Nightmare Alley

A couple, fleeing the shelling in Ukraine, are captured by Russian troops. It’s up to their frantic son—living 2,400 km away—to get them free

illustrations by Owen Freeman

illustrations by Owen Freeman

When Russian soldiers opened fire on our car, I thought we were dead. It was 4 March 2022, eight days into the invasion of Ukraine. My wife and I had hurriedly packed all our valuables that could fit in one suitcase and a couple of carry-ons. We hired a driver, thinking we could make it to the train station in Irpin, a village outside of Kyiv that we had fled to after the war began. Nearly as soon as we pulled away from the rural farmhouse where we were staying, we ran into Russian armoured vehicles.

“Go back, go back!” my wife screamed. The driver frantically tried to reverse. It was too late. Russian infantrymen began spraying our Toyota Camry with automatic weapons fire and chasing after us. As I ducked behind the driver’s seat, I could hear the glass shattering into a million pieces as the bullets struck the windows.

Somehow we managed to jump out of the moving car, hop over a fence and take cover behind a bright blue port-a-potty. Our bullet-riddled Camry careened down an incline and smashed into a fence. It was a complete wreck.

“Come out from behind there!” yelled a Russian soldier. We stepped out from our hiding place, hands raised, explaining we were unarmed civilians on our way to a train station. The Russian soldiers approached and pointed rifles in our faces.

The story of our capture started with a miscalculation. “There will not be a war.” I heard that phrase over and over in Kyiv. My wife, Iryna Samsonenko, and I had been living in Ukraine for 21 years. I worked as a military affairs and Russian political analyst, and as a consultant to the aerospace industry. Putin threatening Ukraine was a movie we had seen many times, and I assumed the saber rattling was just that and nothing more.

Then the missile strikes began. Around four in the morning the air-raid sirens sounded, and we sought shelter in the underground garage across the street from where we lived in Kyiv.

When the shelling stopped later that day, we returned home. A few hours later, the bombardment began anew. We did not know what to do. Getting in our car and driving west—away from the Russians—was impossible. The roads were clogged with traffic for miles, and there was not a drop of gas to be had anywhere from Kyiv to the Polish border. Anyone left in the city was now trapped there.

Adding to the sense of helplessness was the odour of exploded ordnance permeating the air. This was not just a campaign against Ukraine’s armed forces; this was a war to terrorize the civilian population.

After spending two nights in air-raid shelters, we decided to evacuate. We had friends about an hour outside the city, and they kindly agreed to let us stay in their guesthouse.

Within two days of arriving, the fighting in and around nearby Gostomel Airport had shut down all utilities. The artillery and mortar duels between Ukrainian and Russian forces destroyed the water and power lines. Reaching their house was not so difficult, but now going back to Kyiv was impossible—every bridge between us and the city had been blown up to stall the Russian advance. In our attempt to reach safety, we had become trapped. There was no exit from this place, as the entire area was now ringed with Russian troops and armour.

During this time, our son, Antonio Brasileiro Johnson, 18, was at his boarding school in Cambridge, England, monitoring the war 24/7. He spent long nights speaking with people in Ukraine, in some cases helping them find air-raid shelters and ways to get out of battle zones, but he had only limited contact with us. No electricity except for about three hours a day from a gas generator meant smartphones were almost impossible to recharge. So Wednesday, 2 March, was the last time we were able to talk to Antonio.

The next day, I had expended most of the battery remaining on my MacBook Pro to compose an article on the war. At one point I had to stop working and all of us—Iryna and I, our friends and their children, housekeeper and nanny—had to take shelter in their root cellar while several Russian armoured vehicles were stopped on the road outside the house. The Russians appeared to be lost in the maze of country roads.

They eventually moved on, but it was clearly no longer safe to stay here. So we made a break back to Kyiv—and fell into the hands of the Russian army.

WE WATCHED IN horror as the Russians looted our car—our belongings violently ransacked and everything of value smashed or stolen. Iryna had a hard drive full of nothing but family pictures, and photos and videos of our son playing piano. It was among the many items stolen. A lifetime of memories gone in an instant.

I noticed blood running down Iryna’s face. Flying fragments of glass from the shattered windows had lacerated her left cheek, and there were small grains of glass in her eye. Fortunately a Russian combat medic was on the scene and treated her before the condition could become worse.

All our computers and other hard drives were taken. All the work, every article I had ever written, every document I had ever saved, every photograph I had ever taken were all gone.

