- HOME

- /

- Culturescape

- /

Fiction's Foresight

British-Bangladeshi author Manzu Islam’s works reveal startling parallels to recent political upheavals in Bangladesh, begging the question: Besides helping us make sense of our world, can stories also offer a glimpse into the future?

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

There’s a passage in the British-Bangladeshi author Manzu Islam’s new novel Godzilla and the Songbird (published by Speaking Tiger), where the protagonist, a young journalist called Syed Islam Shah aka ‘Bulbul’, is finding it tough to stay ‘objective’ about the student-led protests mushrooming across his country.

It reads: “If he hadn’t been a journalist, reduced to being a pair of watching eyes, he would have entered the fray. He had been tracking the mood among the students, their restlessness, their gatherings under the banyan. Under its circular canopy, throwing caution into the wind, they were venting their passions for the upcoming insurrection. If freedom demanded blood, they were willing to give it in bucket-loads.”

If you didn’t know the story beforehand, you couldn’t be blamed for thinking this is a prescient description of recent events in Bangladesh. After all, university students played a crucial role in the protests that ultimately led to former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s exit from the country, and the beginnings of a caretaker government led by the Nobel-winning economist Muhammad Yunus.

However, the passage is actually about the summer of 1969, when Bengali nationalism was at its peak and students in (what was then) East Pakistan were protesting widely against the Pakistani government and its premier, General Ayub Khan.

Godzilla and the Songbird follows young Bulbul from the 1940s up until 1971 and the birth of Bangladesh as a nation-state. Born in Calcutta, Bulbul loses his mother in labour and his father during the Partition-related communal violence. His Western-educated Muslim-Leaguer grandfather, Syed Amir Shah and his beloved grandmother (Dadu), flee with the young orphan across the border to East Pakistan. However, discrimination on the basis of caste, religion and accent follows Bulbul and his folks.

Eventually, Bulbul becomes a journalist and witnesses his friends and mentors being split along clear-cut lines: you could either be a part of Bangladesh’s freedom struggle, or you could be seen as a ‘collaborator’ with the marauding West Pakistani armies.

This is comparable to Sheikh Hasina’s real-life, ill-fated ‘razakar’ taunt at student protests a couple of months ago—‘razakar’ was a derogatory term used to refer to those who collaborated with the Pakistani army during 1971.

One of the major themes of the novel is the power and the danger associated with storytelling. Islam uses the quintessential Bengali ‘adda’ as a kind of modern-day version of the Canterbury Tales device: people gathered at an inn or tavern, exchanging stories and gossip. Much of the novel’s midsection proceeds via ‘third-person’ storytelling: minor characters narrating the stories of the principal cast: Bulbul, his grandmother (Dadu), his friends Alam and Sanu, and Deepa Kaiser, the fiery, feminist youth leader he falls for.

See how the corpulent Sanu, known as ‘Sanu the Fat’ in his youth, is introduced in the novel—the language indicates both the classic adda as well as a deity of sorts. Several different Bengali obsessions: food, adda, religious offering (bhog) and of course the pleasure of storytelling, converge here. The boys are offering Sanu their lunches in exchange for his skills as a mime and a storyteller.

“One day, he tiptoed behind the group to see Sanu the Fat sitting on a pile of bricks at its centre. Boys were offering him their lunches ... He sat in deep concentration as if meditating. From time to time he stirred, gobbled up some of the offerings like a snake, and then went back to his meditative pose. Bulbul feared that he would explode like an over-pumped balloon, but he belched, rubbed his nose and began telling a story.”

British-Bangladeshi author Manzu Islam. Photo Photo: courtesy of Manzu Islam

British-Bangladeshi author Manzu Islam. Photo Photo: courtesy of Manzu Islam

There are other manifestations of the importance of (and the threat posed by) storytelling skills: Bulbul’s grandfather (whose own grandfather was a lower-caste Hindu) is shown to have fooled an entire community into believing he had Syed ancestry from the Middle East. Bulbul’s friend Sanu, in the middle of one his tall tales, spins a clearly discernible allegory about General Ayub Khan, and is beaten up for his troubles by a pair of regime loyalists. Godzilla and the Songbird derives its name from the fact that Bulbul (who’s named after a songbird), in his youth, becomes absolutely entranced by the film Godzilla (1954), one of the first non-Bengali movies he comes across.

