energy gels to the boys; four of the men stayed behind with them. A day later, Volanthen and Stanton delivered military ration packs. It was the first food the boys had seen in 12 days.

With food in their bellies, the boys’ vigour returned. To pass the time, they played checkers with the SEALs using clods of dirt and rocks as pieces.An American military para rescue team, called in from their base in Okinawa, Japan, was placed in charge of rescue-plan logistics. One option—leaving the boys in the cave for months,until after the monsoon season—was dismissed when an oxygen reading in the boys’ chamber showed just 15.5per cent; it meant there was no way the boys could survive that long.

Volanthen and Stanton knew that only a handful of cave divers in the world could survive the round-trip journey as they had; they suspected bringing the boys out could be impossible. A plan was then decided: the Boars would be sedated. Otherwise,if a boy panicked, he and his rescuers could die. The linchpins of this effort would be two Australian divers who were also doctors, veterinarian Craig Challen and anesthesiologist Richard Harris. In all, about a dozen divers, working in shifts over three days, would be needed to swim the13 out: four on each of the first two days, and five on day three.

Two of the lead divers flew in from Britain: Jason Mallinson and Chris Jewell. On Friday, 6 July, the pair delivered food and wet suits to the boys.Hours later they arrived back at camp with notes from the boys to their families, possibly their last communication. Eleven-year-old Titan had written,“Mom, Dad, Don’t worry, I’m OK, please tell Yod to prepare to take me to eat fried chicken. Love you.”

A High-Risk Mission

Before the rescue could begin, hundreds of air tanks had to be hauled to points along the extraction route. Flexible plastic stretchers called Skeds, which wrap around a casualty like a taco, were dropped off in Chamber Three; the boys would be put on them for the last treacherous stretch before the cave entrance.On 6 July, Saman Gunan, a square-jawed ex-Thai SEAL, was ferrying air tanks in the sump between Chambers Three and Four, his last dive of the day. His dive buddy turned around to find him unconscious. He couldn’t be saved. No one knows exactly why, but he had run out of air. Gunan’s death unnerved everyone.

On Saturday, 7 July, the day before the rescue was to start—and two weeks since the boys had entered the cave—Harris and Challen made their way to Chamber Nine to examine the boys and calculate how much sedative each one would need. Some had symptoms of chest infection, but they and their coach seemed relatively healthy, if rail thin. The doctors also brought letters from the boys’ families. “Dad and mom are waiting to arrange your birthday party,” Night’sparents wrote. “Please get out soon,and stay healthy."

Harris would administer a sedative so each boy would be calm before setting off. Then at dive time they would get two injections: ketamine to knock them out and atropine to dry up their mouths and lungs so they wouldn’t choke on saliva. It was likely that each boy would wake up a few times during the three-hour extraction as the medication wore off,and would need to be re-sedated by their diver. So each diver was given a crash course on how to administer a new shot of an aesthetic.

Despite the meticulous planning,the rescuers knew that some casualties were likely. There were just too many things that could go wrong.

Without fanfare, at 10 a.m. on Sunday, 8 July, the lead divers—Challen,Harris, Stanton, Volanthen, Mallinsonand Jewell—slipped into the water at Chamber Three, spaced a few minutes apart. Harris would stay in Chamber Nine all day. Mallinson had volun-teered to be the first to lead a boy out.

When they reached Chamber Nine,Note was readied for the trip. Harris administered the shots, and after Note lost consciousness, Harris and Mallinson zip-tied his limbs to prevent them from getting injured or entangled, and strapped on a positive-pressure facemask. It would feed air continuously to ensure the boy kept breathing while comatose. Harris tested the mask seal by dunking the boy’s head into the water. But Note had stopped breathing. Then, an eternal 30 seconds later,bubbles flowed from the side of his mask, indicating exhalations.

With an oxygen tank now secured around Note’s waist, Mallinson gripped the two straps on the back of the boys inflatable vest and started kicking, following the guideline. The first section was the longest—a 20-minute, 320-metre swim. Toward the end was a chokepoint; Mallinson had to contort Note’s body to get him through it.

Note’s head, facing down, inevitably struck unseen rocks. His bare feet dangled low and scraped the sharp rocks and gravel on the tunnel floor. But Mallinson’s mission wasn’t necessarily to bring the boy out uninjured; it was to bring him out alive. His sole focus was the mask’s seal. If it became dislodged, Note could drown.

Soon after the two emerged in Chamber Eight, Volanthen, who had been behind them, arrived with Tern.They were followed 20 minutes later by Jewell with Nick. Then one by one each diver and boy entered the sump at Chamber Seven and kept going.

This photo captures the moment when cave divers discovered that the group was alive

This photo captures the moment when cave divers discovered that the group was alive

“There’s Nothing We Can Do!”Back at Chamber Nine, Harrisdosed the day’s last boy, Night,with ketamine. For a few moments he stopped breathing—then came a slow breath. Stanton nosed into the canal with the boy, watching carefully for the bubbles that indicated breathing. Some 50 metres out, he shouted back to the doctor:“He doesn’t seem to be breathing much!” Night was taking maybe three breaths a minute.

Harris shouted back, “There’s nothing we can do, keep going!”

