- HOME

- /

- True Stories

- /

"I Never Forgot You": An 83-Year-Old Man Reunites With His First Love

After more than six decades, a doomed teenage romance gets a second chance

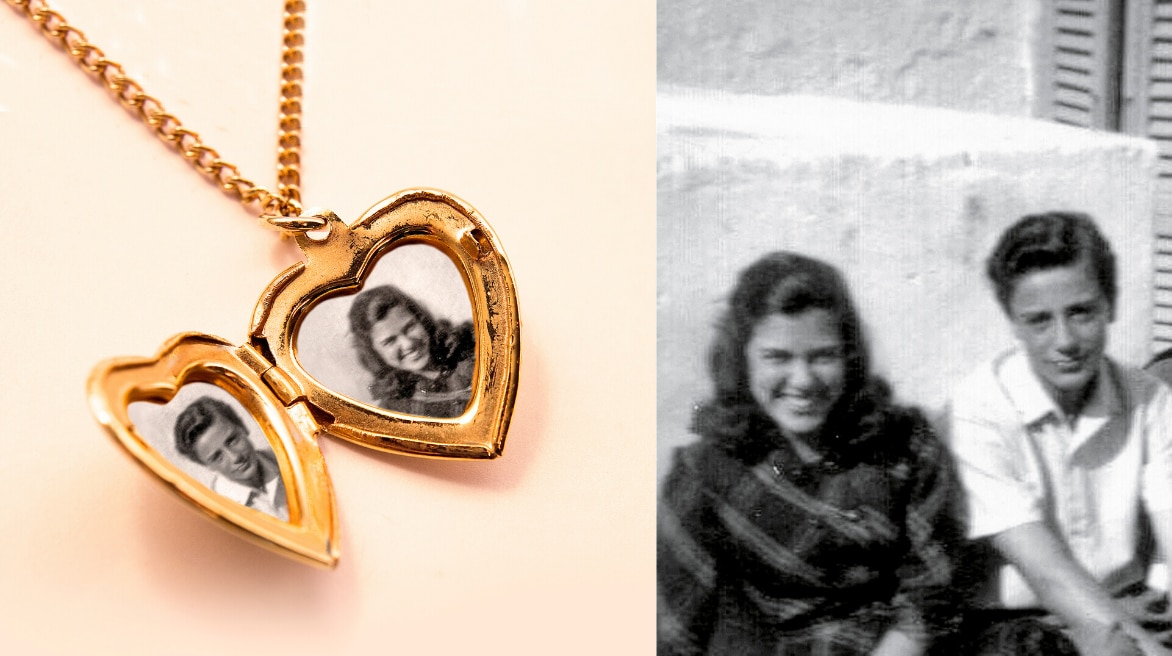

Marilena and Aldo in Polignano a Mare. “I thank God for allowing me the chance to be with you,” he wrote to her. (Photo courtesy of the author)

Marilena and Aldo in Polignano a Mare. “I thank God for allowing me the chance to be with you,” he wrote to her. (Photo courtesy of the author)

On a sunny Saturday in April 2017, the phone rang in my grandmother’s house in São Carlos, Brazil. “I’ve been looking for you for decades,” the man on the line whispered in Italian. “You were my first love.”

It had been more than six decades since my grandmother had heard the voice of Aldo Sportelli, now 83.

She pictured his youthful face and wondered what he looked like now. Aldo’s voice trembled as he recalled the last time he saw her in southern Italy. He had spent years tracking her down.

For 10 minutes they caught each other up on how their lives had unfolded—both married for half a century, my grandmother widowed, Aldo’s wife in the last stages of Alzheimer’s, kids, grandkids, careers.

“You just don’t think this type of thing will ever happen to you,” my grandmother told me.

***

In 1951, when my grandmother, Marilena, was 14, she set off on a year-long trip to Italy with her grandparents. Her grandfather, Antonio Lerario, was the son of an illiterate fisherman who, in 1885, at the age of 14, had left Italy for Brazil as a stowaway. He joined thousands of Italian immigrants in São Paulo, where he sold bags of rice on the street. He eventually saved enough money to open his own warehouse and went on to create a multimillion-dollar cereal empire.

After World War II, he decided to return to Italy and invited Marilena, his eldest granddaughter, to come along. In April 1951, the SS Conte Biancamano, an Italian ocean liner, departed the Brazilian port of Santos. My grandmother was the youngest passenger in first class, which included counts, members of the Brazilian aristocracy and the archbishop of Rio de Janeiro.

After the ship docked in Genoa, Marilena and her grandparents took a train to Puglia, the heel of the boot. The war had been over for six years, but destruction lingered. The rubble, though, could not dampen the bleached beauty of Polignano a Mare, her grandfather’s hometown. The village is perched on limestone cliffs on the edge of the sea. As a returning rice tycoon, Antonio would stay with his family in the Hotel Sportelli.