Islam’s choice of film here is significant: Godzilla, after all, is a creature of toxic nuclear waste, a byproduct of the American obsession with nuclear power, and their nuclear tests in the Pacific Ocean. Young Bulbul, for the first time, realizes that not all stories have clear-cut heroes and villains—he feels bad for Godzilla because he sees the creature as a victim of American imperialism. While Bulbul is going through all of this, there is a strain of anti-American discourse going through East Pakistan as well (“We are turning into Coca-Cola zombies,” a minor character says at one point).

Other than Godzilla and the Songbird, Manzu Islam’s 2011 novel Song of Our Swampland has also seen a resurgence. Together, these two books can teach you a lot about the circumstances of Bangladesh’s beginnings as a nation-state—and how those circumstances are related to recent events in the country. Godzilla and the Songbird is preoccupied with the birth pangs of a nascent nation, as well as the mechanics and aftermath of a revolution—split loyalties, collateral damage, double-crosses and so on. Song of Our Swampland, on the other hand, is a bit of a thought experiment, a Robinson Crusoe-like allegory about setting up a community, a society from scratch. It is especially significant today because of similar, ongoing challenges faced by the caretaker Mohammad Yunus government in Bangladesh: How do we ‘reset’ society into a blank slate? How do we start over without the baggage of the past?

Song of Our Swampland’s protagonist Kamal has been born “with a hole for a mouth”. Other than his sister Moni and the kindly local schoolteacher Abbas Miah, everybody thinks he is the proverbial village idiot. In 1971, as the Pakistani armies are approaching Dhaka rapidly, Kamal finds himself part of a motley crew of survivors aboard a vessel: the actor Ducktor Malek, the village preacher Ala Mullah, a local strongman Bosa Khuni, a pair of boatmen who happen to be Hindu and so on.

Soon, they encounter the ‘Bihari’ woman Kulsum who is a former Pakistani army collaborator—at the time, any migrant from East India was called ‘Bihari’ by the Bangladeshis, and they were viewed with suspicion (because a small group of actual Biharis had indeed worked for the Pakistani authorities).

As you can probably tell by the ethnic makeup of this group, this is Manzu Islam’s ‘petri dish’ scenario, his allegory that asks whether a post-ethnic/post-religion society is possible—or even desirable? In this context, some darkly funny scenes spring to mind immediately. Like the one at the novel’s midway point, when the survivors put on a heavily modified version of the Ramayana as a skit—carefully redesigned “so that the Hindus don’t win at the end” (Ducktor Malek is fearful of communal violence breaking out within the group).

The bare facts of Islam’s life tell you how he arrived at such an astute, clear-eyed assessment of the subcontinent’s collective engagement with religion, politics, displacement and revolution. Born in 1953 in East Pakistan, Islam witnessed the events of 1971 as a teenager. He walked an arduous, swampy route across the India border to reach the refugee camps therein.

Remarkably, he later returned as a freedom fighter. Having moved to the UK years later, he worked as Racial Harassment Officer in the late 1970s and early-to-mid 1980s, the peak of the country’s most openly racist, ‘Paki-bashing’ years. In his novel Burrow, an illegal Bangladeshi immigrant living in the England of the late 1970s reflects on his life thus far—escaping one set of aggressors back home, only to become a hunted man in a foreign land.

Islam hasn’t been interviewed too often, but in 2008 the Bangladeshi newspaper The Daily Star published a Q&A with him. During this conversation the writer spoke about living and working in London’s East End (“the site of our Banglatown”). There were stories about the racism and the violence, yes, but also the hope and resistance displayed by his compatriots. Describing himself as “Bangali-British or British-Bangali”, Islam added that even hyphenate identities are “becoming meaningless” amidst the geopolitical chaos of the 21st century.

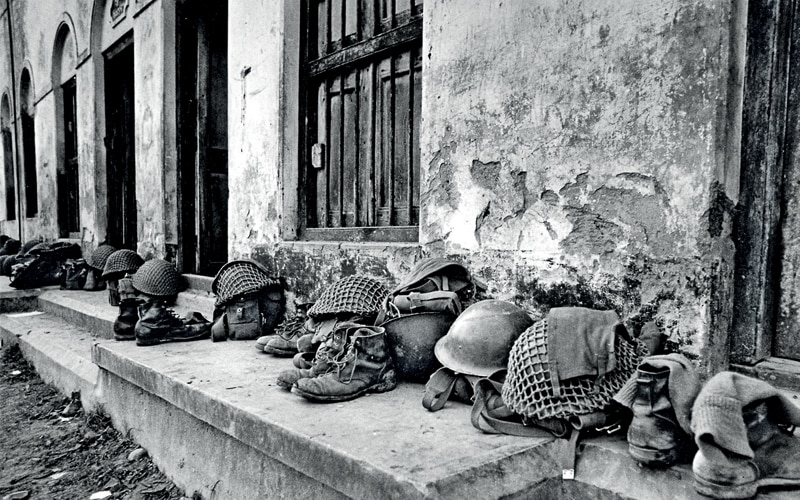

Boots on the ground near Kulna. Mukti Bahini guerrillas, together with the Indian Army only succeeded in taking Kulna a day after Bangladesh attained its freedom on 16 Dec 1971. Photo: Alamy

