- HOME

- /

- Culturescape

- /

- Book Extract

- /

What Can India And Pakistan Learn From Their Relationship In 1950?

The Bengal Pact and the Nehru–Liaquat agreement offer perspectives on the erstwhile India–Pakistan relationship that can be useful even today, when the future of the relations between the two countries is very bleak

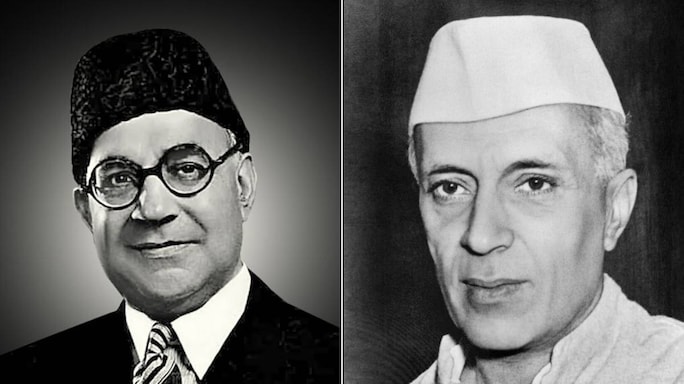

(Left:) Pakistan Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan; (right:) Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

(Left:) Pakistan Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan; (right:) Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

The year 1950, then, was an interesting one: It had all the makings of the sets of causes that bring about both war and peace between India and Pakistan. Nehru and Liaquat Ali Khan had fulminated in their constituent assemblies over each other’s duplicity over the refugee question; but they had also gone ahead with the shaping of a correspondence on the No War Pact. No ‘permanent’ solution—war, peace, or any of the intervening shades in between—was put into place, but a series of ad hoc, interim measures that could be countenanced by both states were devised in the meanwhile to patch things over. What was acknowledged on both sides was that the way to a lasting stability lay in finding answers that could lay the ghosts of partition to rest once and for all. And, to some extent at least, both governments made concerted efforts to bring this about.

At the time of writing, the state of India–Pakistan relations is bleak. Bilateral ties between India and Pakistan have been ‘downgraded’, owing to India’s decision to revoke Article 370 in Kashmir. How, then, are we to evaluate the contributions of the diplomatic infrastructure between India and Pakistan during the 1950s? As we saw in this book, the bilateral machinery opened up interesting spaces for resolving problems in the aftermath of Partition as well as for enabling jointly sought after solutions to be implemented. At the very least, interactions between bureaucrats of India and Pakistan seemed to arrest the pace of the slide towards hostility; at their height—in exercises that are, perhaps, of greater relevance today—they enabled a more proactive and integrated approach to seeking accommodative solutions to questions about a dense set of networks and loyalties that cut across the boundary line.

Indeed, the Bengal Pact would seem to offer several insights that are relevant today. At its heart, after all, the Nehru–Liaquat agreement was a story of how bureaucrats from both states constructed a framework in which diverging and competing claims to multiple nationalities and allegiances that pre-dated the nation state could also be accommodated within a structure that both states put in place, as a means of further bolstering themselves in a jointly coordinated fashion. Obviously, there are many deeply structural differences between the positions of Bengal and that of Kashmir in the framework of the Indian and Pakistan union—which this present work does not claim to overlook. Yet, the extent to which the comparison holds true is also the extent to which bilateral dialogue between India and Pakistan offers the potential for yielding dividends.

The relations between India and Pakistan have been on the decline in recent years. Are there lessons both countries can learn from the past? (Image used for representative purposes only. Courtesy Flickr)

The relations between India and Pakistan have been on the decline in recent years. Are there lessons both countries can learn from the past? (Image used for representative purposes only. Courtesy Flickr)

What also became clear is the deep-seated necessity for the infrastructure of the relationship to stay in place at all: In many ways, the bilateral dialogue was the best instrument for defining the extent of the sovereignty and jurisdiction of both states. Such processes, moreover,tend to align with majoritarian leanings: the experiences of defining the basis of citizenship after partition, for instance, or navigating the maze of rules about evacuee property or even Tyabji’s attempts to further the application of Fazalbhai for trade, also demonstrate the processes that the bilateral framework enabled did not necessarily favour the concerns of minority communities. But a bilateral dialogue,based on the agenda for finalizing the partition—and therefore on the recognition of the basis of both states’ existence—could also lead to outcomes that temper and accommodate these questions into a more fruitful result. A stronger diplomatic dialogue with Pakistan,moreover, also enabled the welfare of the minority populations of the subcontinent to become part of the government’s agenda at a more structurally integrated level, than that of simply voicing optimistic intentions about the well-being of minorities.

Obviously, the story of India–Pakistan relations is also one of the process of state-finishing, and the consolidation of ‘cartographically anxious’ states. Itty Abraham, for example demonstrates how India’s emphasis on its territorial integrity also stems from an anxiety about the lack of any other unifying principle. In terms of language, or religion or ethnicity or even a fool-proof basis of claims to citizenship on the basis of being born on the same soil, the Indian union offers no unifying, cohesive principle for a diverse population. The anxiety about making the state territorially cohere, therefore, produces an unusual degree of emphasis on the integrity of its boundary lines—at the cost of its relations with its neighbours. South Asia is also witness to the development of states that are still chasing the nation. Of states, in other words, that are still varnishing the idea of the national community—who is to be in it, who is to be excluded, and which sets of people’s historical imaginations are to be given the most salience to. Such questions continue to deeply affect how the terms of the bilateral relationship have been framed.

The gaps between reconciling these two ideals—of shaping a ‘strong state’, territorially defined, and certain of the basis of the community it is in existence for, on the one hand, and the still incomplete process of determining who and what exactly is to be within these states on the other—is also in a sense responsible for the differences and inadequacies of the India–Pakistan relationship. Such debates were clearly in existence during the 1950s as well, and to a greater extent, and both states were able to address with a greater degree of circumspection and prudence. Yet, while it has also been argued that the decades prior to the 1965 war were easier on Indo–Pakistan relations, partly because of the continuance of cross-border, inter-personal contacts of an earlier generation, I would also argue that the differences between that decade and this also need to be viewed from the point of view of the declining power of the state as a whole: The 1950s, in fact, witnessed the height of the sense of possibility in the capacity of the state, and the capabilities, responsibilities and accommodativeness of its institutions.

Book cover courtesy HarperCollins India

Book cover courtesy HarperCollins India

In a sense, however, the argument that the 1950s were a period of hectic cooperation and dialogue has a deeper significance: This generation, after all, had witnessed the very worst of the traumas that subcontinental politics could have thrown at them. The numbers of casualties arising out of the partition, and the ensuing ethnic genocide, quite easily dwarf the scale of violence seen in the more recent instances of violence between India and Pakistan. If, in these conditions, policy makers of India and Pakistan could conclude that the best remedy for the situation called for a series of detailed negotiations about how to put to rest the lingering questions arising out of the partition, these arguments can also serve as a relevant guide to the maze of India–Pakistan relations today.