- HOME

- /

- True Stories

- /

- Crime

- /

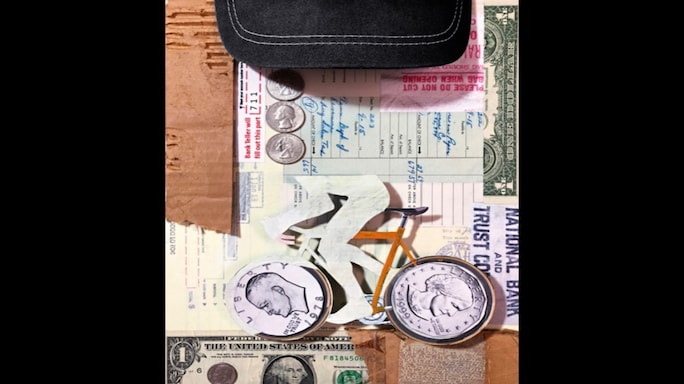

The Bank Robber On The Bicycle

Tom Justice chased Olympic gold on his bike. Then he used it as a getaway vehicle

The man in the baseball cap and sunglasses waited for the teller to notice him. The morning of 26 May 2000, was quiet inside the La SalleBank in Highland Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.

“May I help you?” said the young woman behind the counter. The man reached to the back of his khakis as if to fish out a wallet. Instead, he presented her with an index card. The teller's smile wilted as she stared at the words: “THIS IS A ROBBERY. PUT ALL OF YOUR MONEY IN THE BAG.”

The robber, a slender man wearing a blue oxford shirt, returned the card to his pocket. “Nice and easy,” he said coolly, handing over a plastic shopping bag. While the teller anxiously transferred bundles of cash, the man gently pressed his palms together as if he were about to whisper “Namaste”.

“Thank you,” he said and walked out the front door.

Less than two minutes later, he emerged from an underground parking lot carrying a bicycle on one shoulder and a messenger bag over the other and wearing a red, white and blue spandex bodysuit. He climbed onto the bike and began to ride leisurely.

He cruised up to a trash can. After fishing two crisp $20 bills out of the plastic bag, he held it upside down over the can. Several bundles of cash—$4,009 in all (around `1,74,390at the time)—tumbled into the trash. The man returned the empty sack to his messenger bag and pedaled away.

Seated in the bleachers, 13-year-old Tom Justice watched in awe as the cyclists careened around the outdoor track of the Ed Rudolph Velodrome, outside Chicago. Every time the pack whirled by, it cut the air, unleashing a concentrated whoosh.

Before that summer of 1983, Tom had never seen a bicycle race, let alone a velodrome. But from the moment he entered the stadium, he was transfixed.

He returned a week later with his maroon Schwinn [bicycle]. As the stadium lights buzzed, a dozen suburban kids gathered on the track. Everyone was wearing T-shirts and gym shorts except for Tom, who stood out in the professional-grade jersey and padded cycling shorts his father had just bought him.

Tom won the 12- to 14-year-old heat handily. Straddling his bike, his chest still heaving, he felt a surge of adrenaline. He had finally found something at which he excelled. His father, Jay Justice, a Navy veteran with an abundance of athleticism, was thrilled.

By Tom’s junior year at LibertyvilleHigh School, his identity hinged on cycling. In 1987, just four years after his first velodrome victory, Tom was selected to attend the Olympic training camp in ColoradoSprings, Colorado.

In the school’s 1988 yearbook, one page asked, “What will your friends doing in 10 years?” Tom Justice’scaption read: “On the cover of a Wheaties [cereal] box, with his bike.

”But after high school, Tom’scommitment to cycling—and everything else—lapsed. Instead of training, he broke into empty houses to smoke cigarettes and chug beers with his buddies.

Somehow Tom still harboured grandiose expectations. And since nothing else ever clicked for him the way cycling had, after graduating from college, he moved to Los Angeles to train alongside the US Olympic team. He did little to distinguish himself. The other sprinters could tell he lacked discipline. “Tom’s fast, but he doesn’t train right,” one noted.“He needs to apply himself.” He soon washed out, returned to Chicago, and found a job as a social worker. Helping people was a welcome distraction from his own issues. But after a while, it felt like a pointless slog.

As Tom’s Olympic dream slipped away, he fantasized about identities he could substitute for the thrilling instant gratification of cycling. He made a list and then wandered from inter-view to interview, growing increasingly unhappy with his mundane life.

Late one night in 1998, Tom revisited the list he’d added to over the years. Under ‘helicopter pilot’ and lock picker’, he’d scrawled two letters:‘B.R’—Bank robber.

Tom’s fascination with bikes started early. He had this one when he was four.

Tom’s fascination with bikes started early. He had this one when he was four.

Several notorious American bank robbers had spent time in Chicago. That history added to the allure for Tom. At a wig shop in the same neighbourhood where gangster JohnDillinger hid out, Tom considered his options. Ultimately, he settled on black braids with short bangs that made him look like ‘Super Freak’singer Rick James.