The hotel was three stories, with a terrace facing the sea. Underneath, scooped into a cliff, was a vast cave that held the Grotta Palazzese luxury restaurant. Visitors from around the world came to dine.

Marilena, who spent her days people-watching from the hotel terrace, was never allowed into the cave. After catching some businessmen ogling her from the restaurant, her grandmother started shooing her to the kitchen as soon as the lunch-rush began. Svelte, with a tiny waist, she exuded the kind of aloof, effortless glamour of a Hollywood movie star. Dark curls framed her face. She had heart-shaped lips, a dainty nose and a curious smile.

While making herself useful in the kitchen, Marilena picked up Italian and got to know the Sportelli family. Aldo Sportelli, one year her senior, was smitten. Lanky, with a shy smile, he would hang around the kitchen when he came home from school. “It was my first infatuation,” Aldo would tell me. They spoke about their plans for the future. He wanted to become an engineer. She had no idea what awaited her when she returned to Brazil.

After school, Aldo served the glamorous patrons in the restaurant; my grandmother spent her nights listening to the music from the cave below. Every now and then, Aldo joined her on the terrace, always under the watchful eye of a family member.

One day, as Marilena was going down the stairs to the kitchen, Aldo went in for a hug. Unsure of what to do, she rushed away.

My grandmother’s family was not happy with the budding romance. The son of a hotel owner was not what they had in mind for the family heiress. Aldo’s mother told him the social distances between him and Marilena were too large to bridge. “At that time, I thought they were right,” Aldo recalls.

The two continued an awkward but friendly relationship over her last few weeks at the hotel. Before she left, she asked him to sign her memory book. “Marilena, if you allow it, a friendship can be an enduring bond,” he wrote.

When she left, he went to the station and watched as the train pulled away. It was one of the saddest moments of his life, Aldo says.

Marilena Lerario and Aldo Sportelli met in Polignano a Mare, her grandfather’s hometown, when she spent a year in Italy in 1951. (Photo courtesy of the author)

Marilena Lerario and Aldo Sportelli met in Polignano a Mare, her grandfather’s hometown, when she spent a year in Italy in 1951. (Photo courtesy of the author)

***

My grandmother met my grandfather in college, and by 1969, she was married with four children. Her marriage was happy, but my grandfather’s jealousy contained her curiosity about the world. When they ate at restaurants, she faced the back to avoid other patrons’ wandering eyes.

Shortly after the wedding, they moved three hours away from São Paulo to a town in southern Brazil. My grandfather enjoyed small-town life, but my grandmother struggled to adjust. After he died, she started spending half the year with my mother in Miami.

Meanwhile, Aldo studied engineering. For most of his career, he worked on urban planning for local communities. In 1959 he met Beatrice at a party. They married and had two children.

Beatrice suffered from depression, and the marriage was hard on Aldo. Their circle of friends was small, and they rarely travelled. After his mother died in 1995, he came across a wedding photo of his beloved Marilena among her letters. Her grandmother must have sent it.

“I thought, ‘Where is she? How is her life?’” he recalls. “The thought that I would never again hear from the girl who captured my boyhood heart tormented me.” And so began his search.

Aldo tried to reach the wedding photographer, but he was long dead. He emailed the mayor’s office of São Paulo, asking for information on a Marilena Lerario. “We’re a city of 12 million people,” Aldo was told. “We can’t help you.”

In 2012, Beatrice was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. She eventually stopped speaking and barely recognized her children. She refused at-home care from nurses and relied on Aldo for her every need.

Finally, two decades after he started his search, Aldo contacted the daughter of a family friend who worked at the Brazilian tax authority. She found Marilena, and passed him her phone number.

When Aldo phoned that afternoon, he told Marilena, “I never forgot you.” My grandmother was speechless.

***

The next day, Aldo called again. What did her children do? he asked. What were her days like?

“I don’t even know what he looks like, and we talk every day,” my grandmother said to me.

“Let’s look him up on Facebook,” I suggested.

I pulled up Aldo’s photo. He had white hair but the same sad eyes and shy smile he had at 17. “He’s handsome,” my grandmother said.

I suggested they communicate by video chat. The following weekend I went to her house for a family get-together and messaged Aldo to arrange the call. My family was eager to see the man my grandmother wouldn’t stop talking about.

There was Aldo on the computer screen, beaming. “You didn’t use to be blonde!” he said. My grandmother burst into giggles.

Week after week, Aldo kept calling. “It is nice to have someone care about me again,” my grandmother told me.

The messages soon grew rosier: heart emojis and photos of flowers. “For when you wake up: Good morning,” he messaged once, when it was daytime in Italy but still dark in Brazil.

My grandmother, who had shut herself off from the world, came back to life. She began dressing up for their virtual dates, putting on lipstick and fixing her hair.

“We have to take you back to Polignano!” my mother said one day. My grandmother rejected the idea, saying, “He has a wife!”

