He Cured His Own Disease

A medical student battling a deadly disorder finally got a lifeline—from his own research.

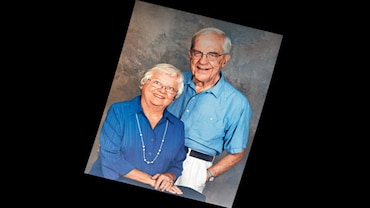

David Fajgenbaum with his wife and daughter (left), and in his office; Image Courtesy Rachel utain-evans/rachelutainevans.com (left). Peter Murray (right)

David Fajgenbaum with his wife and daughter (left), and in his office; Image Courtesy Rachel utain-evans/rachelutainevans.com (left). Peter Murray (right)

It was just after Christmas 2013, and David Fajgenbaum was hovering a hair above death. He lay in a hospital bed at the University of Arkansas, his blood platelet count so low that even a slight bump to his body could trigger a lethal brain bleed. A doctor told him to write his living will on a piece of paper.

David was rushed to a CT scan. Tears streamed down his face and fell on his hospital gown. He thought about the first patient who’d died under his care in medical school and how her brain had bled in a similar way from a stroke. He didn’t believe he’d survive the scan. But he did.

David was battling Castleman disease, a rare autoimmune disorder involving immune cells attacking vital organs. It wasn’t the first time a relapse had threatened his life. Massive ‘shock and awe’ chemotherapy regimens had helped him narrowly escape death during four previous attacks, but each new assault on his body weakened him.

“You learn a lot by almost dying,” he says. He learnt enough to surprise his doctors by coming up with a way to treat his disease. Six years later, he’s in remission, he and his wife have a baby girl, and he’s devoting his medical career to saving other patients like him.

As a boy in Raleigh, North Carolina, David spent Saturdays watching the North Carolina State Wolfpack football team with his dad, the team’s doctor. At age seven, he was obsessed with becoming a Division-I athlete. In middle school, he would wake up at 5 a.m. to go running. The walls of his bedroom were covered with football play charts.

He achieved his dream, making the Georgetown University football team as a quarterback. But in 2004, during his sophomore year, his mother died of a brain tumour. His obsessive focus deepened, helping him learn to appreciate life’s precious moments and understand that bad things happen to good people. “I know people far more worthy of miracles than I am who haven’t gotten them,” he says. David founded a support group for grieving college students at Georgetown called Students of AMF—an acronym for Ailing Mothers and Fathers, as well as his mother’s initials.

David went on to earn a master’s degree at the University of Oxford, where he learned how to conduct scientific research so that he could fight the disease that took his mom. That relentless focus and scientific rigour would one day save his life.David entered medical school at the University of Pennsylvania to become a doctor like his father—specifically, an oncologist, in tribute to his late mother.

In 2010, during his third year, he got very sick and was hospitalized for five months. Something was attacking his liver, kidneys and other organs and shutting them down.

David Fajgenbaum’s football body fell victim to organ failure associated with Castleman disease (right).

David Fajgenbaum’s football body fell victim to organ failure associated with Castleman disease (right).

The diagnosis was idiopathic multi-centric Castleman disease. First described in 1954, Castleman presents partly like an autoimmune condition and partly like cancer. It’s about as rare as ALS; there are around 7,000 new cases each year in the United States. The disease causes certain immune-signalling molecules, called cytokines, to go into overdrive. It’s as if they’re calling in fighter jets for all-out attacks on home territory.

In his hospital bed, David felt nauseated and weak. His organs were failing, and he noticed curious red spots on his skin. He asked each new doctor who came in his room what the ‘blood moles’ meant. But his doctors, focussed on saving his life, weren’t interested in them. “They went out of their way to say they didn’t matter,” David says. But the med student turned patient would prove he was on to something. “Patients pick up on things no one else sees,” he says.

Castleman disease struck David four more times over the next three years, with hospitalizations that ranged from weeks to months. He stayed alive only through intense chemotherapy ‘carpet bombing’ campaigns. During one relapse at a Duke University hospital, his family called in a priest to give him his last rites.

After all the setbacks, all the organ failure, all the chemo, David worried that his body would simply break. Yet despite it all, he managed to graduate from medical school. He also founded the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN), a global initiative devoted to fighting Castleman disease.

Through the CDCN, he began bringing the world’s top Castleman disease researchers together for meetings in the same room. His group worked with doctors and researchers as well as patients to prioritize the studies that needed to be done soonest.Rather than hoping for the right researchers to apply for grants, they recruited the best researchers to investigate Castleman.David also prioritized clinical trials that repurposed drugs the FDA had already approved as safe rather than starting from scratch with new compounds.

Meanwhile, he never knew whether the next recurrence would finally kill him. Staving off relapses meant flying to North Carolina every three weeks to receive chemotherapy treatments. Even so, he proposed to his college sweetheart, handing her a letter written by his niece that said, in part, “I’m a really good flower girl.”

“The disease wasn’t a hindrance to me,” says his now-wife, Caitlin Fajgenbaum. “I just wanted to be together.” But in late 2013, Castleman struck again, landing David in that Arkansas hospital. It marked his closest brush with death yet. Before he and Caitlin could send out their save-the-date postcards, David set out to try to save his own life.

After examining his medical charts, he zeroed in on an idea that—more than 60 years after Castleman disease was discovered—researchers hadn’t yet explored. A protein called vascular endothelial growth factor, or VEGF, was spiking at 10 times its normal level. David had learnt in medical school that VEGF controls blood vessel growth, and he hypothesized that the blood moles that had shown up with every Castleman relapse were a direct result of that protein spike, which signals the immune system to take action.

He also knew that there was an immuno-suppressant called sirolimus that was approved by the FDA to help fight the immune system when it activated against kidney transplants. After consulting with a National Institutes of Health expert, David asked his doctor to prescribe the drug. He picked it up in February 2014 at a pharmacy less than a mile from his home. “A drug that could potentially save my life was hiding in plain sight,” he says.

So far, it’s working. David has been in remission from Castleman for more than six years. He’s not the muscular football player he once was, but he’s close to full strength. He is now an assistant medical professor at the University of Pennsylvania, running a research lab and enrolling patients in a clinical trial for the drug that has given him his life back.

In 2018, he and Caitlin became parents when their daughter, Amelia, was born. “She’s such a little miracle,” Caitlin says. “We’re so lucky to have her.” David hopes his story offers lessons far beyond medicine about what people can do when they’re backed against a wall. And he feels his suffering means something when he looks in the eyes of his patients with Castleman disease. One girl, named Katie, was diagnosed at age two and endured 14 hospitalizations.

Then her doctor prescribed David’s drug after the family reached out to the CDCN. Katie hasn’t been hospitalized since and just finished kindergarten. She has even learnt how to ride a bike.

CNN.com (16 September 2019), Copyright © 2019 by Turner Broadcasting Systems, Inc., cnn.com.