With four boys on their way out, Harris now set off. Arriving in Chamber Eight just after Stanton, he saw that Night was blue and cold, barely breathing. Harris lay cheek-to-sand and cradled the boy’s head, trying to keep his airway open. This is going really badly,he thought. But then Night began to take sporadic breaths and soon his breathing stabilized—in fact, he was coming to. Harris knocked him out with another ketamine jab, and Stanton resumed their journey.

Ahead, Mallinson, the first diver,was leaving Chamber Seven when he felt Note twitch—he was coming to.In neck-deep water, he pinned Note against a wall while trying to get the ketamine from his bag, but when he found it, the syringes popped out,slowly floating away. Mallinson managed to grab one, and injected Note.

The last and most challenging chokepoint was a narrow vertical squeeze from Chamber Four to ChamberThree. Visibility was poor, and feeling their way was even more difficult when holding both the line and a boy.

Mallinson had memorized the squeeze. He pulled Note upright, stuffed him through the narrow opening and slid in behind, careful not to let go of the boy. It was one of the darkest parts of the dive, and Mallinson hoped his banged-up ward was still alive.When they arrived at ChamberThree, the second-last one before the entrance, Note was unresponsive.A Thai doctor stationed there assessed his vitals.

“He’s alive!” came the call.There was a burst of cheers from surrounding rescue team members.

Now some 1,000 metres more had to be covered to get Note out. First he was strapped into a Sked, which was harnessed to a newly built rope-and-pulley system that would enable the boys to be lifted over a series of boulders. After that, the Sked was carried by another team for more than 60 metres around stalagmites and boulders. Then, Thai SEALs maneuvered the stretcher via another rope system down a 45-degree slope to a pararescuer, who carried the boy to Chamber Two. On the final stretch, another Thai SEAL team hauled Note through 365 metres of chest-high water, and then ran him to the cave entrance.There, Note was exposed to his first rays of natural light in more than two weeks.

As the boys—first Note, then Tern, Nick, and Night—emerged, ambulances moved them away from the Tham Luang cave and they were helicoptered to a hospital in ChiangRai. At that point, even their parents weren't aware of the rescue. But it wasn't long before the news leaked:Four of the boys were out, and they were all alive.

While the world was learning about the divers’ incredible feat, Mallinsonand the rest of the exhausted team were busy preparing for the next day’s dive, when they’d try to bring four more boys to safety. Nobody could stop yet—there were dozens of empty tanks to refill and replace, ropes to be tensioned, and much more.

An Unlikely FeatThe human shuttle continued for two more days. On the second day, Nick, Adul, Bew, and Dom were brought out without a single incident or scare. Harris told a rescue planner, “Man, this has never been done before. We’re actually succeeding at mission impossible.”

But they all knew they couldn’t be complacent. There was a new threat:The forecast was for more rain on the third and final day, possibly five centimetres. The rescue would be suspended if there was too much;it could overwhelm the pumps that were continuously extracting water.But if that happened there was no telling how long they’d have to leave the remaining boys, Ek, and the four Thai SEALs in Chamber Nine.Next morning—Tuesday, 10 July—there was a break in the rain. It was now or never. They started an hour ahead of schedule. When the divers passed the T-junction they were relieved to see no clear water in the current —Thanet’s diversion system outside was still working.

Later that day, the last boy, Pong,was carried from the cave and taken to hospital, where he, his teammates,and their coach would remain under observation for a week. Then, the four SEALs made their way out.

As the rescue teams emerged from Tham Luang cave to huge crowds,cheering and shouts of “Heroes!” and“Thank you!” drowned out the rain.The boys’ parents cried tears of joy.It was over.

Just hours later, the monsoon rains totally sealed off Tham Luang cave.Only the divers and doctors really understood how unlikely this rescue was. They had done something unprecedented: extracted13 unconscious human beings through more than two kilometres of jagged, flooded tunnels without a fatality. Military and civilian, Thai and international,the rescue teams had achieved the impossible. The mission had met its objective: The Wild Boars were going home.

Several weeks later, the boys rode their bikes up the hill to Coach Ek’s small temple dormitory to celebrate Titan’s 12th birthday. It was nearly 9 p.m. when the boys cheerily bid Ek goodbye and pointed their bikes downhill toward home—betraying not a speck of fear. They were, after all,the Moo Pa.

excerpted from the book the boys in the cave by mattGutman, copyriGht © 2018 by matt Gutman. reprinted with permission of harpercollins publishers.

In 2019, the King of Thailand granted royal honours on 75 Thai and more than 100 foreign rescuers who took part in this remarkable feat—including people from Belgium, the United Kingdom, Laos, Canada, Denmark,Finland, China, Germany, Japan,Singapore, Ukraine, and the United States. The King honoured SEAL Saman Gunan with a posthumous promotion and sponsored his funeral.

British divers John Volanthen, Rick Stanton, Chris Jewell, and Jason Mallinson received gallantry medals from Queen Elizabeth II. Vern Unsworth was appointed an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) for his role in the rescue. Craig Challen and Richard Harris were jointly named 2019 Australian of the Year.A Hollywood film called Thirteen Lives (directed by Ron Howard and starring Colin Farrell as John Volanthen and Viggo Mortensen as Rick Stanton) is set to be released in spring 2022