My mother was persistent, and soon Marilena called Aldo with the news. “We’ll be there for two weeks in September,” she said. He agreed she should come.

Accompanied by my mother, my dad, my aunt, two cousins and me, my grandmother landed in Bari, nervous but smiling. When we arrived at the hotel in Polignano, a bouquet of pink roses was waiting for her. “Welcome to your hometown,” Aldo had written on the card. “I hope you don’t wait another 68 years to return.”

The next morning we drove past miles of twisted olive groves. My grandmother sighed and said, “It’s interesting, isn’t it? An old lady, seeing an old man.”

Aldo had asked us to meet him at the church of San Vito, where Mass would soon be starting. When we pulled up to the entrance, he was waiting. With sky-blue eyes hiding behind silver Ray-Ban sunglasses, slicked-back hair and a tan jacket, he was as cool an octogenarian as I’ve seen.

My grandmother leapt out of the car and walked toward him, her arms open.

“So beautiful,” he said, trembling as he hugged her. She blushed and introduced him to the family. “It’s a historic moment, a miracle,” he announced.

Later, my grandmother handed Aldo two gifts. One was a new iPhone— his was old and always cutting out during their conversations. “And this is for Beatrice,” she said, pointing to the second gift. He opened it to find a grey shawl. Aldo stared at my grandmother, tearing up and mouthing, “Thank you.”

We asked him out for lunch, but he said he had to go home and relieve the housekeeper who was watching his wife. Aldo sent my grandmother a message late that night. “There we were, you and I, as if we had been good friends for 68 years, helping each other in sorrow and rejoicing together in joy,” he wrote. “I thank God for allowing me the chance to be with you.”

Lerario and Sportelli when they met in 1951 (Photos coutesy of the author, Shutterstock)

Lerario and Sportelli when they met in 1951 (Photos coutesy of the author, Shutterstock)

***

They met for coffee daily, during the few hours he could get out of the house. My grandmother refused to be alone with him. “What would people think if they saw us together?” she said. “It looks bad.”

At first I laughed this off as an antiquated sense of modesty. But everywhere we went Aldo seemed to run into an acquaintance. “Aldo Sportelli!” a friend would shout from across the street, making my grandmother cringe.

On one date he brought his daughter and grandson. I was worried about what they would think of my grandmother, but all anxiety disappeared when we met them. Sabrina, Aldo’s daughter, pulled my grandmother into a tight hug. My grandmother had brought her a necklace, which she put on right away. “Give Grandma Marilena a hug,” Sabrina told Giorgio, her 12-year-old son.

“It’s been a gift for Dad,” Sabrina said later that day when I asked how she felt about their relationship. “He’s a victim of Mother’s condition.”

When we weren’t with Aldo and his family, my grandmother wanted to explore Polignano. It was still a charming hamlet with narrow limestone streets leading to scenic outposts overlooking the sea. But much had changed since her last visit. Red Bull had chosen Polignano as the site for its annual cliff-diving competition, and the town was now overrun with tourists.

The restaurant in the cave was still operating, and my grandmother, who was allowed to watch guests dine there only from a distance at 15, wanted to see it up close. On one of our last nights in Polignano, we descended the 60 steps into the cave for dinner.

When we emerged onto the wooden deck, the view took my breath away. We were suspended some 30 feet above the sea. The emerald water’s reflection danced against the limestone dome of the cave.

Aldo had refused to come because the memories of losing the nearby Hotel Sportelli in a financial dispute 20 years ago were too painful. My grandmother respected his decision.

“Isn’t it amazing?” she said, gazing out at the sea. “Only nature knows how many millions of years this has been here.”

The next day, at another coffee shop, Aldo pulled out a family photo from 1934, and my grandmother studied it. “I met every one of them,” she said. “We’ve had this shared life together. Isn’t that crazy?”

Aldo caught her up on what happened to each person in the photo.

“When do you leave?” he asked.

“Tomorrow,” she said.

They still had 40 minutes before Aldo had to head home. After chaperoning every moment they spent together, I left my grandmother alone to enjoy the last moments of her last date.

***

The next morning, Aldo, Sabrina and Giorgio met us at the hotel. We thanked them for their hospitality and for making my grandmother so happy. “Our family will be an extension of yours,” my dad said.

I was surprised to see tears running down Sabrina’s face. “Take care of him,” my grandmother said, hugging her. She nodded, sobbing.

Aldo took my grandmother’s hand in his. “Now, I will do the hardest thing: Turn around and walk away,” he said.

My grandmother didn’t allow herself to indulge in the finality of the moment. She gave Aldo one last hug, and, as we walked away, she held up her phone and said: “I’ll see you tomorrow.”

Aldo and Marilena continue to speak daily. Marilena had said that she may visit Italy later this year, if she is in good health. Aldo’s wife is still alive but her health continues to decline. Aldo has told Marilena that he believed her to be the love of his life when they first met and that their reuniting was “a blessing from God.”