But the big bonanza for these war criminals was yet to come. As they tore into my computer bag, they found the portfolio where I was keeping the money we had saved for my son’s education. “Foreign currency!” exclaimed one gleefully. This to them was the best payday they were ever going to see.

The soldiers next began rifling through a pile of research materials I was using for some writing I was doing on the history of missile systems. Though none of the documents was classified, these dimwits were convinced that they had stumbled across some top-level intelligence operative. The same soldier was so overjoyed at the prospect of stealing all our money that he put a grenade in the pocket of my coat and threatened to pull the pin if I did not tell him which secret agency I must be working for.

Once they had finished stealing everything we owned, we were sent into a dark basement in a nearby building where numerous civilians were being held. Why these people had been detained was unclear, but I would be shocked if any of them were still alive today. Groups of people who were held in this area ended up in mass graves.

Next we were packed into an armoured vehicle. Two Ukrainian civilians with their hands tied behind their backs were thrown in on top of our legs. We travelled this way for an hour and a half. While in transit, one of the Russian soldiers stole a gold ring that I had owned for 25 years. I had planned to give it to Antonio once he graduated from college.

At some point we stopped in the middle of a forest. The two Ukrainians thrown in on top of us were tossed out onto the freezing cold mud.

I never saw what happened to them, but I fear the worst.

Iryna and I were told to stand, not sit, in one place, with temperatures dropping precipitously. Were we going to be taken into the woods and shot? We stood this way for two hours, face to face, keeping our hands warm by holding on to each other. Some soldiers took pity on us and gave us half-full cups of hot tea.

Finally, after some questioning about my papers, the soldiers left us in a van overnight with a box of the Russian equivalent of C rations and some water. The driver came in periodically to run the engine for 10 minutes or so to warm up the interior and then shut it down again. We tried to sleep, but without knowing what the next day would bring, sleep was not possible.

The next morning, we were driven down roads strewn with burnt-out military and civilian vehicles. The back half of rockets protruded out of the ground—unexploded duds—and signs of explosions and devastation were everywhere. It was a journey through the landscape of hell.

Then we saw our destination: Gostomel Airport. The runways were cratered and no longer serviceable, and the Russian army was using Gostomel as a command post of sorts. We were blindfolded and taken to an underground bunker, and when the blindfolds were removed, we were in a small room with a wooden desk, three cheap chairs and nothing else.

The floor was filthy; the air cold, wet. There was no clock to tell the time and no calendar to know the date. Iryna began keeping track of the days Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo–style, by making six vertical lines and then a seventh horizontal line at an angle on the wall. How long we would be in this place was impossible to determine. No one told us why we were there or under what auspices we were held.

No one in the outside world knew where we were, or if we were still alive. All we knew was that each morning when the radios and phones in the room across the corridor began ringing, it was the beginning of another day of war.

BACK IN CAMBRIDGE, Antonio knew something was wrong. It was now Sunday, and he had not heard from us since Wednesday. He finally managed to get a call through to our friends whose place we had been staying at, and they told him the horrifying news, which they’d learnt from the driver we had hired.

My son went straight to work trying to save us. Even at age 18, he knew how US government bureaucracy worked. His first call was to the American Embassy in London. Trying not to panic, he explained that he needed to come to the embassy to speak to someone about his parents. “Make an appointment,” he was told.

His next step was to call a friend of ours, retired US Air Force Maj. Gen. John Schoeppner Jr. He is a fighter pilot’s fighter pilot who flew 154 combat missions over Vietnam and was the commander of Edwards Air Force Base.

When Antonio relayed the situation, Schoeppner’s general’s stars began flashing. He picked up the phone and called the American Embassy in London in what I was told was “an exercise in focussing their attention.”

His intervention worked. Within minutes, Antonio received a call back from someone farther up the food chain in the London embassy, who then relayed him to the American Embassy in Moscow. The State Department then put our situation in the hands of some very focussed people.

In the meantime, Schoeppner was on the phone to those he knew in the Pentagon, raising an equal level of attention with people there.

After these initial interactions, Antonio was in contact with people from almost every government entity in the US, United Kingdom and Ukraine that you could think of. In Kyiv they were beginning to put together a rescue plan that would involve Ukrainian special-ops troops storming the airport.

But we knew none of this.

TO SAY IRYNA and I were in an information vacuum is being generous. All we knew was that there would be no quick end to this war.

