- HOME

- /

- Better Living

- /

- Mind

- /

In Praise Of Guilty Pleasures

Go ahead and binge-watch some more reality TV. Our ‘lowbrow’ indulgences aren’t so bad for us after all

Photos: Maor Winetrob/Getty Images (TV). inset images Clockwise from top left: hgtv, Virginia Sherwood/NBC, food network, Newsday LLC/Getty Images, Maarten de Boer/abc

Photos: Maor Winetrob/Getty Images (TV). inset images Clockwise from top left: hgtv, Virginia Sherwood/NBC, food network, Newsday LLC/Getty Images, Maarten de Boer/abc

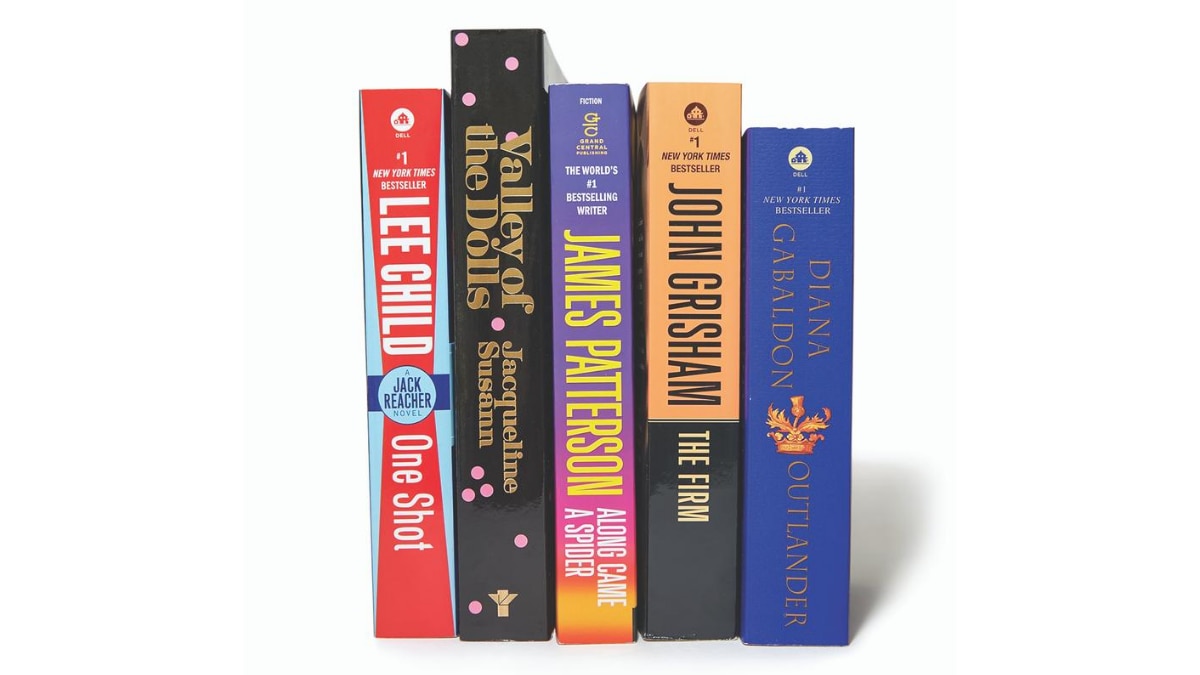

We all have them: TV shows and movies we love, even though we just know they’re bad. Trashy books we simply can’t put down. Awful earworms we hate to love.

These are our guilty pleasures—what you might call the junk food in our media diets. Because it’s often used in a winking way, the term guilty pleasure feels like a joke we’re proving we’re in on. But if that joke is about something that brings us genuine joy and isn’t harming anyone, then what’s the punchline? Shouldn’t we be free to enjoy whatever we like?

“A guilty pleasure is something that we enjoy, but we know we’re either not supposed to like or that liking it says something negative about us,” says Sami Schalk, PhD, an associate professor of gender and women’s studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, USA. Consider what separates some major TV events from others. The idea of apologizing for watching the Oscars or the IPL finals sounds silly. So why is the Bigg Boss finale different?