On 23 October 1998, Tom entered his parents’ garage, grabbed his messenger bag and Fuji AX-500, and pedalled towards downtown Libertyville. He coasted up to a tree-lined fence between two houses and slid on a pair of khakis and a blue oxford button-down over his cycling spandex. He slipped on his wig and dark oversized sunglasses reminiscent of JackieO’s and then continued on foot to the American National Bank branch.

When Tom approached the teller, she perked up immediately. Halloween had apparently come early this year. Then the love child of Rick James and Jackie O handed her an index card but wouldn’t let go of it. As an awkward tug-of-war ensued, the teller leaned in and read the message. Tom slid his plastic bag across the counter, and she loaded it up with cash. Tom strode outside bag in hand. His heartbeat surged. His legs tingled. Two minutes later, he was beside his bike, feverishly stripping down. He shoved his disguise and the money into his messenger bag.

Then he casually cycled back to his parents’ house. He parked his bike in the garage and tiptoed into the basement. Kneeling on the shag carpet, he looked at the money and began to weep. It had been a long time since Tom had felt this alive—or this important.

For months, that $5,580 (`2,30,230that year) he’d stolen sat in a gym bag inside the closet of his old room at his parents’ house. Tom assumed the bills were traceable, so he kept only two $20s as souvenirs. Late one night, he tossed the remaining cash into a few dumpsters.

Nearly one year after his first robbery, Tom committed his second. This time, he discarded the bills in alleys where he knew homeless people would find them. Robbing banks and giving away the money were intoxicating. Tom saw himself as both mischievous and righteous.

But that feeling faded. Tom’s real life seemed mediocre and unfulfilling. He wrestled with depression and brooded over the realization that at 29, his window of opportunity to become a world-class cyclist had nearly passed. If he wanted to pursue his Olympic dream, he had to do it now.

He told his girlfriend, Laura, he was moving to Southern California to train for the Olympic trials. He had retained his classification as a Category-1 cyclist, so he would automatically qualify for the trials.

When he arrived in California, Tom looked in the mirror and told himself, “I’m not going to rob any more banks.”

"How’s it going?” asked Laura, calling from Chicago.

“Well!” replied Tom. His skin was tan from his time at the San Diego Outdoor Velodrome. Every morning, he worked through the Olympic strength-training regimen to build muscle mass. His already explosive dead start was getting deadlier. As the weeks passed in early 2000, Tom rounded into the best shape of his life.

But the monotony of training was setting in. The day after Valentine’s Day, he hit a bank in Encinitas. On 29 February, one in Solana Beach. The next day, another in Encinitas. Two weeks later, one in San Diego. On 24 March, Tom robbed two banks, nabbing his biggest score yet:$10,274 (`4,61,713 at the time).

Then one morning, an intense pain surged through Tom’s lower back. He’d thrown it out overtraining. It would take weeks before he could pedal without waking up in agony the day after. His plan to race in the Olympic trials was over.

Soon after he returned to Chicago, Laura dumped him. He moved into an apartment with George, a 104-kilo Greek hulk who worked nights.

“What do you do?” asked Tom.

“I’m a cop,” said George.

Once his lower back recovered, Tom robbed the LaSalle Bank in Highland Park—the heist in which he dumped his $4,009 haul in a trash can. The next week, he hit three banks in three days. George had no clue his roommate had just knocked over his13th bank.

In the summer of 2001, Tom joined a club cycling team run by Higher Gear, a bike shop not far from the LaSalle Bank. One day, the shop's manager mentioned to Tom that a local rider was selling a usedSteelman. Steelman bicycles are exceptional. Tom, whose own bike had recently been stolen, was looking for a replacement. As soon as he saw the Steelman, he was torn. It was painted a garish Day-Glo orange. But he knew that a used Steelman didn’t just magically appear every day, so he bought it.

By this point, Tom had stopped giving away the cash from his robberies. He was becoming dependent on drugs. He had no job, but he had pockets full of cash and cocaine. As he increased dosages, his post-high depression deepened.

Tom started attending Narcotics Anonymous meetings. When it was his turn to share, he talked about merely experimenting with drugs. He was in denial. “This is gonna be my last meeting,” he announced after just six weeks. He said he was moving back to California. He was planning to apply to grad school there. Everybody in the room wished him luck.

“Two-eleven in progress.” The voice crackled through the radio in Officer Greg Thompson’s squad car. Someone had just robbed a Union Bankin Walnut Creek, California. It was 7 March 2002, a drizzly day. Thompson was passing a parking garage when a bicyclist shot out of the driveway and flew behind the cruiser. Thompson squinted into his side mirror. The cyclist looked like every other weekend warrior, except for one detail: the messenger bag draped over his shoulder.

As a teenager, Tom qualified to compete in the Olympic trials as a track cyclist.

As a teenager, Tom qualified to compete in the Olympic trials as a track cyclist.

An 18-year police veteran, Thompson taught new recruits to thrive on instinct. This was one of those moments. But before he could flash his lights, the cyclist pulled over, hopped off his bike, and started fidgeting with his back wheel. Thompson parked a few feet ahead and walked back to the cyclist. Tom pretended to adjust his brakes before climbing on to the bike and clicking his left foot into the pedal.

“Do you mind if I take a look in your bag?” Thompson asked.

