- HOME

- /

- Culturescape

- /

- Me & My Shelf

- /

Ranjit Hoskote's Top 10 Favourite Reads of all Time

Ranjit Hoskote is an award-winning poet, cultural theorist, translator and curator of more than 50 Indian and global art exhibitions. His poetry collections include Central Time (2014), Jonahwhale (2018) and his latest, Icelight, releasing in June 2023.

picture credit: Priyesha Nair

picture credit: Priyesha Nair

Siddhartha By Hermann Hesse, translated by Hilda Rosner

I first read Hesse’s Siddhartha at 16—a rite of passage for my generation—and fell in love with its ability to bracket the intimate events of its protagonist’s life within the epic scale of quest, loss, ageing, and enlightenment. I re-read it every year, each time discovering a new relevance to its wisdom, which is both melancholy and consoling.

In Praise of Shadows By Jun'ichiro Tanizaki, translated by Edward Seidensticker

Tanizaki’s essay on the expressive power of shadows maps the transition from lamplight to electricity in Japan, and its destruction of subtlety. The Kabuki actor’s shimmering robes, the sheen of lacquer bowls, the glow of the shoji-paper lampshade are all rendered garish by excessive light. I love this moving elegy for elegant forms of life extinguished by a mindless embrace of modernity.

The Wind in the Willows By Kenneth Grahame

First read in childhood, this classic has travelled with me through the decades. Originating in stories that the author made up to amuse his son, The Wind in the Willows—with its perennially vivid characters, Mole, Ratty, Badger, and Mr Toad—embodies, for me, the constant push-pull between home and away, the adrenalin rush of growing up and the solace of circling back, solitude and friendship.

Shame By Salman Rushdie

Having been entranced by Midnight’s Children, I read Rushdie’s Shame in the interval between finishing with school and going to college. I believe it is his finest novel. What a fine evocation of a country modelled on Pakistan, through a mix of legend, folklore, gossip and high-spirited caricature! And its memorable cast of characters, including generals, politicians, agitators and resilient women.

Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood By Oliver Sacks

Scientists and science commentators feature among my favourite prose writers—among them, Oliver Sacks, Gerald Edelman, Stephen Jay Gould, and David Quammen. I find myself replenished by their empathy, their capacity for courage and hope. I return to Sacks often: his reflections from neurological practice, detailing syndromes and pathologies; his travel journal; and this memoir, woven around an eccentric uncle who initiated the boy Oliver into the mysteries of science.

The Craftsman By Richard Sennett

A brilliant sociologist with a keen insight into the interplay of concept and creativity, imagination and technique, Sennett has long been a key point of reference for me. In The Craftsman, he reminds us that we are not driven by abstract hopes of reward alone, but that we are most deeply motivated by possibilities of excellence, achieved in close, visceral connection to the things we make with our hands.

The Hare with Amber Eyes By Edmund De Waal

This expansive memoir revisits the history of the Ephrussi family, to which the author belongs, from their Ukrainian Jewish beginnings and cosmopolitan evolution across Europe, through the horrors of the Holocaust to the present day. The narrative is threaded around a family collection of exquisite Japanese netsuke objects: an inheritance that survives all turbulence, passing from hand to hand, country to country.

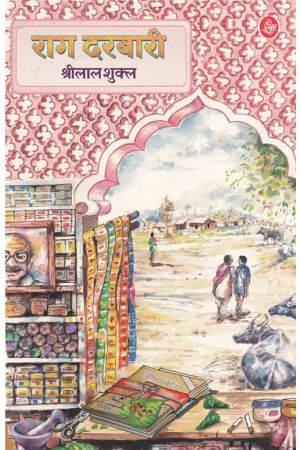

Raag Darbari By Shrilal Shukla

Half a century after it was published, Raag Darbari, which I read in the original Hindi in my early twenties, remains the best guide to the labyrinth of Indian politics from the district level up. With the naïve city-based protagonist, Rangnath, we navigate the power structures and tacit arrangements that sustain the Everytown of Shivpalganj, through a series of adventures ranging from the uproariously comic to the faintly sinister.