Boots on the ground near Kulna. Mukti Bahini guerrillas, together with the Indian Army only succeeded in taking Kulna a day after Bangladesh attained its freedom on 16 Dec 1971. Photo: Alamy

“On the one hand, these two events (9/11 and 7/7) gave rise to new forms of racism and Islamophobia, which obviously do not discriminate between those who are secular and those who are not,” Islam said.“I feel it is important to resist these new forms of racism. On the other hand, there is a growing trend among a section of our youth who are seduced by the millennial fantasies of Islamist ideology to take up extreme positions. At present, at the height of an aggressive neo-liberal capitalism, and the corresponding absence of any significant secular, progressive vision of a future, this trend is inevitable because religion seems to provide at least a stage for opposition.”

Even a cursory look at the events unfolding in Bangladesh over the last couple of months reveals how prescient Islam’s fears about “extreme positions” were. Over the last few weeks, Indian newspapers have reported about hundreds of attacks on minorities—Hindus, Christians and so on. Representatives of the Chakma people (recognized as a Scheduled Tribe in several Northeastern states) have staged protests in Delhi and elsewhere. Lakhs of Chakma people live in Bangladesh and in recent times, instances of targeted violence against them have increased sharply.

Recently, Prime Minister Muhammad Yunus as well as several members of his Cabinet have made encouraging statements about punishing the culprits and embracing minorities across the country, but the atmosphere of fear will take time to dissipate. Earlier this month, India Today reported about Yunus’ meeting with the hardliner Hefazat-e-Islam leader Mamunul Haque, and the release of the incarcerated Jashimuddin Rahmani of the Ansarullah Bangla Team (ABT), an al-Qaeda-affiliated terror group. Haque in particular has been noted for his vocal opposition to constitutional values in favor of conservative Islamist stances, especially when it comes to societal norms, women’s education and so on.

Manzu Islam’s books help us understand how Bangladesh has arrived at this point in history. They present a fascinating window into the past and present of a young nation that has witnessed more than its fair share of upheaval. And if his warnings go unheeded by the new power players in Dhaka, these books are also a frightening glimpse into the future that awaits our neighbours.

Essential Reading on Bangladesh

If you're interested in learning more about the country’s politics, history and society, these select books are a must-read:

The Blood Telegram (2013) by Gary J. Bass, Vintage

Arguably the most well-researched and comprehensive non-fiction book about Bangladesh—specifically, how President Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger delivered covert support to Pakistan’s atrocities in 1971. A must-read for newcomers and experts alike.

A Golden Age (2007) by Tahmina Anam, Penguin Books

Tahmina Anam’s 2007 debut novel is still considered one of the finest works of fiction to come out of Bangladesh. The narrative follows determined widow Rehana Haque in the year 1971, as both her children become increasingly involved in the Bangladesh Liberation War.

The Colonel Who Would Not Repent: The Bangladesh War and its Unquiet Legacy (2014) by Salil Tripathi, Aleph Books

How and why was Mujibur Rahman, a central figure in Bangladesh’s struggle for freedom, assassinated? How was the Indian government reacting to the events of 1971? Tripathi’s book of longform journalism seeks to answer intriguing questions like these.

The Black Coat (2013) by Neamat Imam, Hamish Hamilton

A satirical masterpiece and a sign of things to come from Bangladeshi fiction. The book’s main character is Khaleque Biswas, a journalist who hires a village-dwelling young man to impersonate Sheikh Mujibur Rah-man in the early 1970s. But when the lookalike threatens to deviate from the script, tragicomic hijinks ensue.

Banker to the Poor (1999) by Alan Jolis, Muhammad Yunus, PublicAffairs

Now that Muhammad Yunus of Grameen Bank has been appointed the head of Bangladesh’s caretaker government, no time like the present to read Yunus’ micro-finance success story and how his vision helped reduce poverty levels in the country significantly.