Echoes of the Past

A visit to the ancient Barabar caves in Bihar reveals a surprising connection to a literary classic

The entrance to the Lomas Rishi at Barabar. The metal trolley-style gate is a modern-day addition to prevent unauthorized entry and vandalism. Photo: Shutterstock

The entrance to the Lomas Rishi at Barabar. The metal trolley-style gate is a modern-day addition to prevent unauthorized entry and vandalism. Photo: Shutterstock

Fiction can, in our imagination, create a stronger impress of actuality than tangible reality itself. And, consequently, we may find it difficult to tell one from the other. Such is the case of the Marabar Caves. It’s obvious from the very first sentence that the Marabar Caves were the focal point of A Passage to India, the novel on the muddle of race relations that E. M. Forster had written exactly one hundred years ago. They resonate through the narrative, the conversations and thought processes of its characters like the echoes that rebound within the caves’ dark, cavernous interiors. It is an acoustic reality that booms through the novel.

It wasn’t until months after my visit to Bihar last December that I discovered that even friends who taught English literature in universities had no idea that the impulse behind those fictional Marabar Caves came from a network of caves known as Barabar in what once were the badlands of the Makhdumpur region in the state’s Jehanabad district—a territory where banditry and Naxalite insurgents had a free run. I too didn’t know the Barabar Caves even existed.

It was close to Christmas, and so, expecting the dreaded Bihar cold wave, we—my young nephew Somnath was my travelling companion—had armed ourselves with the heaviest jackets and thermals. It turned out to be quite otherwise, however, and I was forced to peel off all my coverings.

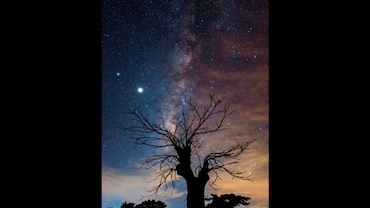

Bihar upended all our expectations. The rough-hewn, untrammeled beauty of nature—low-lying hills leaning against the horizon, miles of rolling grassland with palm trees standing sentinel, and acres of cultivated land—adequately compensated for the occasional rough patches on the roadways. Boulders both small and gigantic were strewn all along.

At Kolhua, 65 kms north-west of Patna, people were out in droves milling around the ancient water tanks, stupa and parks enjoying the sun. The enchanting Didarganj Yakshi statue with its luminous sandstone epidermis in Bihar Museum had cast her spell on me. We had already visited Vaishali Stupa at the excavation site in Kolhua where a gleaming red sandstone life-size sculpture of a lion couchant is installed atop an Asokan pillar.

The Lomas Rishi Cave, also known as the Grotto of Lomas Rishi, unlike the other three caves in the group, has no Ashoka inscriptions. This is perhaps due to the reason that the cave was never completed due to structural rock side problems. Photo: Courtesy of Soumitra Das

The Lomas Rishi Cave, also known as the Grotto of Lomas Rishi, unlike the other three caves in the group, has no Ashoka inscriptions. This is perhaps due to the reason that the cave was never completed due to structural rock side problems. Photo: Courtesy of Soumitra Das

After leaving Gaya city behind late morning, we were on our way to Bodh Gaya, where we were to stay overnight. But, midway, the driver suddenly declared we would stop at the Barabar Caves.

"Barabar Caves? Where could that be?" The driver kept mum. So I invoked Google. Sure enough, the Barabar Caves are very real. Wikipedia added: “The caves were featured—located in fictitious Marabar—in the book A Passage to India by English E. M. Forster.” I am circumspect about information available online. But I had noticed the eatery with ‘Barabar Jalpan Griha’ emblazoned on it near the parking lot.

The trek to the Barabar Caves is no uphill task. Flat and wide stone steps lead up to the caves. The rugged Barabar granite hills encircling the steps are densely forested. The ancient trees and massive boulders on the right side of the pathway are like a protective wall. A guard rail runs all along on the left. But was it really possible for an elephant to carry Mrs Moore, Adela Quested and Dr Aziz—the protagonists of Forster’s story—to the Marabar Caves as described in the novel?

Forster wasn’t writing a travel vlog and had no obligation to stick to facts. There was no signage in sight. We did, however, encounter a battered board on which was written in fading Devanagari: ‘Barabar Sopan’, the latter meaning ‘steps’.

There is nothing there to indicate that the Barabar Caves are the oldest extant rock-cut caves in India, and are the precursors of the larger Buddhist Chaityas of Maharashtra, the most famous of which are the Ajanta and Karla Caves. The Barabar Caves go back to the Mauryan Empire, and the walls bear Asokan inscriptions.

At the end of the stairway, the ground plateaus, and on its left is a giant hump of monolithic granite. Its lower reaches had been scooped out to form the famous caves. On the flat ground was a bench shared by both tourists and devotees, who had trekked to the Barabar peak to worship Shiva.