We were held in a windowless underground room guarded by a soldier with an AK-47 cradled on his lap all hours of the day. There was no possible escape—not even MacGyver could have found a way out.

We slept on a flimsy wafer-thin mattress large enough for only one person, and we had only a single blanket against the clammy cold of early March. My folded-up overcoat served as our pillow.

Sanitary conditions were non-existent. I had to urinate into an empty plastic water bottle. Defecating was done into a bucket in the corner of the room that thankfully had a lid to suppress the foul smell. We were provided Russian army C rations but did not consume much. Living in this modern-day dungeon caused considerable stress. I suffer from hypertension and could tell that my blood pressure was dangerously high.

Our captors did everything they could to hide what was going on in the other sections of the bunker, but we could hear everything. The room next to ours was a medical triage unit. The sounds of the maimed and dying still haunt me. Russian soldiers screaming from their wounds. Others babbling incoherently, slipping in and out of consciousness as the morphine could only partially kill their pain.

Then there was the sound of a big, wide roll of packing tape being dispensed and wound around something. We knew what this sound was: Tape is used to bind the ankles of dead soldiers inside body bags.

Every day we were under bombardment. The Ukrainian forces were never far away, and by conducting ‘shoot and scoot’ harassment attacks against the airport, they made it impossible for the Russians to repair the runways. The building shook from the proximity of the sustained blasts. Even in the middle of the night, an artillery or mortar duel was not uncommon. We began to worry when the bombardments were accompanied by the sound of small-arms fire, signs the fighting was almost on top of us.

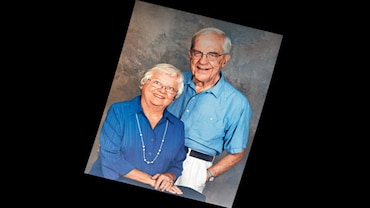

Reuben (centre) with Iryna and Antonio in more carefree days before the war. Credit: Viktor Kovalevsky

EIGHT DAYS AFTER we were captured, Antonio was contacted by a Ukrainian-émigré colleague I knew in Kyiv. She had been a translator and an analyst for high-level US military officials interacting with Ukraine, and she had her own connections to the Pentagon. We still had no idea that any of this was taking place, but there were ultimately several people working on our release.

One was Charlie Mount, who runs a catamaran charter-cruise service in Florida. He met with one of his friends, who phoned someone. He never told Charlie who it was, but when he put the phone down, he said, “Something is in motion. Don’t ask me what, but things are happening.”

Two days later, two soldiers appeared in our room and told us we were leaving. We were again blindfolded, then brought to the surface for the first time in 10 days. Supposedly we were going to be taken from the airport to another location, but when we were halfway between the bunker and the truck to transport us, the airport was hit with a mortar attack. Our escorts scampered for cover and left us out in the open, blindfolded, exposed to furious shelling. How we managed to avoid being hit I do not know, but when the firing subsided, our escorts shoved us into a truck.

We were taken to a nearby village and put into a small building being used by the Russians as a command post. Inside, they stuck us in a shower room with the showerheads removed, almost like in the movies about Nazi death camps during World War II. We were fed a small hot meal—the first one in two weeks—and then told we had to sleep sitting up on cold metal chairs.

The next morning, 15 March, we were driven toward the north. The road was littered with cars shot to pieces. There were burnt-out military vehicles, endless signs of explosions and the tracks of heavy vehicles that had chewed up the road.

Several hours later, we were dropped in the middle of nowhere. Our driver gave us back our passports and said, “Back the way you came is Ukraine, and that way is Belarus.” Pointing toward Belarus, he said, “You should start walking.” We could see nothing but empty fields and forests off in the distance. It was 5 p.m. and less than two hours from nightfall, so we started walking.

We finally reached a Belarus border checkpoint and explained that we were refugees. They let us cross after a series of questions from their immigration, customs and security personnel. Then came the greatest moment of our lives. A Red Cross worker had a tablet, and we were able to call Antonio on Telegram, an instant messaging app, and tell him we were alive. I was never so happy to hear my son’s voice.

The next day we boarded a night train that took us to the Polish border at Brest. Several hours later, we were in Warsaw. First Iryna, and then I, some days later, flew to the US. The following month, Antonio flew from London to join us. We were reunited.

“Welcome home, Papa,” he said as I hugged him, my body shaking with emotion. “I will always be here waiting for you.”

This article was originally published in Rolling Stone (19 November 2022), © 2022 Rolling Stone, LLC. All rights reserved.