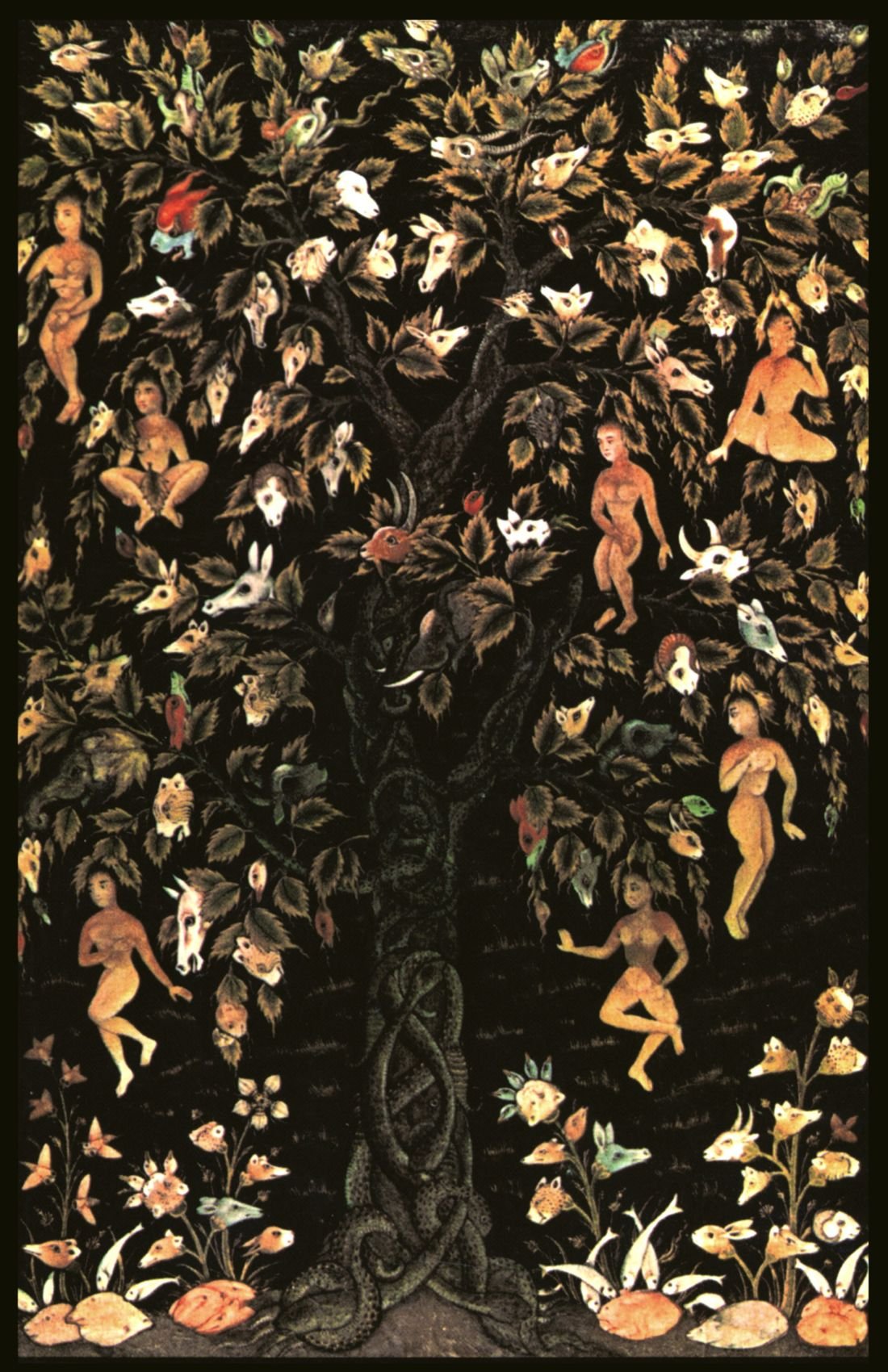

The Speaking Tree By Richard Lannoy

I had the privilege of counting Richard Lannoy as a friend. Over the years, we met, I stayed with him at his rambling home in Bath—its basement dating back to the 17th century, “a house with an Unconscious”—and we wrote to each other often. The Speaking Tree, which has never been out of print since 1971, is—to my mind—the finest guide to India’s complex society and culture, presented through a tapestry formed by the weft of the political and the warp of the aesthetic.

Krishnamurti’s Journal By J. Krishnamurti

Family associations with the Theosophical Society brought me into an awareness of the spiritual teacher J Krishnamurti early in life. I sketched an arc from a youthful rebellion against his influence to a mature acceptance of his compelling insights into humankind’s arrogance in relation to nature. In this journal, which he kept in the early 1970s, he relayed some of his key ideas, woven through with intensely beautiful descriptions of landscapes, seasons, times of day and animals that he loved.