“Yeah, no problem. I just have to un-clip,” replied Tom. “These pedals are actually counterbalanced, so I need to click into both in order to get out at the same time.

”There’s no such thing as counter-balanced pedals. But Thompson didn't know that. He watched as the cyclist lifted his right foot, clicked down into the pedal, and—whoosh!—bolted into the street in a dead start as hellacious as any Tom had ever mustered on a velodrome.

A few blocks away, Officer Sean Dexter was sitting in a squad car when he spotted a cyclist on an orange bike charging through traffic towards a red light. Dexter pulled into the intersection, but the cyclist didn’t stop.

Tom swerved around the police car, crossed two lanes, and hopped the curb. Darting through a parking lot, he headed towards a tall fence bordering a thicket of 15-foot-high bamboo.

Dexter reached for his radio, but before he could even open his mouth, another cop hopped on the channel. “A guy on a bicycle just ran from me!

” "I’ve got him right here!” Dexter shouted into the radio.

Dexter got out of his car and paced towards the fence. He slowly cracked the gate and peered into the jumbled mess of vegetation. A creek flowed30 feet below, amid fallen tree branches, dry brush, and piles of wet leaves.

Sirens blared as officers secured the perimeter. While Dexter and Thompson walked the upper banks, police dogs combed the creek. After about 15minutes, a detective spotted something in the leaves: an orange bicycle. Then a German shepherd from the K-9 untied them to a pair of cycling shoes hidden under a concrete retaining wall beneath a bridge.

As the sky grew bleaker, the search was called off. They had one good clue, though: the orange bicycle.

Tom was lying facedown in a cold, damp dirt tunnel. Hours earlier, as the orange Steelman tumbled through the brush, Tom had slid down the embankment, crashing violently through the leaves. He trudged 50 feet upstream and took cover underneath a bridge, where he discovered a two-foot-wide hole at the water’s edge. He crawled in headfirst and squirmed 11 feet to the narrow tunnel’s end. Panting in the dark, he heard sirens, then faint voices, and the jingling of a dog's tags. Tom assumed that was the end. But then—a miracle. The cops gave up the search.

It was dark when Tom emerged. He had parked his 1983 Mercedes-Benzabout three kms away. He found it and drove to his apartment in Oakland.

“Is everything OK?” asked Tom’s roommate at the time, Marty.

“Yeah, just a rough couple of days,” Tom replied.

A six-foot-five opera singer, Marty wasn't looking for a new friend, but he'd found one in Tom. Marty knew Tom was snorting cocaine, but he was unaware of his other vices.

“What’s going on?” asked Marty.

“I can’t say,” Tom said.

“Tom, you can tell me anything.

”Eventually, Tom reluctantly told Marty everything.

“What are you gonna do?” Marty asked.

“I need to buy a ticket home,” Tom said. He wanted to see his parents before the cops found him.

Although he didn’t know anything about bikes, Officer Dexter had a hunch that the orange 12-speed was special. He walked it from the station to a nearby bike shop. A guy behind the counter said the frame was custom-made by a man named Steel-man. Dexter called the company and spoke to Steelman’s wife, who handled the bookkeeping. She told Dexter that the serial number he had might be for a 1996 orange bicycle sold at a shop called Higher Gear in Chicago.

Dexter called Higher Gear, but the guy who answered said they didn’t keep records that far back.

Meanwhile, the FBI was doing its own investigating.

A month later, the manager of a bicycle shop in Chicago called the Walnut Creek police. In 1996, he’d assembled the orange bike. He knew the original owner and the guy who'd bought it secondhand.

Tom and his father sat in the kitchen. It was less than a week since Tom had confessed to Marty.

“How’s that job of yours?” Jay asked his son. “What’s your plan for the future?” As far as he knew, Tom was working as a bike messenger.

“I’m gonna apply to some new grad school programmes,” Tom replied.

Jay nodded. Sounds familiar. Tom headed out the door. “See you guys later,” he called, and he climbed into his car.

Left: Tom while he was living with a cop—and robbing banks. Right: the Steelman bike.

Left: Tom while he was living with a cop—and robbing banks. Right: the Steelman bike.

When the first police car appeared behind him, Tom didn’t think much of it. Then there were three more. Redlights were now flashing. Tom pulled over and glanced back. Five cops were aiming their guns at him.

As the handcuffs tightened around his wrists, Tom wanted to cry, not out of despair or fear but out of a much heavier sense of something he wasn’t expecting: relief. After four years, his self-destructive cross-country loop was finally coming to an end.

In the interrogation room, an FBI agent placed a photograph on the table. It was a security-cam shot of Tom. The orange Steelman had led them right to him. Riding an average bicycle, Tom might never have been caught. He gave a full confession. In all,he had robbed 26 banks and stolen$1,29,338 (`62,87,120). He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 11 years. After being released, Tom returned to cycling at his local velodrome. He also eventually found a job at a doughnut shop. Little do the cops know that the 49-year-old handing them their chocolate glazed is one of the most prodigious bank robbers in history.

CHICAGO (29 January 2019) in partnership with EPIC MAGAZINE. © 2019 by Vox media, llc.