Research shows that our so-called guilty pleasures can actually be good for us. So how do we get to the point where we let ourselves enjoy what we enjoy?

Beyond the fear about how others will perceive us, we tend to grapple with a perfectionism that stems from the “deeply puritanical roots” of our culture, one in which pleasure is seen “as sinful and bad and self-indulgent,” says Schalk.

Or, at the very least, we have to earn it. How often do we say things to ourselves such as, I’ve been good all week, so I deserve some ice cream or I walked this morning, so I’m going to veg out tonight? But all this guilt goes against our human nature.

“There’s a reason why our bodies, literally at the nerve level, are wired to feel pleasure,” says Adrienne Maree Brown, author of Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good. For her, pleasure activism—spreading the message that we deserve to enjoy ourselves—is about combating the oppressive idea that pleasure isn’t a natural part of life or that only certain people deserve to enjoy themselves.

She suggests asking, “Why do I feel so much shame around this, if it’s not causing harm to me or anyone else?”

After all, binge-watching seven episodes of Real Housewives or ‘wasting’ the afternoon watching back-to-back classic football games isn’t going to melt our brains. In fact, studies suggest that “playing a video game or watching a movie or television show can restore some psychological resources,” says Robin Nabi, PhD, a professor of communication at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who specializes in the effects of media on emotions.

Though the benefits have yet to be studied long-term and our problems don’t magically disappear once we turn off the tube, rest can reduce stress levels. Perhaps more important, Nabi says, “your perception of your ability to handle it improves.” Giving ourselves permission to enjoy some downtime is also a key part of self-compassion, which helps combat anxiety and depression.

“When we rest, we think we’re supposed to use that time productively,” says Kristin Neff, PhD, an associate professor in the department of educational psychology at the University of Texas at Austin. While that “may be good for survival,” she points out, constantly running through hypothetical problems “is not very good for happiness.”

Photo: Joleen Zubek

Photo: Joleen Zubek

Taking a mental break and enjoying something that doesn’t require intense intellectual focus gets us out of problem-solving mode, says Nabi. That is healthy for us on many levels. ‘Flow states’, such as meditating, playing sports and, yes, consuming media, can help our brains rest and recover by providing a reprieve from problem-solving mode. Such breaks can also improve our ability to deal with stress and recharge our batteries, so to speak.

“We have this cultural value of media consumption being edifying, and that what we do should be about growing and achieving,” says Nabi. “We don’t focus as much on relaxation and playing and enjoyment and fun, and these are such important aspects of being a human being.” And feeling guilty about activities we enjoy, or disparaging them, can detract from the benefits they offer us.

For one thing, if we stigmatize a behaviour and then engage in it, it’s easy to go overboard, which can leave us feeling guilty and less satisfied. In one study, dieters who had been coached in self-compassion were less likely to overeat after consuming unhealthy food, while those who simply followed restrictive diets were harsher on themselves.

While guilt can sometimes be a healthy motivator to push us to change behaviours we don’t like, its counterpart, shame—the painful feeling that our behaviour makes us horrible people—is never productive. When we disparage our TV-viewing habits, for example, we typically aren’t describing a behaviour we hope to change, so the negative feelings aren’t particularly productive or helpful.

Brown reminds us that it’s normal and even healthy to embrace our need for pleasure. She adds one caveat, though: a reminder that too much of a good thing is never a good thing—which is why understanding and accepting what brings us pleasure is crucial to finding the right balance. Shedding our self-imposed embarrassment about our interests can be empowering, which is why it’s time to ditch the term guilty pleasure from our collective vocabulary.

One big reason to do so is that talking about our common interests and pursuits, whatever they may be, is a way to connect with others. The most important value of a guilty pleasure might just be the bond it can create between people who share it. You’ll never find those connections if you don’t speak up. So stop apologizing. Talk about your pastimes. You might just find that it alleviates any residual guilt and makes it easier to discover more things you enjoy.

“Lots of the time, guilty pleasures get talked about in terms of genre,” says Schalk. But it can help to think about what you like specifically, she points out. “You probably don’t like all boy bands, so what is it about this particular group and their music? Whatever it is, find your little niche and go for that. And don’t be ashamed of what that is, because clearly it’s doing something for you.”