Forster had described the Marabar Hills as “fists and fingers … containing the extraordinary caves.” But neither the 1968 BBC play based on Santha Rama Rau’s acclaimed adaptation of the novel nor David Lean’s film was shot here. The knowledgeable Dr Shanker Sharma, then the Assistant Superintending Archaeologist, Archaeological Survey of India, Nalanda, who we met at the vast and magnificent ruins of the ancient university of Nalanda in the eponymous district, told me there are four caves in the Barabar hills—Karan Chaupar, Sudama, Lomas Rishi, Viswa Jhopa or Viswamitra or Vishwakarma. The oldest of these caves belong to the Maurya period—3rd to 2nd century BCE—while the subsequent ones belong to the later Gupta period of 6th to 7th century CE.

On the walls of the Caves are dedicatory inscriptions in Brahmi script, and in Pali and Sanskrit languages. These have been deciphered. The caves were gifts of the Maurya king Asoka and of his grandson, Dasrath, to the Ajivikas, an ascetic sect that was a contemporary of Buddhism and Jainism and which existed till the 14th century. In the Barabar Caves it is inscribed on the walls that in his 12th Regnal year, Priyadasi or Asoka had, after his consecration made the gift of the Caves to the Ajivikas, for protecting them was his dharma.

Next to the Karan Chaupar, a flight of steps was hewn out of the granite monolith and on its right was a sculpture panel that resembled a giant termite mound. Some of the visitors said the caves were locked and a watchman had the keys. Thankfully, he seemed to appear from nowhere, and he opened the padlock hanging from the grated rectangular entrance.

Inside, the barrel-vaulted caves are pitch dark, but the moment a match is struck, the mirror-like skin of the walls come alive and the flame dances on the smooth, gleaming surface. Forster had described it in poetic terms: “There is little to see, and no eye to see it, until the visitor arrives for his five minutes, and strikes a match. Immediately another flame rises in the depths of the rock and moves towards the surface like an imprisoned spirit: the walls of the circular chamber have been most marvelously polished.” This is the ‘Mauryan polish’ that the Didarganj Yakshi and the Vaishali lion column also boast.

The Karan Chaupar caves, located on the northern side of the Barabar hills were reserved for Buddhist monks. Photo: Soumitra Das

The Karan Chaupar caves, located on the northern side of the Barabar hills were reserved for Buddhist monks. Photo: Soumitra Das

As we entered a cave, someone switched on his mobile phone torchlight, and immediately the shimmering walls emerged from the darkness. It had an eerie glow as if we were underwater. Coupled with the echo that kept resounding and reverberating—any sound made in these caves lasts 3 minutes—the unearthly light can have an unnerving and even a disorientating effect, particularly on those with a suggestible imagination like Mrs Moore and Adela Quested.

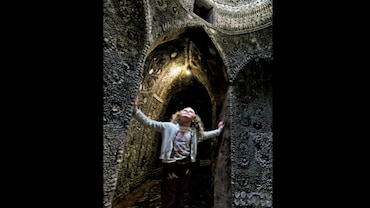

Next, we headed to the Lomas Rishi Cave. Widely believed to be the first cave in which architectural elements have been introduced, Dr Sharma says, “The doorway of this cave is exactly of the same size as that of the Sudama Cave, but the entrance porch has been much enlarged, and has been sculptured to represent the ornamental entrance of a wooden building.”

The sculptured entrance is the first example of the ogee shaped chaitya arch—an important element of rock-cut architecture. An elegant procession of elephants carved into the rock traces the outline of the portal arch. There are paintings with red ochre inside both Lomas Rishi and Sudama Caves but they have faded with age. Before its iron doors were installed, merrymakers and devotees would burst firecrackers inside the Caves. The boom turned on the vandals. The lustrous polished walls are therefore pitted and peeling. The damage is irreversible.

Harsh climatic conditions and moisture have worsened the condition of the Caves, which need proper conservation and protection from the elements. Since the Caves are under the Archaeological Survey of India, no public gatherings should be organized near them, as was done in the not-so-distant past. Alexander Cunningham, the founding head of the Archaeological Survey of India in his 1871 Four Reports Made During The Years 1862-63-64-65 had mentioned “neglect” of investigation and documentation “for the instruction of future generations” of these caves. Even 77 years after Independence, we haven’t mended our ways.

At the end of our trip to the Caves, as we were about to leave, I caught sight of a blue-and-white rusty Bihar Tourism signboard with road directions. It read Bishnupad Mandir, Gaya, followed by the names of four small towns. As my eyes reached the last entry, I had an epiphany. Kauwa Dol, it read, and immediately I knew we were about to leave E. M. Forster land—the chapter titled ‘Caves’ in A Passage to India had several references to it.

Fact intertwined with fiction.